Trail starts at Elizabeth Fort Museum, Barrack Street.

Introduction:

In its day the walled town of Cork would have dominated the swampy estuary of the River Lee. Imagine an eight to ten-metre high and two-metre-wide rubble wall of limestone and sandstone, creeking drawbridges, mud filled main streets and laneways, as well as timber and stone built dwellings complete with falling roof straw and a smokey atmosphere from lit house fires keeping out the damp.

Today the walls are long gone for the most part but one can still re-discover several of the old laneways and later incarnations of structures marking medieval churches, tower houses and drawbridges and the maritime portcullis.

Below is a brief historical walking trail, which covers some of the topics on my physical walking tour.

Context & George Carew’s Map of Cork:

Plantation President George Carew’s impact on the cultural and political landscape of Munster was vast. By the spring of 1586 Carew had been knighted and was sent on a private mission by Elizabeth I to Ireland. Carew arrived into a country where huge tracts of the Earl of Desmond’s lands in Munster had taken over by the English crown. About 300,000 acres of land were confiscated in total. From 1585, the plantation of Munster had began and new English settlers were given land. As a reward to Carew’s loyalty, he acquired large estates.

Carew’s rise in political circles and in English power structures in Ireland was quick. In February 1588 Carew was appointed Master of the Ordnance, and returned to Ireland. In 1590 he was admitted to the Privy Council. Two years later in 1592 he was made Lieutenant-General of the English Ordnance, and in 1596 and 1597 he was engaged with Essex and Raleigh in expeditions against Spain.

In March 1599 Carew was appointed to attend the Earl of Essex to Ireland and on 27 January 1600 he was made President of Munster. Carew’s proceedings for the next three years during his term as President are carefully detailed in Pacata Hibernia (1633), nominally written by Thomas Stafford, but inspired by himself.

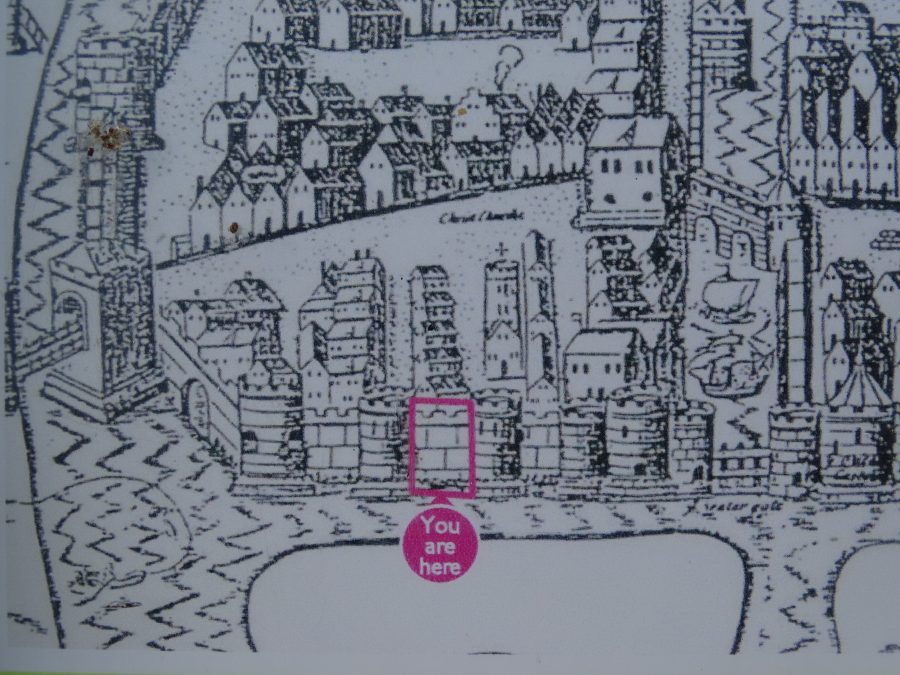

Carew’s Pacata Hibernia Map:

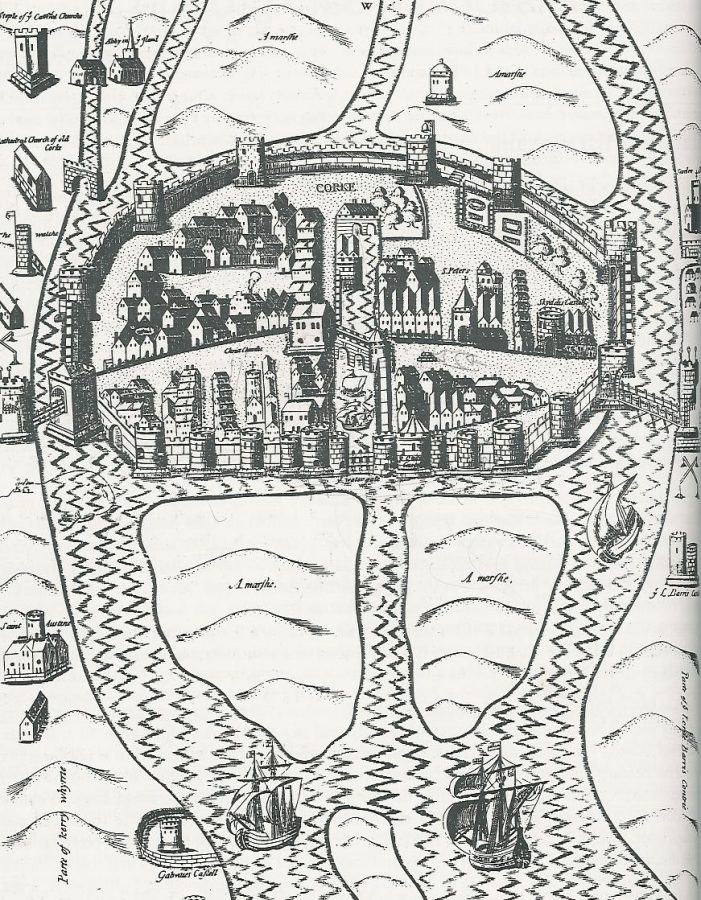

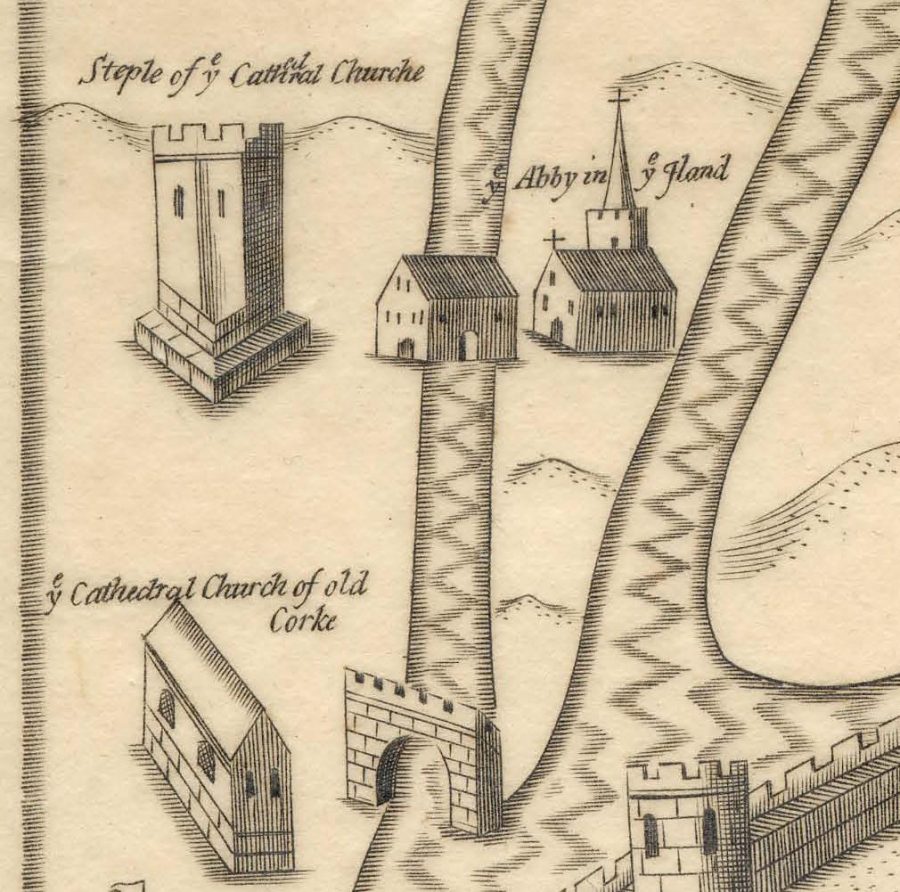

Within Pacata Hibernia is George Carew’s commissioned and iconic map or sketch of the Walled Town of Cork. It is dated to the late sixteenth century – sometime in the 1590s perhaps. The map depicts numerous structures, which emphasise Cork as a port and a place to be protected as an English outpost of trade. The town walls, the Tudor ships, and the suburban features such as abbeys and watch towers show a town prepared for any potential attack and the difficulties of an attack.

The river is presented as an integral feature around which the plan is defined. it is an English-made map to control territory. Here a militarised maritime zone is depicted.

This history trail is based on Carew’s first map of Cork and some of the core spaces, which once existed.

Carew’s Second Map of the Walled Town of Cork:

It is also worth nodding to George Carew second map of the Walled Town of Cork, which was created shortly after the creation of the first. This colourful Plan of Cork c.1600 is based in the Hardiman Collection in Trinity College Dublin places an emphasis on an ordered walled town on a swamp complete with houses, laneways, drawbridges.

In this plan the emphasis is less on the height of the walls and more on the roads leading into the settlement. It shows a new dock area to the east to accommodate increased trade. But it is the showcasing of Elizabeth Fort (with the Holy Rood Church within), which is perhaps why this map might have been created.

VIEW George Carew’s second commissioned map of the walled town of Cork, which is held in the Hardiman Collection at Trinity College Dublin.| A description of the Cittie of Cork, with the places next adjacent thereto | ID: p2676w00t | Digital Collections (tcd.ie)

Elizabeth Fort:

Due to the stand-off in the Battle of Kinsale between English and Irish and Spanish, a reference in State Papers from late 1601, which details Carew paid 200 labourers to expand an extensive trench in the southern suburbs of the walled town, and that the project was paid by the walled town and the English administration in Ireland. A further reference in the State Papers from Carew to Lord Mountjoy on 6 August 1602 reveals Carew’s interest in creating the large earthwork, which was to become Elizabeth Fort;

“That irregular work your Lordship saw at the south end of Corke, first intended for no other end than a poor entrenchment, for a retreat, is now raised to a great height equal or above all the grounds about it, and so reinforced with a strong rampart, as a powerful enemy shall not carry it in haste, and whilst that work holds out it shall be impossible for an enemy to lodge near that end of the town. The work is great, the Queens charge in erecting it nothing”.

References in the same Carew papers also mention the construction of a new fort at Kinsale (in time to become James Fort) and a fort on Haulbowline Island in Cork harbour.

VIEW Elizabeth Fort with Kieran’s short film:

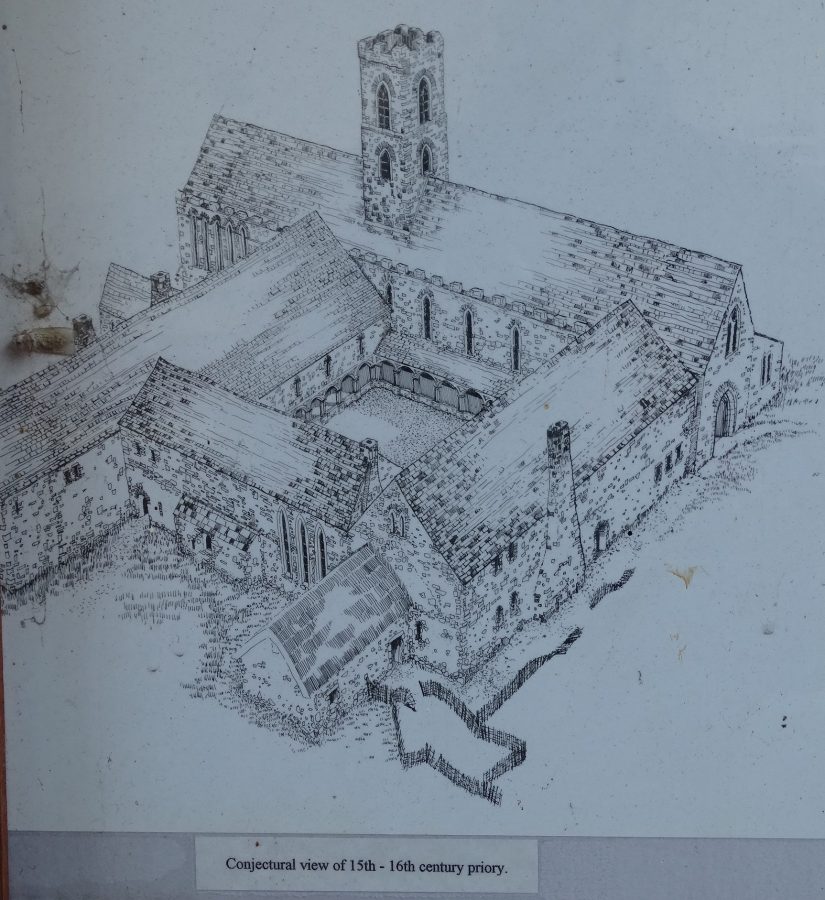

The Dominican Abbey & Crosses Green:

George Carew’s Pacata Hibernia map shows the Dominican Abbey on a marshy island to the south-west of the walled town. The map illustrates a church with a large steeple with an adjacent water mill built next to the river.

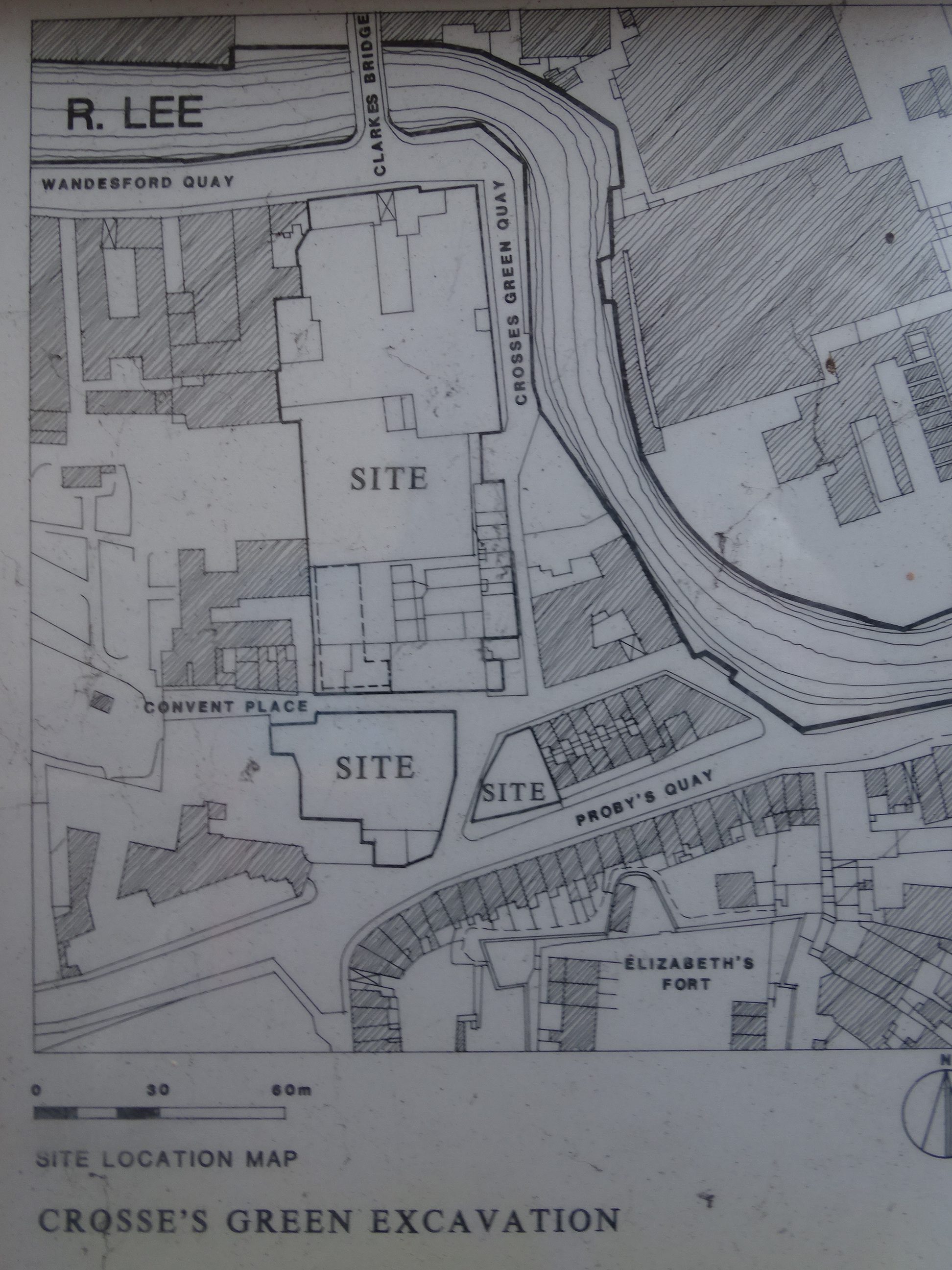

The name of the island was Sancta Maria de Insula or St. Marie’s of the Isle, the area of present day Crosses Green. This marshy island like the islands on which the adjacent walled town was built on, would have been subject to constant flooding at high tide. When the abbey was being built, the unfavourable local ground conditions would have been taken into account.

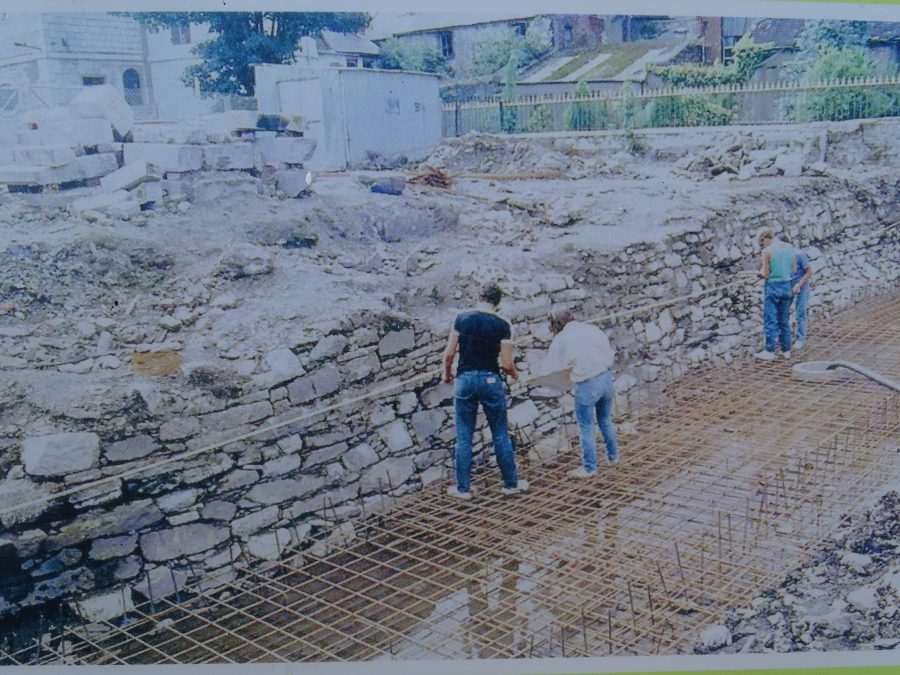

Exciting finds were unearthed in 1993 during the placing of foundations for the Crosses Green Apartment Complex. Excavated remains of buildings were discovered associated with the abbey especially the church, cloister or central walking area. A total of two hundred graves were found. Under the careful excavation of Catyrn Power, three-quarters of the individual skeletons were found to be adults – the largest number being aged in their twenties. The mortality rate was found to be low and through present day research on medieval times, numerous reasons have for this have come to the forefront such as diet and living standards of the time.

READ an Evening Echo Article on the archaeological excavation at Crosses Green:

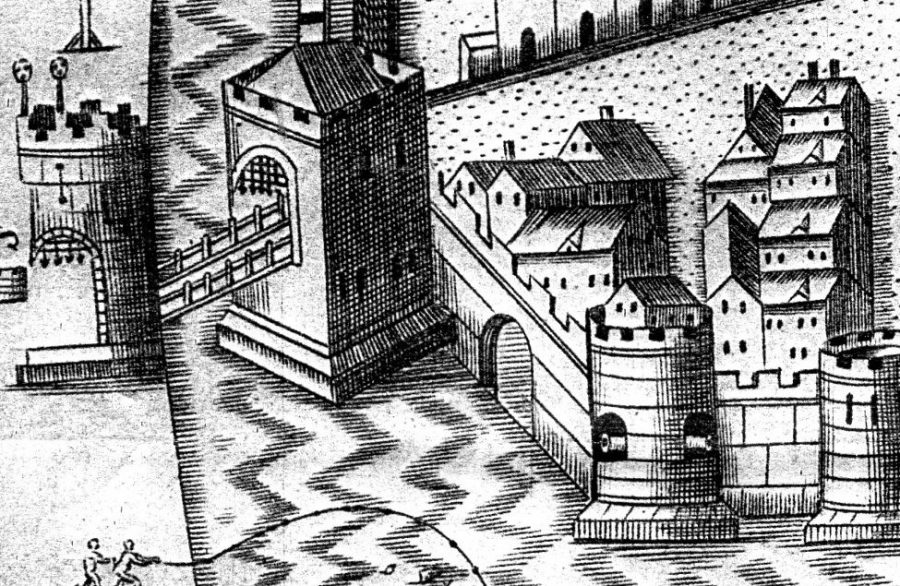

South Gate Bridge:

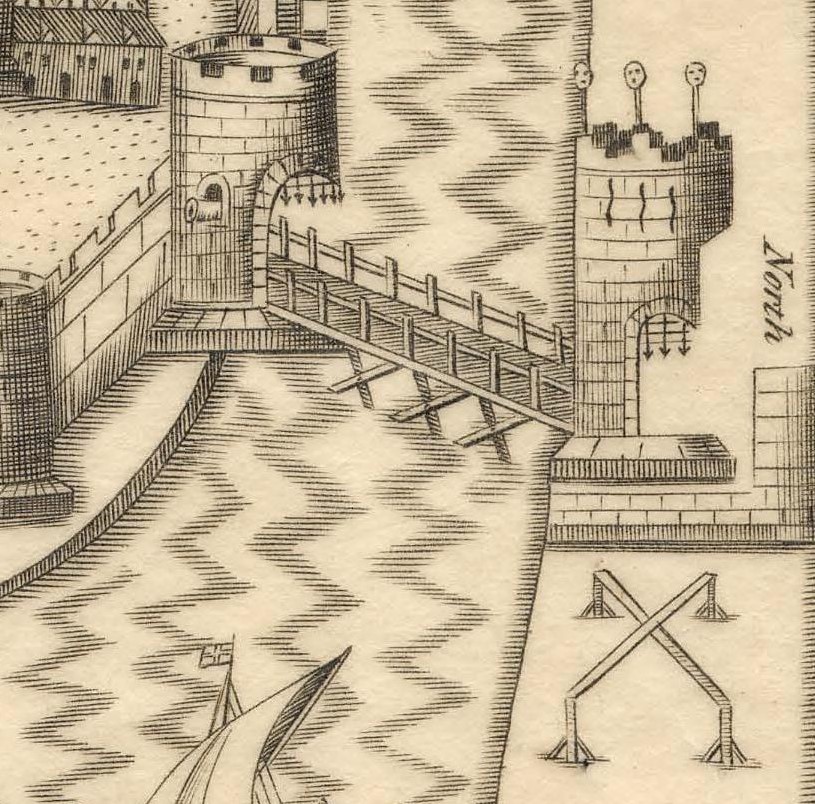

In the time of the Anglo Normans establishing a fortified walled settlement and a trading centre in Cork around 1200 A.D., South Gate Drawbridge formed one of the three entrances – North Gate Bridge and Watergate being the others. South Gate Drawbridge was a wooden structure and was annually subjected to severe winter flooding, being almost destroyed in each instance.

A document for the year 1620 stated that the mayor, Sheriff and commonality of Cork, commissioned Alderman Dominic Roche to erect two new drawbridges in the city over the river where timber bridges existed at the South Gate Bridge and the other at North Gate. South Gate Bridge became known as Roche’s Bridge after its commissioner.

In May 1711, agreement was reached by the council of the City that North Gate Bridge would be rebuilt in stone in 1712 while in 1713, South Gate Bridge would be replaced with a stone arched structures. Both North and South Gate Drawbridges were designed and built by a George Coltsman, a Cork City stone mason/ architect.

South Gate Bridge still stands today in its past form as it did over 300 years ago apart from a small bit of restructuring and strengthening in early 1994.

Various depictions of the walled town such as George Carew’s map in the late sixteenth century show menacing symbols of power at the top of the drawbridge towers, where the heads of executed criminals were placed as a warning to other citizens. The heads was placed on spikes, which were slotted into a rectangular slab of stone.

Legend has it that one of the stone blocks still exists today at the top of the steps of the Counting House in Beamish and Crawford Brewery on South Main Street.

Town Wall Find at Grand Parade City Car Park, South Main Street:

Initially created by the Anglo-Normans, c.1180 AD, the town walls were extended and rebuilt by further English colonialists through subsequent centuries up to the Siege of Cork in 1690. Cork was one of 58 walled towns in Ireland.

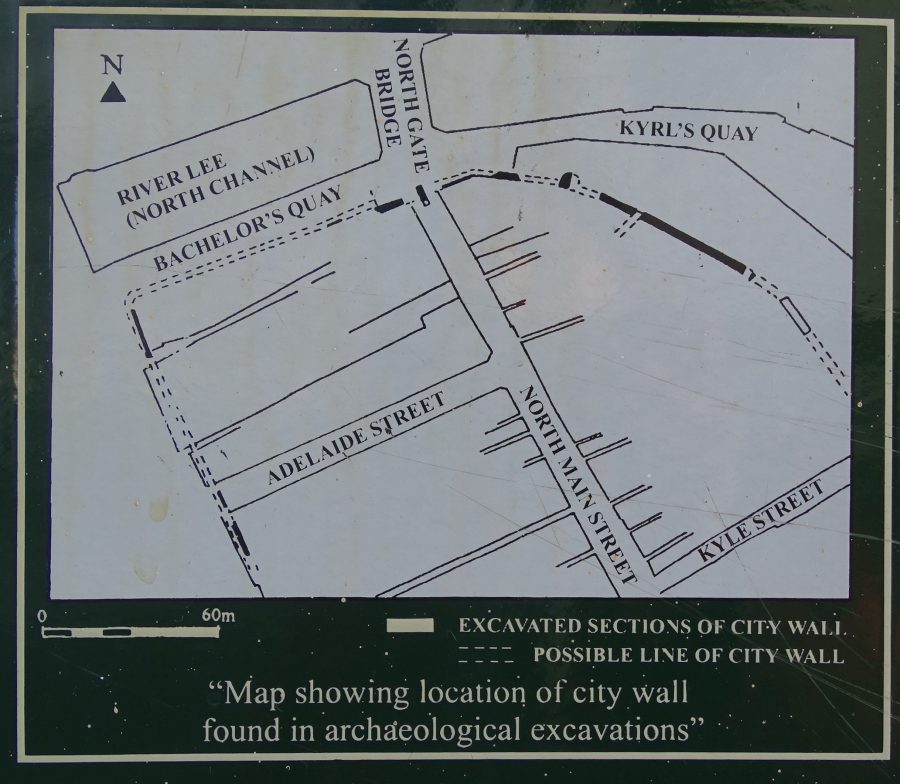

In general, much of the town wall survives beneath the modern street surface of the city and in some places has been incorporated into the foundations of existing buildings in particular buildings overlooking the Grand Parade.

The type of stone used for the construction of the wall consisted of limestone and sandstone, both quarried in local contexts. The stone was cut into irregular shaped blocks. Mortar has also been found between these blocks and an analysis of this has revealed that it was comprised of crushed egg-shells, charcoal, mixed in with gritty lime mortar, which held the blocks together!

In 2003 and 2004, part of the town wall was uncovered in the Grand Parade City Car Park. On behalf of Messrs Kenny Homes Ltd, the excavations were directed by Maire Ní Loinsigh and Deborah Sutton of Sheila lane & Associates. This section of the town wall was part of the southern circuit of the enclosing medieval wall of Cork and on George Carew’s Map of Cork it shows a large entrance (maybe a quayside?) of some kind embedded in it.

The subsequent published archaeological report recorded that a total of 50.3m. of the town wall in length was discovered, and this ran parallel to the existing riverside wall.

In parts the wall was only 1m wide and it rarely exceeded 1.5m in width. The wall was construction was constructed on a a timber raft foundation on which the wall was erected.

The town wall was built of mortared stone on a “single course of offset sandstone foundation slabs”.

The archaeologists discovered intentional dumping of waste to the north of the city wall artificially raising the ground level. This was pursued to enable the building of the upper levels of the wall. Several rebuildings of the town wall were recorded.

The Municipal Heart, Former Beamish and Crawford Site:

The population of Cork c.1300 is estimated at 800 people with the main language of the law being English. It is likely that wealthy Anglo-Norman families of the merchant class were the principal residents as they would have been able to afford the rents payable to the King. Some of these wealthy merchants founded the Corporation of Cork, a municipal, legal, and administrative body; it is unknown when it was formed or how many members it had.

The Corporation controlled the town’s financial affairs and aimed to create a vibrant mercantile economy in the town, ensuring that all associated taxes were paid. It was also responsible for upholding the laws of the town and paying a watchman to supervise after the towns’ defences and streets.

Much of the corporation’s public business was conducted just off South Main Street, in the area now occupied by Beamish and Crawford Brewery. The council tower, armoury, the court house, commandant’s house and the treasury were all located nearby.

A merchant’s hall was present in this area, now occupied by the site of Beamish and Crawford Brewery on South Main Street. It provided a place where traders could meet, bargain, set prices and discuss local and European trading news.

READ “Digging into the past reveals Cork settled much earlier than thought”, Irish Examiner, 29 January 2018 by Niall Murray in an interview with Dr Maurice Hurley: Digging into the past reveals Cork settled much earlier than thought (irishexaminer.com)

South Main Street:

The families involved in the government of the town included the Roches, Skiddys, Galways, Coppingers, Meades, Goulds, Tirrys, Sarfields, and the Morroghs. These surnames comprised the mayoral list from the early thirteenth century until the seventeenth century: forty mayoral titles in the Galway name are recorded between 1430 and 1632; thirty-six Skiddys between 1364 and 1624; and twenty-nine Goulds. These families also controlled large portions of Cork’s trade and owned land which they rented out to less fortunate merchants. From the fourteenth century to the sixteenth century, the majority of the houses overlooked the main streets.

Extending perpendicular to North and South Main Streets were numerous narrow laneways, which provided access to the burgage plots of the dwellings. Comprised of individual and equal units of property, burgage plots extended from the main street to the town wall and their size was carefully regulated by owners and tenants.

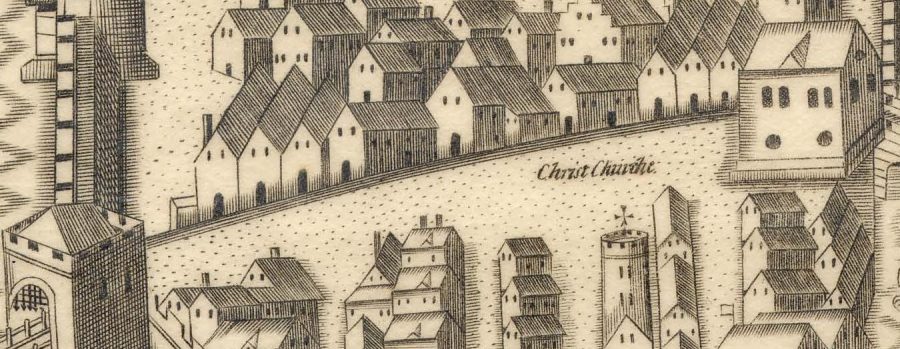

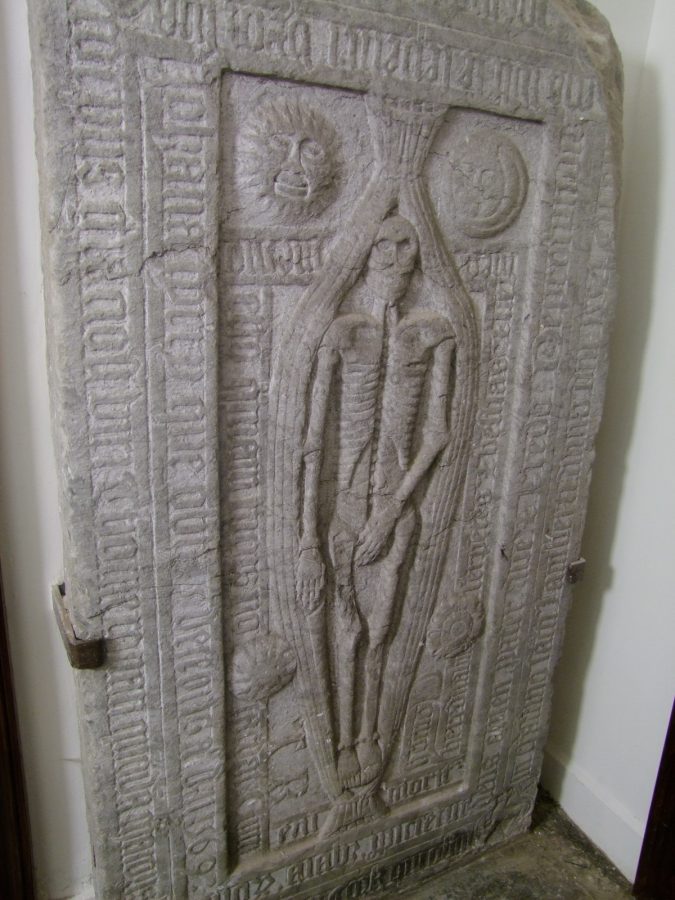

Christ Church & The Modest Man:

Christ Church, now the Triskel Christ Church Arts Centre, presently standing is reputed to be the third on the site. The first one was Danish and the second building was Anglo – Norman. In the twelfth century, the Normans came and took possession of Cork in 1177 and in 1180, Christ Church was rebuilt as a stone structure on the same site as the first. The second church comprised a tower, a steeple, a peal of bells and thick walls. Encompassing the church was a college, alms house, gardens and houses for the priests.

A chapel in praise of the crusades was built in 1310. An organ was given by Sir Francis Drake to the church, which he took from a Spanish Galleon, circa 1588. During the Siege of Cork in 1690, supporters of James II took over the walled city captured some Protestants inhabitants and shut them in the tower of Christ Church. Christ Church was badly damaged by a cannon ball in the siege, which landed on the roof and destroyed it.

The third church was built and the first Sermon preached from the pulpit in the centre of the new church by a Rev. Philip Townsend on 20 November 1720. The church was rebuilt by George Coltsman, who also designed the eighteenth century South Gate and North Gate Bridges and their associated gaolhouses. Disaster struck in the new western tower when the foundation of the tower sank, thus making the tower lean. Over the centuries, various renovations have been carried out to reduce the slope of the leaning tower. Check out former mayor of Cork Thomas Ronan’s Modest Man tombstone and the crypt beneath the church.

WATCH a brief history of Triskel ChristChurch:

800 Years & Bishop Lucey Park:

In 1984 / 1985, Bishop Lucey Park was created to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the granting of the first charter by King Henry II to the citizens of the walled town of Cork. Ironically, whilst preparing the ground for the park, a section of the imposing town wall was exposed, excavated and was added to the park.

WATCH a short news piece from an RTÉ News report broadcast on 10 June 1985. The reporter is Tom MacSweeney and features footage of the town wall find at Bishop Lucey Park. Click here: RTÉ Archives | Environment | Cork Heritage (rte.ie)

An Upturned Canon:

In September 1690 a Jacobite army along with a number of Irish rebel factions combined forces to take control of Cork to provide a stronghold position against King William. The actual number of insurgents is not recorded, but it is likely that several hundred soldiers were involved in the takeover of the walled town. These forces were welcomed by the Catholics in the area. They manned the drawbridges and the town wall-walks, readied numerous buildings and waited for the attack they knew must surely come.

In September 1690, King William despatched the Earl of Marlborough, and a large contingent of men to regain control of Cork. On Monday, 22 September 1690, Marlborough arrived in Cork Harbour with over eighty ships and approximately five thousand men. Marlborough decided that he could exploit the main defensive disadvantage of the walled area: its low-lying position overlooked by hills. Control of the hills would mean control of the walled town.

On Saturday, 27 September, the bombardment of the city escalated. The cannons concentrated on breaching the eastern wall, a point now marked by the City Library on the Grand Parade. After a few more days of sustained attack, the rebels within the walled town surrendered. The principal rebel leaders were transported to the Tower of London.

Today, two interesting remnants of the Siege can be seen in the city. On the corner of Grand Parade and Tuckey Street, embedded into the pavement, is a cannon that was reputedly used in the battle; it is thought that it was later used as a mooring post for a quayside in the 1700s. The second is a cannon ball fired from Elizabeth Fort at the tower of St FinBarre’s Cathedral. During the rebuilding of the cathedral in 1735-1738, this twenty-four-pound cannon ball was found embedded in the spire, about ten metres from the ground. It is on display in the ambulatory of the present cathedral. The siege proved to be a major catalyst in initiating change in the physical and social landscape of the walled town.

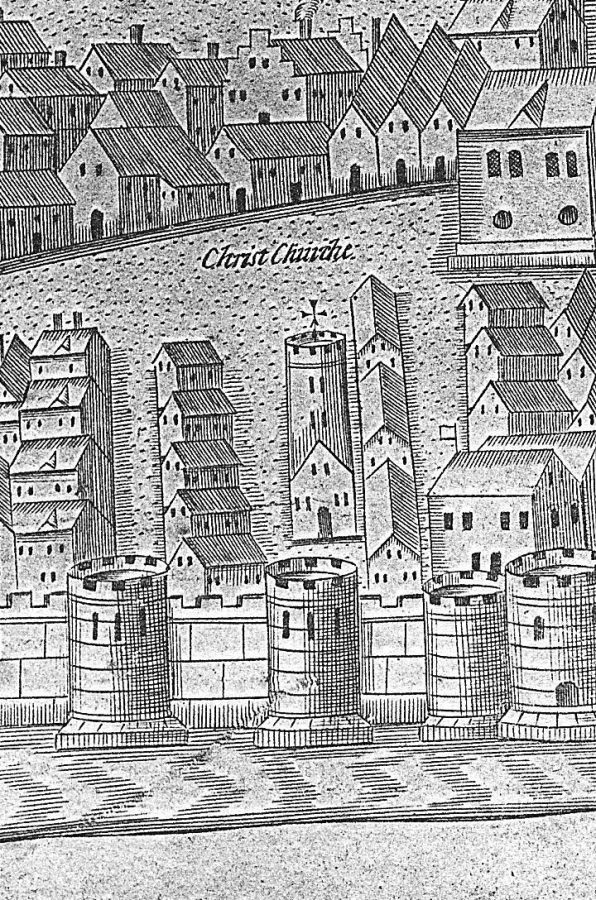

The Watergate:

The Watergate complex, comprising Cork’s medieval port, docks and custom house, would have been impressive. The gate allowed controlled access into a private world of merchants and citizens – the masts of ships, vessels filled with goods and people, creaking as their wooden hulls knocked against the stone quays.

Everyday there was a hive of activity at the quays of the town, especially with the arrival of ships from abroad. All ships docking at the quay inside the town had to report their goods to the custom house, which was adjacent to the quays. No remains of this custom house exist today, but the site is now marked by the Catholic Young Men’s Society at the intersection of South Main Street and Castle Street or Exchange, which would have overlooked the interior dock. Here, taxes were paid on all goods being imported and exported.

The Watergate entrance was between the two castles – King’s Castle and Queen’s Castle. Both castles are signified in the city’s coat of arms with a ship travelling from one tower to another and the latin inscription, Statio Bene Fida Carinis, which means A Safe Harbour for Ships.

In the view of the English Crown, the walled town of Cork was an important strategic point to hold. The settlement lay adjacent to a large, deep and sheltered harbour with easy access to a rich agricultural hinterland, which meant that a substantial profit could be made through the export of produce.

In the late thirteenth century, Cork had seventeen per cent of all Irish trade and was the third most important port in Ireland after New Ross and Waterford. The long list of exported commodities comprised oats, wheat, beef, pork, oatmeal, fish, butter, cheese, tallow (a form of animal fat) and malt. Hides, skins and wool were also exported. The principle hides sold being from cattle, horse, deer and goat. The various skins came from small wild animals such as rabbit, fox, marten and squirrel.

Exports from Cork during this period were sent to Bordeaux, Normandy and Dieppe in France and to Newport, Plymouth and Dartmouth in England. Trading was also conducted between Cork and Bristol, Chichester, Minehead, Southampton and Portsmouth. These also became import destinations.

In 1996, when new sewage pipes were being laid on Castle Street, archaeologists found two portions of rubble that indicated the site of the rectangular foundations of Queen’s Castle. A further section was discovered in 1997. During these excavations, sections of the medieval quay wall were also recovered on Castle Street.

Former site of Queen’s Castle on the right marked by the directional sign and Watergate to the left, present day (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

Watch An RTÉ News report broadcast on 11 December 1992 by reporter Tom MacSweeney on archaeological excavations in Cork in 1992 an a subsequent exhibition at Cork Public Museum, click here: RTÉ Archives | Environment | Cork City Artefacts

Paradise Place, North Main Street:

In the sixteenth-century walled town of Cork the centre of the settlement was known as Middle Bridge with the adjacent castle site known as Paradise Place. George Carew depicts a castle at the head of a canal, which flowed by the present Castle Street. It does not have a detailed history other than that it was built by one of the Anglo Norman descendants of the Roche family. The castle is referred to in records by several names – The Parentis, The Golden Castle,

The architectural term Paradise means a stone parapet in front of a public building and also applies to spaces adjoining. Reputed to be a circular tower, the castle was used as a mint in the reign of King John. It continued to have that function during the reign of Edward the Fourth, when it was known as Dundory, the fort of gold, or the Golden Castle. Down to c.1910 a rent was paid to the Corporation of Cork, whereby at that time the Roche line was broken and the Corporation took over the site.

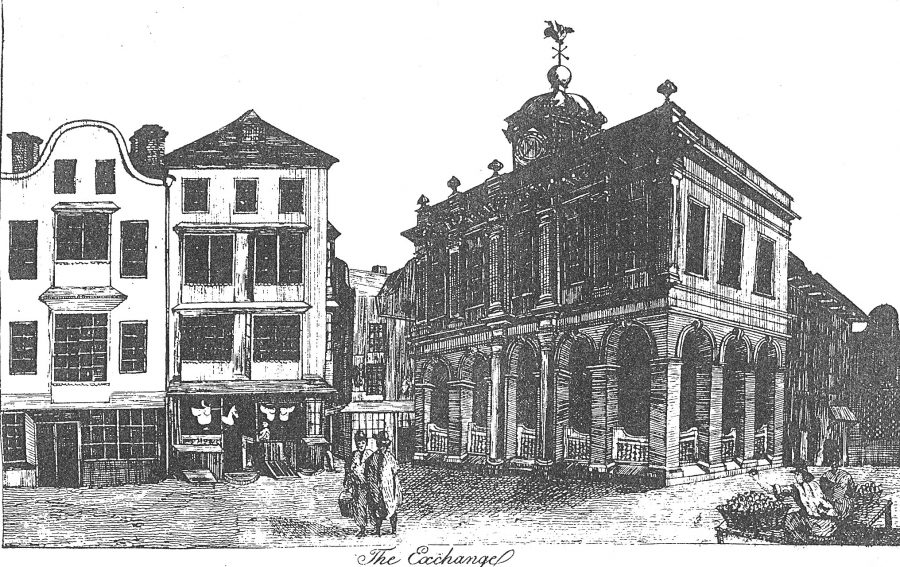

The Tholsel:

The elegant Exchange or Tholsel was built on the site of Roches Castle. It was an important building of two stories. On its opening in 1710 the Council ordered the upper floor room be established as a Council Chamber with liberty for the Grand Jury of magistrates and landlords to sit. The lower part was used for commercial purposes. where a pedestal known as “the nail”, was used for making payments (still in existence in Cork City Museum). In later times the room was used for public sales.

A figure of a dragon made of copper and gilt surmounted the cupola of the building as a weather vane. It was presented to the Royal Cork Institution in 1836, and removed on two occasions, but recovered first with the loss of the tail and later without the head. It was finally disposed of in 1865.

The Exchange declined as a market in time – through the erection of a Corn Market on the Potato Quay (popularly known as the Coal Quay) and improved facilities for the transaction of business offered to merchants. The building, however, continued in use as an Assembly Room and Auction Mart, with part of the premises let for shops and printing offices. Some adjoining houses, the first erected in the city under the Tontine system by a Mutual Building Society, were also occupied by stationers and kindred traders, a circumstance which tempted Corkmen—never at a loss for a nickname—to bestow on Castle Street the sub-title, Booksellers’ Bow. The People’s Hall was eventually occupied by the Catholic Young Men’s Society and today awaits a new community group to utilise it.

North Main Street:

George Carew’s depiction of 1601 shows North Main Street, which is fronted by three-storey buildings. Laneways are shown extending at right angles from the main streets, eastwards and westwards. Additional buildings are shown, both dwellings and outhouses, and these were constructed well back from the main streets. They are located in the original plots of the Anglo-Norman houses and aligned in a north-south direction.

The Imprint of Laneways at Meeting House Lane:

The years leading up to the mid-seventeenth century witnessed significant changes in the townscape, primarily an increase in the number of streets, lanes and buildings. The Corporation of Cork and the town’s wealthier merchants were central to the creation and modification of the urban townscape.

As a result, the 1641 Royal survey of Cork records that the number of streets and laneways in the town had increased to sixty-nine, while in the suburbs it had increased to twenty-four. Thus, the total number of streets and laneways in the urban area in 1641 was 93. The estimated number of domestic dwellings in 1602 in the town and suburbs was c.445, by 1641 the official number given was 1,266 dwellings.

The High Cross Site & Life Within the Walled Town:

George Carew’s map of Cork just shows the buildings of the walled town and nods to its economic wealth. There are very few nods to daily life within the town. Perhaps the base of his depicted town cross, which gives a voice to the town’s citizens.

Daily life in seventeenth century Cork would have been difficult. Overcrowding was common in poorly ventilated dwellings, whilst the water supply was subject to contamination from sewerage and improper rubbish disposal. Household waste was thrown onto the streets and laneways and dead animals were left to decay where they fell. The upper-floor of the residences usually projected out into the street, blocking out the light and lending the town a gloomy aspect.

The streets were poorly paved and very muddy due to tidal water seeping up through the marshy ground. The air would have been damp and heavy, and as a result many diseases were rampant, including; measles, mumps, influenza, leprosy, chicken pox, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, typhus and whooping cough. Inadequate personal hygiene would also have meant that fleas lice were common.

Watch an RTE Archives film from 1990 on life within the walled town within the context of an archaeological excavation at Grattan Street: Click here:RTÉ Archives | Environment | Digging Up the Past of Cork City (rte.ie)

The Great Fire, 1622:

Several archaeological excavations have revealed evidence for the construction of different types of houses within the walled town. The remains of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Anglo-Norman houses comprised post-and-wattle houses and sill-beam houses. For the first 300 years of the walled town’s history, it was illegal to leave a fire lighting at night, a misdeamenour punishable by a heavy fine, known as ‘smoke silver’.

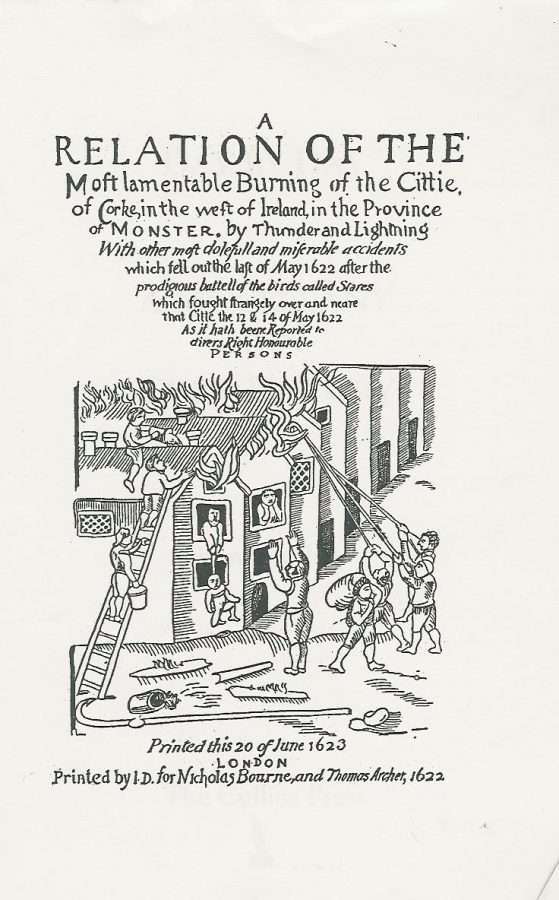

Indeed, the building of timber houses within the town was condemned in May 1622 when on the last day of this month, a large fire swept through a large portion of the town. It was not, however, caused by mismanagement of domestic fires but by lightning striking one of the timber houses on North Main Street.

Contemporary descriptions in the council books of Cork Corporation detail that 1,500 houses were burnt down and that the northwest and southeast parts of the town were destroyed. A contemporary account by an unknown author describes how the inhabitants saw a ‘dreadful lightning with flames of fire break out of the clouds and fall upon the cittie at the same instant at the east and the highest part of the cittie .. there the fire began with horrible flames.’

St Peter’s Avenue and The Heritage of Laneways:

Perpendicular to the main street narrow laneways, which provided access to the back gardens of the houses overlooking the main street (128 recorded in 1654 A.D).Archaeological excavations have revealed that early on in the walled town’s life, a laneway existed at either side of each side of a pair of houses but occupied the property of only one of the houses. Early laneways consisted primarily of wooden platforms.

In the late 1300s, the laneways were regularised within the back gardens or burgage plots of houses. In many cases, floor space was lost by many property owners, which in turn caused problems for the Corporation running the city.

Later laneways consisted of roughly cobbled laneways with stone gullies.

The laneways at any time during the walled city’s lifetime would have been covered with rubbish. Thus, creating a breeding ground for vermin and disease.

Only a handful of laneways have survived to the present day.

READ more on the history of the medieval laneways in Gina Johnson’s excellent book, The Laneways of Medieval Cork.

LISTEN to Gina Johnson in Conor O’Toole’s Podcast series:

The Laneways of Medieval Cork: Episodes & Podcasts (corklaneways.blogspot.com)

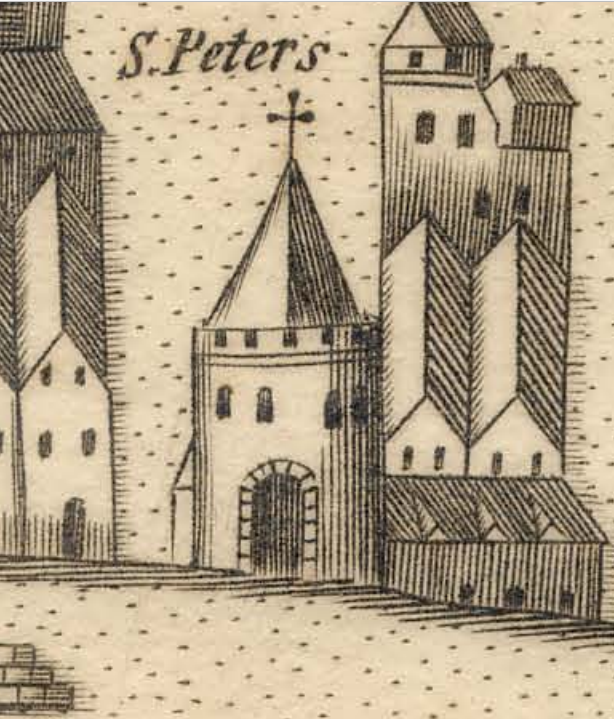

St Peter’s Church:

Present day, St Peter’s Church, is the second church to be built on its present site overlooking North Main Street. The first church was built sometime in the early fourteenth century. In 1782, the church was taken down and in 1783, the present limestone walled church, was begun to be built. At a later stage, a new tower and spire were added to the basic rectangular plan. The new spire though had to be taken down due to the marshy ground that it was built on.

In recent years and in accordance to the aims of the pilot project of the Cork Historic Centre Action and the finance of Cork City Council and operational support of Cork Civic Trust, St Peter’s Church has been extensively renovated and opened as an arts exhibition centre.

One of the most interesting monuments on display in the church is the Deane monument. This monument, dating to 1710, was dedicated to the memory of Sir Matthew Deane and his wife and both are depicted on the monument, shown in solemn prayer on both sides of an altar tomb.

Colman’s Lane & its Heritage Plaque:

Objects found in archaeological excavations are depicted in heritage plaques on the ground on North Main Street, which also mark the site of historic laneways. The plaque at Colman’s Lane depicts the large amount of iron objects, which have been found by archaeologists, including knives, spearheads, nails, horse tack, tools, such as drill bits, shears, gouges and punches, barrel padlocks and keys.

Bronze objects such as stick-pins (dress fasteners), buckles needles and keys have been found, and Lead objects, such as lead weights. Bone manufacture was common in the town, too. The underlining marshy soil in the city provides perfect conditions for the preservation for bone artifacts, such as bone combs from antlers of deers; antler gaming pieces such as chessmen and dice, bone needles, spindle whorls, bone harp pegs and toggles.

Numerous wooden artefacts have been found and represent the use of several species of native tree. Each was utilised in a different way according to which type of object was being produced. For example, oak was favoured for the frameworks of building and for furniture. Ash was used in the making of bowls as it was easy to carve. Yew was favoured in carving and stave-making. Leather artifacts, especially footwear, belts, straps and sheaths, also form a large portion of the archaeological record.

The importance of the leather industry is reflected in the fact that grants were given by Queen Elizabeth I in the late 1500s to the guilds of shoemaking, glove-making and tanning. Textiles mainly took the form of woven or spun silk, wool or animal hairs.

Skiddy’s Castle:

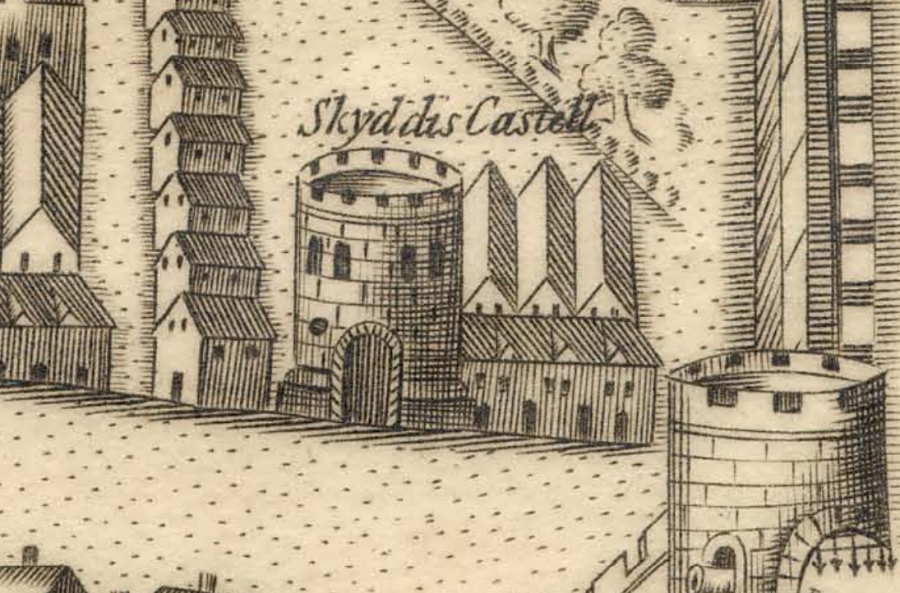

George Carew’s depiction of the walled town, c.1585-1600 shows two tower houses or castle-like structures on North Main Street. These residences, Skiddy’s Castle and Roche’s Castle, belonged to two wealthy and influential merchant families. The Skiddy family was reputed to be descended from Scandinavian merchants who established themselves in Cork around 1445.

Skiddy’s Castle was one of the most famous landmarks in the walled town of Cork. It was a tower house built in 1445 or 1447 by either John or William Skiddy. In 1603 the castle was taken over and used as a royal gunpowder magazine until 1770. The castle is shown on all the ancient maps of Cork, where is depicted as both a round and a rectangular structure. No trace of the castle remained above ground.

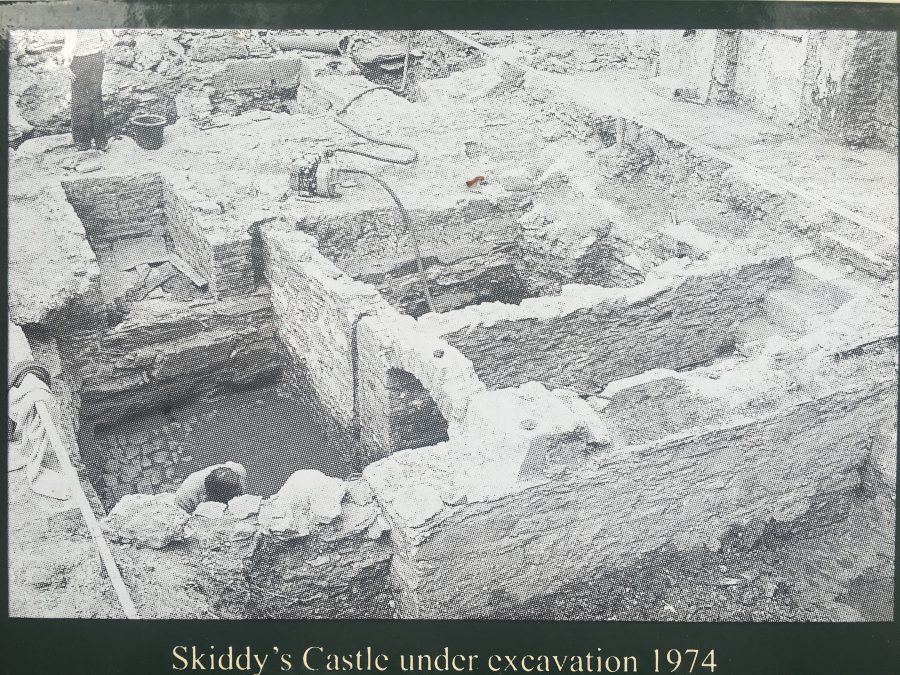

In 1974, excavations near North Gate Bridge on North Main Street, in the area of then present-day National Rehabilitation Board, revealed the base of Skiddy’s Castle.

The ground floor room survived almost intact beneath the modern surface. The plan was rectangular and the room was divided in two by a partition. The walls stood to a height of almost two metres above a wooden raft. Pointed wooden stakes were used as piles to strengthen the foundations.

A two-metre high stone mantlepiece was found with the inscription “1597 GS” with floral motifs. The mantlepiece was incorporated into the Cork Volunteer Centre on North Main Street and placed high above the main entrance where it can still be seen.

Iron smelting on the The Gate Cinema Site:

Archaeological evidence indicates the presence of several crafts within the city. The largest of these was the craft of metal-working, and large quantities of iron slag have been found along with iron-smelting furnaces. The most significant of these was revealed during the placing of foundations for the Gate Cinema on Bachelor’s Quay in 1994, where a blacksmith’s forge was discovered dating to the early half of the fourteenth century.

The Kyrl’s Quay Find – 800 Years of Legacies:

The archaeological report pertaining to the Kyrl’s Quay re-development of the early 1990s and published by Cork Corporation and edited by Dr Maurice Hurley, is a worthy edition to the library of any urban scholar.

In advance of redevelopment of the site as a multi-storey carpark and shopping centre. Cork Corporation in May 1992, on behalf of the developer conducted Archaeological work. A total of 580 sq.m in was completed by the beginning of July.

The earliest occupation levels explored were 13th-century in date. No remains of medieval houses were discovered in the core section of the site, but discoveries on the post and wattle property boundaries of the burgess plots as well as storage and cess-pits were present. For 800 years, the property boundaries remained practically unaffected.

Adjacent to North Main St the incomplete foundations of thirteenth/ fourteenth century timber framed houses were unearthed. Later, these houses were re-built in stone.

Between July and September sixty metres in length of the town wall were excavated. The extant wall rose to a maximum height of 3.2m. It was mostly of thirteenth century date but included some segments, which were re-constructed at later times. Within the wall were two gateways. One had a paved slipway through which small boats could have been pulled up. iron hinge pivots and Bolt holes for a wooden door were discovered.

At the north-west end of the excavation the foundations of a tower or mural turret were found. This was one of the towers which were located regularly along the circuit of the town wall. The tower had a strong base faced with dressed limestone blocks on the battered foundation. It had a shaped projection from the town wall.

The archaeological report concludes that the town wall, which would have functioned as a quay as well as a defensive wall, may have stood to a height of 6m or more. Over the course of the 500 years that it was in use, up to three metres of silt and debris from human occupation amassed on either side of it. When it was razed to ground level in the eighteenth century, the lower wall levels continued sealed below the ground.

Many artefacts were found. Nearly 10,000 pottery sherds were unearthed with many of them hailing from wine jugs imported from the Saintonge area of south-west France and from Bristol, England. Many artefacts made from wood, leather and bone were also uncovered.

Ten metres of the town wall was preserved for public display purposes underneath the entrance ramp into Kyrl’s Quay Multi-Storey Carpark. The current key holder is the Cork City Council Executive Archaeologist.

North Gate Bridge:

As the northern access route into the walled town North Gate Drawbridge was a wooden structure and was annually subjected to severe winter flooding, being almost destroyed in each instance. In May 1711, agreement was reached by the council of the City that North Gate Bridge be rebuilt in stone in 1712 while in 1713, South Gate Bridge would be replaced with a stone arched structures. The new North and South Gate bridges were designed and built by George Coltsman.

Between 1713 and the early 1800s, the only structural work completed on North Gate Bridge was the repairing and widening of it by the Corporation of Cork.

It was in 1831 that they saw that the structure was deteriorating and deemed it unsafe as a river crossing for horses, carts, and coaches. Hence in October 1861, the plans by Cork architect Sir John Benson for a new bridge were accepted. In April 1863, the foundation stone for the new bridge was laid. The new bridge was to be a cast-iron structure with the iron work completed by Ranking & Co. of Liverpool. An ornate Victorian style was incorporated into the new structure with features such as ornamental lampposts and iron medallions depicting Queen Victoria, Albert the Prince Consort, Daniel O’ Connell, the Irish ” Liberator ” and Sir Thomas Moore, the famous English poet.

On 6 November 1961, the new and present day bridge, of concrete slabs was opened by Lord Mayor, Antony Barry TD. The new bridge was named Griffith Bridge in honour of Arthur Griffith who was a famous Politician / Republican in Ireland in the early 1920s.

ENDS.

Some Sources:

-The information is abstracted from various articles from my Our City, Our Town column in the Cork Independent, 1999-present day, Cork Independent Our City, Our Town Articles | Cork Heritage

– READ the Exhibition at Elizabeth Fort

– SEE the artefacts from the Walled Town of Cork at Cork Public Museum,

Our Collections – Cork City Council

– READ the website of the City Archaeologist, Archaeology – Cork City Council.

– READ the best overview of excavations of the town wall, click below:

Cork City Walls Management Plan by Cork City CouncilDownload

– CLICK on the sites recorded within Excavations.ie. This site contains summary accounts of all the excavations carried out in Ireland – North and South – from 1970 to 2013, Maps New « Excavations

– WATCH short films at Archaeology – Cork City Council and

Archaeology Lecture: Life in Medieval Cork on Vimeo

– READ the multiple archaeological reports on Medieval Cork in Cork City Library. In particular check out any work by Dr Maurice Hurley & Rose M Cleary.