Trail starts at St Patrick’s Bridge.

Below is a brief historical walking trail, which covers some of the topics on my physical walking tours. The information is abstracted from various articles from my Our City, Our Town column in the Cork Independent, 1999-present day, Cork Independent Our City, Our Town Articles | Cork Heritage

Introduction:

The curving and elegant thoroughfare of St Patrick’s Street was, is and will always be the common ground where all Corkonians mix. A street of great character, a chequered past provides the setting for Cork’s principal boulevard.

Strolling down St Patrick’s Street or affectionately known in the native tongue as “Pana” is a pleasure. Being the main thoroughfare in a city such as Cork is unique in itself, but being from Cork, one is bound to meet a relative or friend. Perhaps, it is its role as a meeting place that provides the street with its rich appeal.

The street’s cultural heritage is rich. The area of and surrounding St. Patrick’s Street was the brainchild of city merchants in the early eighteenth century. Prior to the eighteenth century, the area was just marshland, which was reclaimed as the eighteenth century progressed. Indeed, St Patrick’s street was a curving channel of the River Lee and turned into a canal with quays, shops and warehouses on both sides of it. Circa 1780, the canal was filled, which created a wide and elegant thoroughfare.

During the late 1990s, the Catalan architect Beth Gali was chosen by the Corporation of Cork to recover the public space of the street for citizens. The entire street was repaved in high quality materials, granite and limestone, and the pavements widened to create plaza areas.

The Great Expansion:

For nearly five years, the walled town of Cork (c.1200-c.1690) remained as one of the most fortified and vibrant walled settlements. However, political events and civil unrest amongst citizens in the late seventeenth century culminating in the ‘Williamite’ Siege of Cork 1690, provided the catalyst for large scale change within the city itself. The ensuing breaches in the medieval walls meant, that in a sense, the town’s defensive spell had been broken.

Due to an absence of finance in the coffers of the municipal governing body, the Corporation of Cork, the town walls of Cork were allowed to decay. This decay in the walls was to inadvertently alter much of the city’s physical, social and economic character in the ensuing century, creating a distinct phase in Cork’s historical development known as ‘Georgian Cork’.

In the early 1700s, large portions of marshland to the west and east of the town were to be reclaimed in the early 1700s by the Corporation of Cork and two influential religious groups who were lessees of the Corporation, the Huguenots and the Quakers. Residences, bridges, quays In general, five main developments occurred on the bought or leased-out marshes, drainage, residences, streets, quays and bridges.

The first one was the building of residences on them. Buildings that were constructed overlooking quays had steps leading up to their front door in order to prevent channel water from flooding out the building. These types of houses can still be seen on the South Mall and on St. Patrick’s Street especially the entrance to the Chateau Bar today.

After 1690, the civic administration of the town especially the roll call of mayors and sheriffs suggest a new ruling class and their established Protestant church in the town. The names of old English merchant families disappear such as the Galways, Skiddys, Roches, Goulds, Meades Coppingers and Tirrys. After 1690, new surnames of merchantile families based in Cork are recorded, which included, Maylor, Winthrop, Tuckey, Lavitt, Pembroke, Brocklesby and Deane. Many of these names form street names adjacent St. Patrick’s Street.

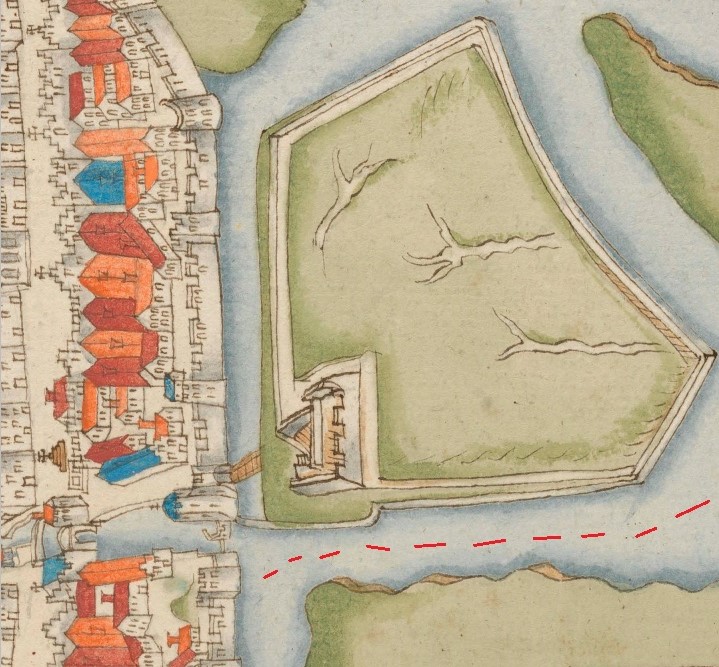

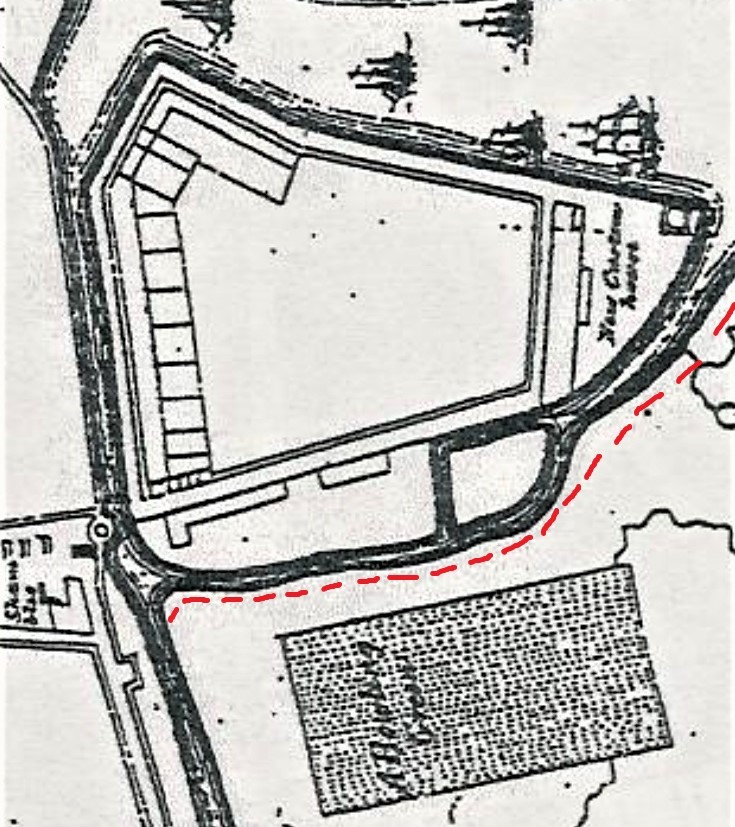

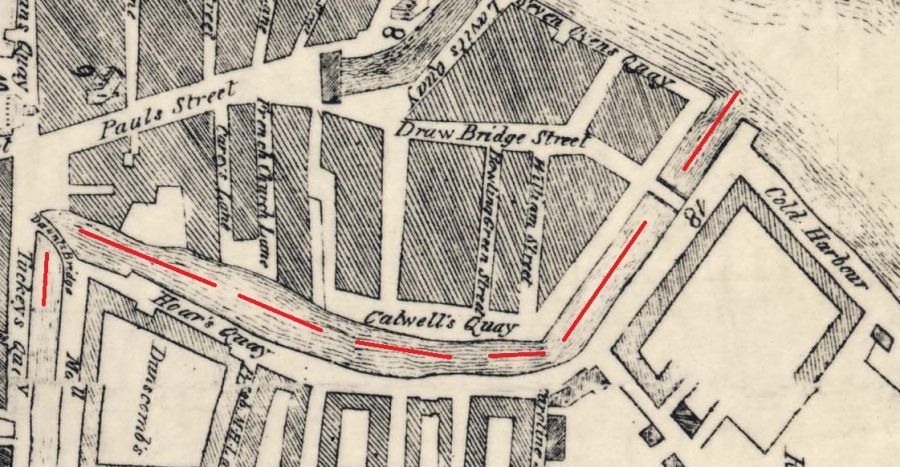

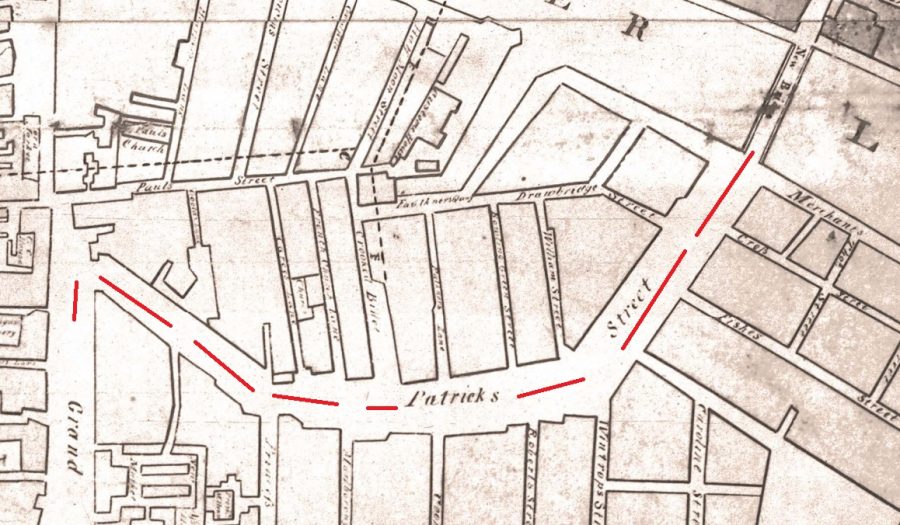

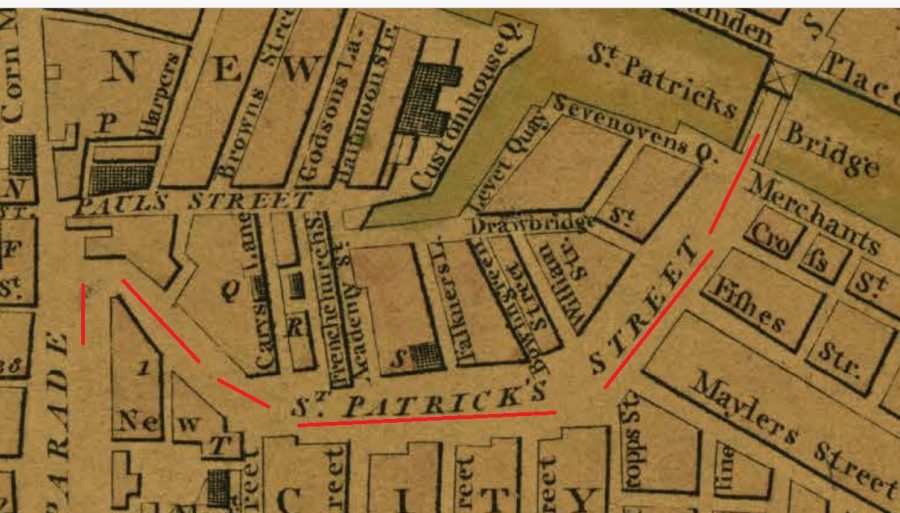

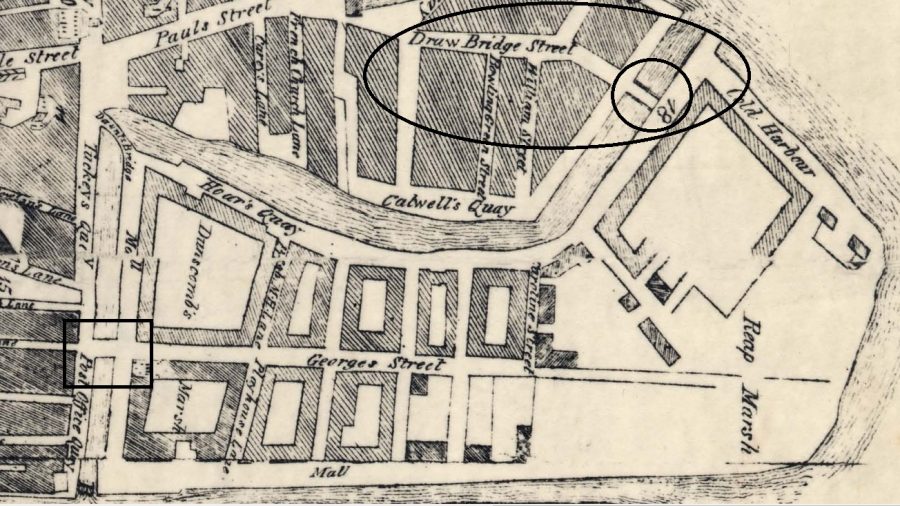

Mapping St Patrick’s Street area, From Canal to Street, 1600-1801:

plus the river channel, which was to become St Patrick’s Street (source: Cork City Library)

Drawbridge Street:

One particular and significant venture, which was recorded at length in the Corporation’s council books in the eighteenth century, was the agreement between Alderman Tuckey and the Dunscombe family in 1698. In mid January 1698, Captain Dunscombe was given liberty to build a stone bridge from Tuckey’s quay onto his leased marsh. The bridge in today’s terms extended across the Grand Parade by the Berwick Fountain. The Corporation of Cork required that the new bridge have arches high and broad enough for a small boat to pass under at high tide and must be kept in repair by the Dunscombe family and their heirs.

A pre-condition required by the Corporation pertaining to the bridge’s construction was that Dunscombe was obliged to build a drawbridge spanning the “curving channel of water” . In today’s terms, the drawbridge spanned from the site of what is now Debenhams to what is now the Eason’s side of St. Patrick’s Street.

Regarding the drawbridge, Dunscombe was obliged to wait for the Corporation to fix the official width of the eastern channel. Consequently, this measurement was to be used in the construction of quays in the later eighteenth century. Drawbridge Street, adjacent to St Patrick’s Street today, highlights the existence of the former drawbridge in the area.

St Patrick’s Bridge:

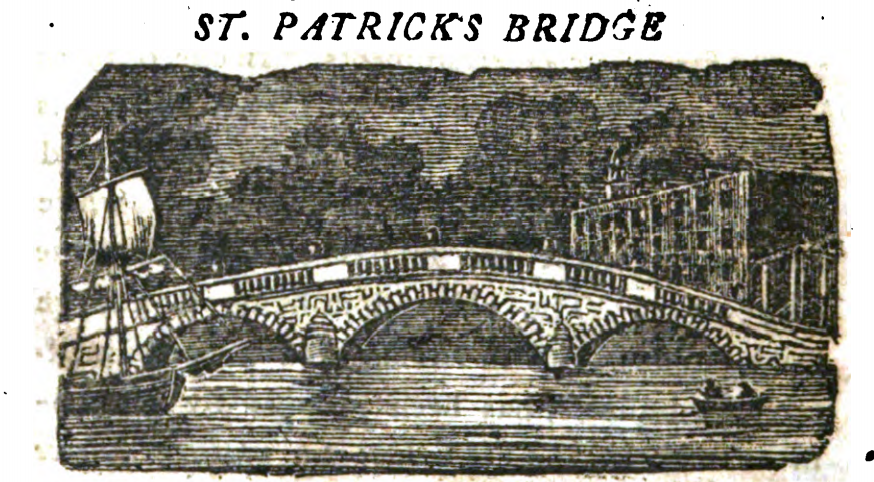

In the mid-eighteenth century, industry in Cork was rapidly growing. The manufacture of cloth-weaving, wool-combing and cotton were important to the city’s commerce. The Port of Cork was used as a place for meeting other ships of the same nature. These ships came from and went to places like the West Indies and the east coast of the United States up to the American War of Independence. However, it was the butter trade that made Cork a wealthy city. Butter was exported to every part of the known world from the butter market. Since many of the industries in Cork in those days were based on the north side of the city, a new bridge was proposed by the expanding population.

Opposition also reigned in the city, especially the businessmen near the proposed site and the ferry boats that operated the River Lee. Their petition to the council was turned down and in 1786, the go-ahead for the raising of money for the project was given. It was decided by the council of the city that loans would have to be taken out and would have to be paid back with interest. However, the loan or the £1000 contribution from the council was not enough to pay back the financial institution plus interest that loaned the money. Tolls were placed on the proposed bridge and the aim was to abolish them 21 years later. Michael Shanahan was chosen to be the architect and chief contractor of the operation. On 25 July 1788 of that year, the foundation stone was laid.

Unfortunately, on 17 January 1789, during construction, disaster occurred as a flood swept through the Lee Valley. A boat tied up at Carroll’s Quay (then Sands Quay) broke loose and crashed against the uncompleted centre arch i.e. the keystone and destroyed it. Michael Shanahan was devastated and set off to London to find new prospects. He returned though to rebuild the bridge which was christened on 29 September 1789.

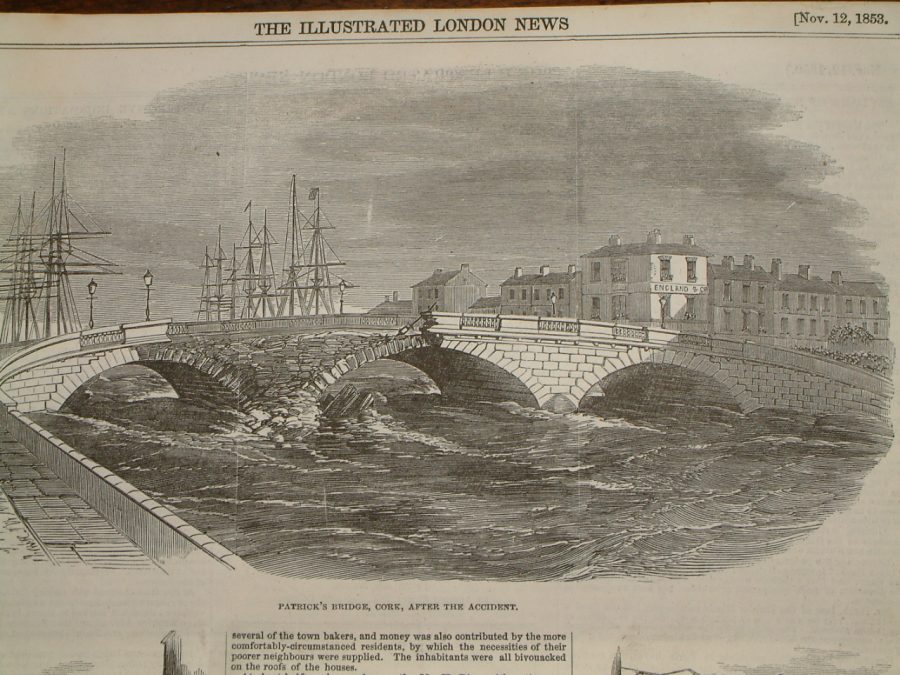

Fast forward to November 1853, disaster happened again when St. Patrick’s Bridge was swept away by flood. This was due to a build-up of pressure at North Gate Bridge, which was the only structure to remain standing whilst the flood swept over the city centre claiming several lives and destroying everything in its path. John Benson was to be the architect and he chose Joshua Hargrave, the grandson of the Hargrave that worked on the first bridge and other contractors to build the structure. Hargrave was chosen, mainly because of his reputation and the price of building the bridge.

In November 1859, the new St Patrick’s Bridge was opened and christened. Disaster struck again when the bridge had to be reconstructed due to a ship which struck it. It was built again and was opened on 12 December 1861 for public traffic. From here on the Bridge’s luck has remained intact and still elegantly spans over the rushing waters of the River Lee.

During 2018-2019, a €1.2m bridge revamp was funded by Transport Infrastructure Ireland, in conjunction with Cork City Council. Cumnor Construction cleaned, repointed and repaired the stonework and drafted in specialist repair and restoration experts to restore to its former glory the bridge’s original lamp columns. The bridge’s footpaths have been widener, its carriageway resurfaced and new road markings put in place.

READ: Niall Murray presents “As repair on Cork bridge continues, rare picture from 1861 emerges”, As repair on Cork bridge continues, rare picture from 1861 emerges (irishexaminer.com)

VIEW: Iconic photos of St Patrick’s Bridge ahead of formal reopening, Iconic photos of St Patrick’s Bridge ahead of formal reopening (echolive.ie)

READ: Eoin English’s article, “An army of Paddy’s packed onto Cork’s landmark St Patrick’s bridge to mark the completion of its €1.2m refurbishment”, In Pictures: Were you one of the 158 Paddys in Cork yesterday? (irishexaminer.com)

VIEW BELOW: Stunning time-lapse & video footage for Cork City Council of the refurbishment of St Patrick’s Bridge with Lensmen Photography and Video Production

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=87nEoFL1f2s

Beneath the City – A Street Culvert:

At low tide on St Patrick’s Bridge, look into the river on the eastern side where the bridge meets Merchant’s Quay; here is one of the city’s culverts. On eighteenth-century maps of Cork City, a myriad of quays and canals are shown across the emerging city. Cork’s central canal lined the centre of the newly reclaimed area, admirable buildings on both sides bearing a special relationship with the water. By 1790, many of these were to be filled creating wide and spacious streets like St Patrick’s Street, Grand Parade and the South Mall.

Very little is known on the nature of city’s culverts, many of which in the past straddled river channels of the Lee. Every now and again, utility and Corporation workers dig up our streets and encounter the culverts and ultimately many have to be replaced to accommodate the modern city. On 14 October 1924, Mr Ryan, the Council’s Building Inspector, submitted an insightful report to the City Councillors on the condition of the underground arch under St Patrick Street. He drew the Corporation’s Public Works committee to a number of defects.

There was a noticeable increase in the tendency of the arch stone to slip. The side walls forming the abutments of the arch were in a wretched condition; in parts they resembled more a heap of stones loosely tipped from a cart than a wall systematically built. A considerable amount of silt helped to save those side walls from the scouring action of floods, and by its weight to retain them in position. The loose open joints of these walls admitted the free tunnelling of rats to adjoining premises. The continual working of the tide through these walls removed a certain amount of subsoil, and this the architect proposed would eventually lead to a subsidence of the adjoining ground with the drainage connections.

The unbraced concrete foundation of the pavement and the wood blocks above, both of which were atop the foundation over the arch saved it to a great extent. As the high tide level was much higher that the crown of the arch, the tide removed supporting soil. An amount of timbering or bracing had been fixed in the archway. The archway was the main sewer of the city, and received the sewage from all the sewers in the side streets; it’s bed was the old river bed and even if in good condition, it was self cleansing. The city’s tram lines were directly over it in places, and an amount of inconvenience would be experienced by the failure of any part of the arch.

The architect concluded with options for replacing the archway with a pre-cast concrete pipe, a small brick sewer or concrete culvert.

Fr Mathew Statue:

For over 150 years the Fr Mathew Statue has stood at the eastern end of St Patrick’s Street. Enshrined in Cork City’s collective memory as the ‘Apostle of Temperance’, by the end of 1840, it is recorded that 180,000 to 200,000 nationwide had taken Fr Mathew’s pledge. In the late 1840s, Fr Mathew went to North America to rally support for his teetotaller causeand the teetotalism cause in Ireland and England started to suffer by his absence. He died in December 1856 and was buried in St Joseph’s cemetery, Cork, his own cemeterythat he created for the poor.

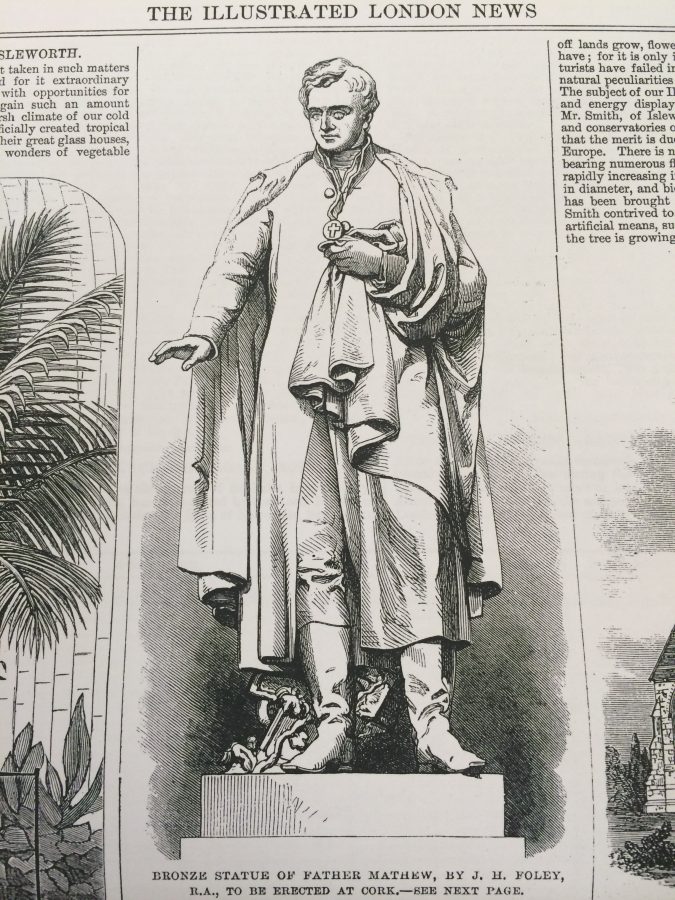

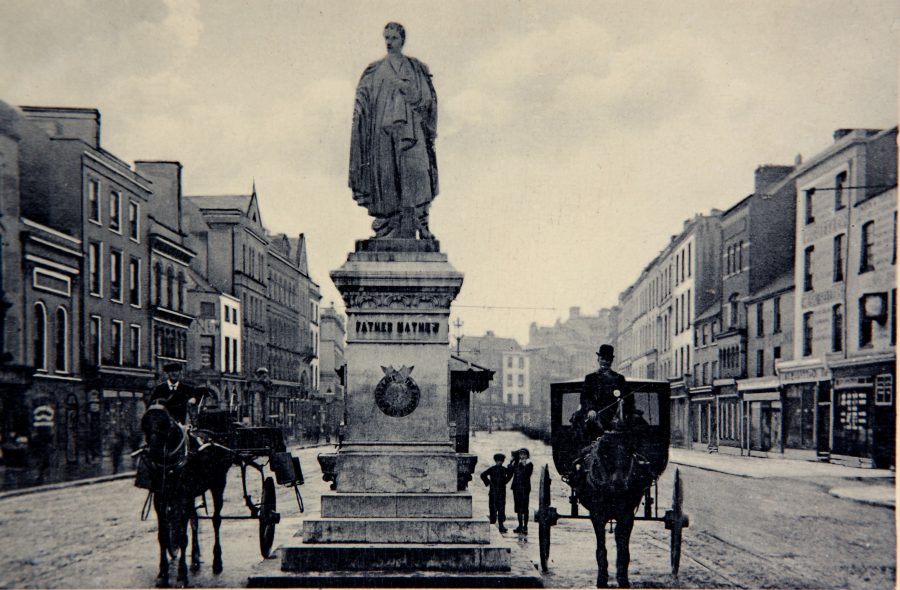

Fr Mathew has left a legacy in this city that has been maintained and respected since his death. Of all his commemorative features in the city, the Fr Mathew Statue, erected in 1864, on the city’s St. Patrick’s Street very much honours the man.

Soon after the death of Fr Mathew in December 1856, a committee was formed for the purpose of erecting a suitable memorial in the city. The commission was entrusted to the famous sculptor John Hogan who in his early days had been raised in Cove Street and was acquainted with Fr Mathew. Hogan died in 1858 and on his death a meeting of the committee was called. The commission was handed over to John Henry Foley. At 40 years of age the sculptor had achieved the highest honours. Foley’s output was prodigious and his works are to be found in India, USA, Ceylon, Ireland and Scotland. His subjects were deemed classical and imaginative, creating equestrian statues, monuments and portrait busts. Two years after the unveiling of Fr Mathew statue, his Daniel O’Connell monument in Dublin was unveiled.

The Fr Mathew Statue was unveiled on 10 October 1864 amidst a concourse of people and public celebration. Both the Cork Constitution and Cork Examiner the following day carried lengthy and vivid accounts of the pomp and ceremony. The statue had been cast in the bronze foundry of Mr Prince, Union Street, Southwark, London. As well as obtaining a remarkable likeness of Fr Mathew, the sculptor posed the figure as a representation of him in the act of blessing those who had just taken the pledge. On the statue’s arrival in Cork, it was placed on the stone pedestal which had been designed by a local architect William Atkins.

The proceedings on 10 October began at noon when it was estimated that thousands of people lined all the vantage points on the city’s streets. All businesses had been suspended for the day and public buildings and private houses were decorated for the occasion. The city remained thronged with people from 10am to 4pm. A huge procession had assembled on Albert Quay and the Park Road and moved off at 12noon headed by the Globe Lane Temperance Society of 50 members and 12 performers in their band.

All the trades, societies with their banners, sashes and coloured rosettes marched with Temperance Societies from all over the county. At 2pm the statue was unveiled to a mass of public support. Henceforth it was immortalised as a landmark, defining the centre of the city and supporting the story and folklore of Fr Mathew on the great St Patrick’s Street.

Cork City Libraries has published a book on the history of the Father Mathew statute in Patrick Street (by Antoin O’Callaghan). The book celebrates the history of one of Cork’s most iconic monuments. The book can be purchased from Cork City Libraries.

Fireman’s Hut:

Adjacent the Fr Mathew Statue was the fireman’s hut, which has rescue equipment and one man on duty at it during night time hours. In 1910 there were three brigade stations, a central one on Sullivan’s Quay and two auxillary stations – one at the rear of the Courthouse on Grattan Street and one at the top of Shandon Street.

The engines at this time were two Merryweather steam pumps, which were drawn by teams of horses and these were purchased in 1892. The Brigade at that time consisted of six regular men and two Turncocks living on the station with six auxiliary firemen, all Corporation employees, and with local volunteers in all a force of 30 men could be mustered in a few minutes. A report from the Chief at the time suggested that a night response took about 2.5 minutes with men fully dressed and horses out.

Mangan’s Clock:

In early 1891 on St Patrick’s Street, opposite St Patrick’s Bridge a pillar clock was erected. It is a large double-faced drum perched upon a wrought-iron pillar twenty-three feet high. On the premises of the Mangan business was the turret clock machinery which, by means of a rod underneath the pathway, and rising through the centre of its supporting pillar to the drum, worked the hands. By this system the clock was easily wound and regulated.

The Mangan company was founded in Cork in 1817 by James Mangan, clockmaker (who was born in Caroline Street, Cork in 1793). John Francis Maguire in his book entitled The Industrial Movement of Ireland (1853) note the reputation of the Mangan family and of the growing need for telling the time to a public audience especially in an age where everyone did not have a watch;

“Within the last twenty years, the attention of various public bodies in Cork has been directed to the better regulation of time and the liberality of one of those bodies has afforded a fitting field for the display of the genius and mechanical skill of a local’ tradesman—Mr James Mangan whose work has been pronounced, by the best judges, to be equal to any in the world, and whose monster clock in the Church of St Anne’s Shandon is one of the largest, if not the largest, in Europe. His clock on the Corn Market—in which, with the adjoining buildings, the National Exhibition was held—has five dials, one inside the buildings, and one on each of the four exterior sides of the turret. But his grand work is the Shandon Clock created by order of the Corporation”.

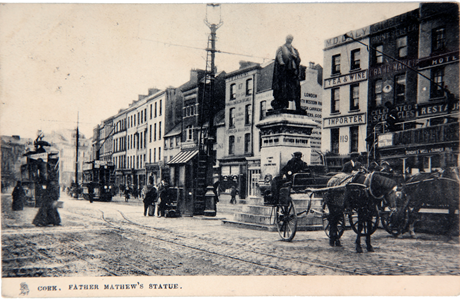

Trams, St. Patrick’s Street:

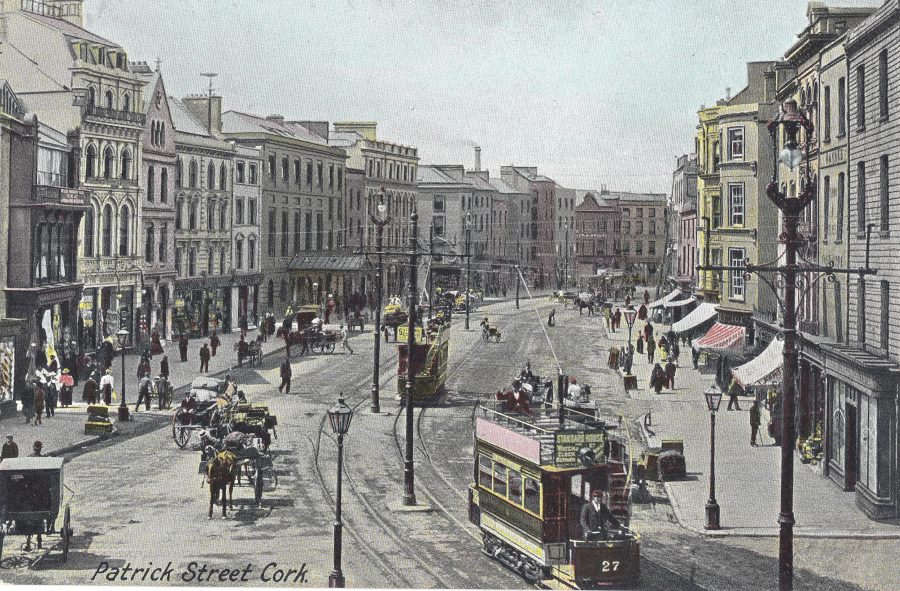

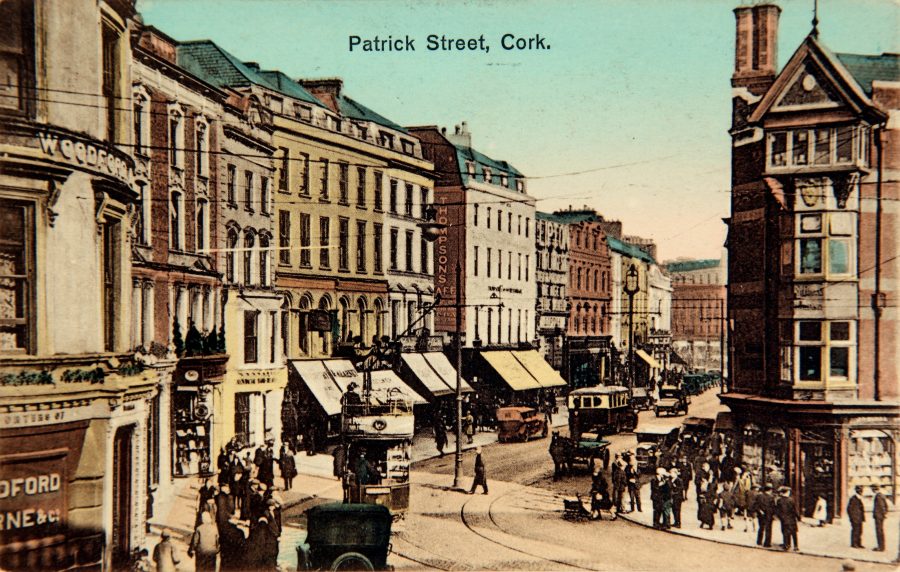

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, the Corporation of Cork planned to establish a large electricity generating plant. The plant would provide public lighting and operate an electric tramcar extending from the city centre to all of the popular suburbs. Eighteen tramcars arrived in 1898 for the opening, which occurred on 22 December.

Cork was to become the eleventh city in Britain and Ireland to have operating electric trams. Four of the six suburban routes were complete for the line’s commencement. The eventual termini included Sunday’s Well, Blackpool, St. Luke’s Cross, Tivoli, Blackrock and Douglas. The city centre tram termini was on St Patrick’s Street Time adjacent James Mangan’s Clock on the street, which told the time.

By 1900, 35 electric tram cars operated throughout the city and suburbs. They were manufactured in Loughborough, U.K. and all were double deck in nature, open upstairs with a single-truck design. Most tram cars could hold at least 25 people upstairs and 20 downstairs. However, a key rule on the tram was that nobody could sit or stand on the driver’s front platform!

VIEW: Tram Ride from King Street to Patrick’s Bridge and St Patrick’s Street, Cork (1902) by Mitchell & Kenyon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DXXtYqFCncE

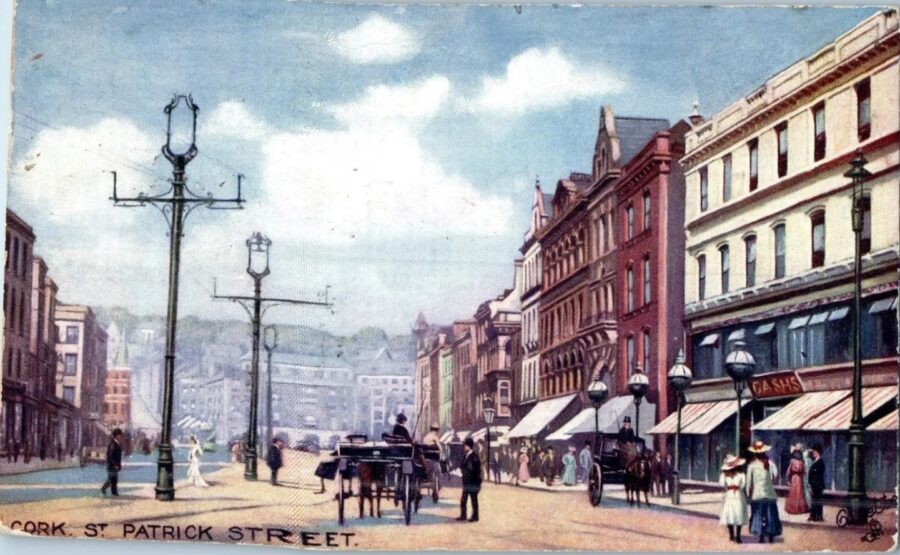

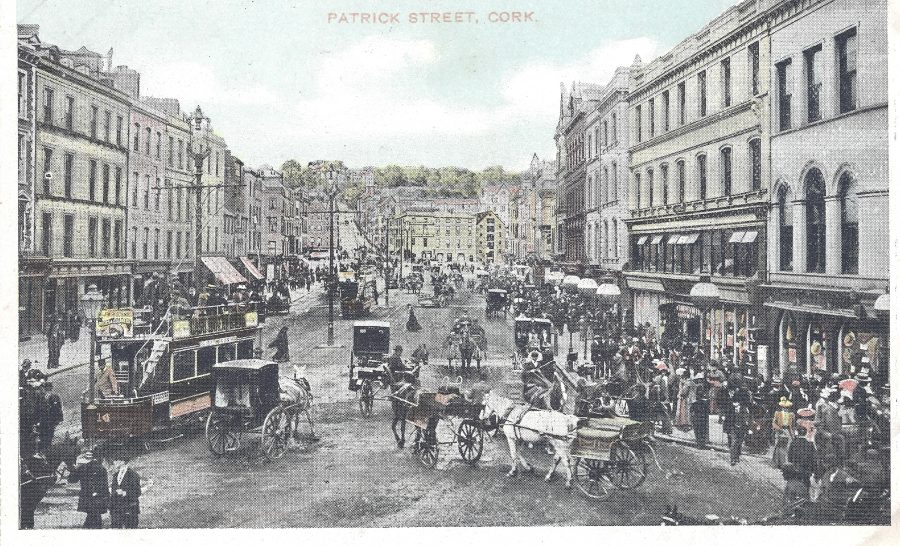

St Patrick’s Street, 1911:

Eastern St Patrick’s Street, 1911: In 1911, the street directories for the city record a busy street of varied businesses. On the right hand side of this old stereograph, the businesses listed from the corner of this street to the people on the right included Barry’s wine and spirits, Russell’s provision warehouse, Mangan’s watchmakers, Silversmiths and Opticians, Henry O’Shea’s Tivoli Restaurant, Clarke & Son’s tobacco manufacturers, John Blair & Son’s pharmaceutical chemists, Andrew & Co’s newsagents and stationers, O’Grady’s tobacconist, Lamkin Brothers, tobacco manufacturers, James Simcox’s grocers, the Hill’s dress warerooms, Andrew’s teeth specialist, Evan’s booksellers, O’Sullivan’s Tobacconists, Criger’s dentistry, Wolfe’s ladies outfitters, London House warehousemen, James Archer’s engravers, John Belas’s commercial agency, Harte’s dress warerooms, Lee Boot Manufacturing Co, Scully, Connell & Co’s Children’s outfitters, and Cash and Co’s drapers and general warehousemen.

Central St Patrick’s Street, 1911: On the left of the postcard below), the Munster Arcade was one of the principal department stores in Cork on St Patrick’s Street. It was well known for its selling of Irish linens, Irish made tweeds, cheviots and serges. On the right of picture, from the bottom right, the businesses included, Foley’s Bookseller and stationer, Breton & Son’s Jewellers, Smith’s Stores, Grocers and Wine Merchants, The Berliz School of Languages, the agency of the Great Western Railway of England, the agency of Dunville & Co’s Distillers, Herbert Fox’s Insurance Agency, and Hatton’s Fish & Poultry Store., Munster Fresh Meat Depot, and Cork Examiner Offices. The area today recently witnessed the opening of a new shopping street; Faulkner’s Lane was re-named Opera Lane.

Western St Patrick’s Street, 1911: The elegant St Patrick’s buildings in 1911 hosted a number of prominent businesses included the Paris Photographic Studio, Irish Times offices and Teape’s Jewellers. From the bottom left, the businesses shown are Woodford Bourne and Co. grocers and wine Merchants, Miss Dale’s Music School, Fielding’s chemists and opticians, Provincial Bank of Ireland, Guy & Co’s Wholesale paper merchants, Domestic Bazaar Company, Cole’s Income Tax Office, Allen’s clothier, Guy and Co’s stationers with their associated photographic studio, and Thompson and Son’s bakers and confectioners.

BUY Cork City Through Time by Kieran McCarthy & Dan Breen here,

Cork City Through Time: Amazon.co.uk: McCarthy, Kieran, Breen, Daniel: Books

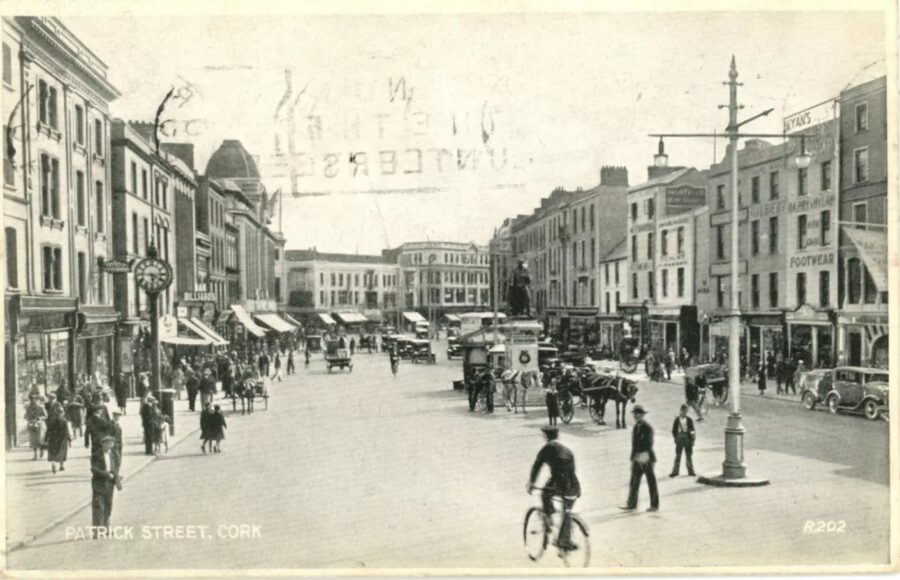

Rebellions, Burning and Rebuilding: Circa 1920:

In the 1910s Ireland’s War of Independence was a dark time for the country. Violence escalated on both sides between Ireland and Britain. Eamonn DeValera and his unofficial government, Dáil Ēireann struggled to break Westminster’s grip on Ireland. During this period, Cork had a strong rebel nature. The city’s uncompromising stance was epitomized by two men: Thomás MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney.

In response to Irish Republican Activities in Cork and in the country as a whole, from January 1920, the British government increased the number of men serving in the Royal Irish Constabulary, recruiting the infamous Black and Tans to swell the ranks. The total number of British government servants in Ireland came to approximately 40,000, whilst the IRA numbered 5,000 men. Thus, more often than not Irish Republican Army employed hit-and-run tactics. On 28h November 1920, a famous incident involving the British auxiliaries and the IRA occurred near Cork. The ‘Flying Column’, a division of the West Cork IRA, ambushed a police patrol near the village of Kilmichael, just south of Macroom. Twenty British soldiers were killed. In West Cork and in Ireland as a whole, Kilmicheal became a celebrated victory of rebel arms. Indeed, the column commander, Tom Barry, became a folk hero and a revolutionary celebrity.

In December 1920, six unknown IRA men ambushed a troupe of auxiliaries within a hundred metres of the central military barracks near Dillion’s Cross on the northside of Cork City. At least one auxiliary was killed and twelve others wounded. In retaliation, indiscriminate shooting commenced by the auxiliaries and Black and Tans in the main city centre streets shortly after eight o’clock. Curfew was at ten o’clock, but long before that the streets were deserted. At ten o’clock two houses at Dillion’s Cross were set alight, and the adjacent roads were patrolled to prevent any attempts to extinguish the flames. Soon, petrol was brought into the city centre and various premises were set alight at random.

The fires spread rapidly and soon most of the southern side of St. Patrick’s Street was ablaze. Cork City Hall and the adjacent Andrew Carnegie Library were destroyed, with large tracts of Cork’s public and historic records destroyed forever. Between 1921 and 1930, St. Patrick’s Street was rebuilt in an early twentieth century style of architecture. Hence, two styles of architectures grace the streetscape, the northern side comprises the nineteenth century style whilst the southern side, comprises the early twentieth century style.

READ MORE HERE: 8. The Burning of Cork City, 1920 | Cork Heritage

Matters of Compensation, St Patrick’s Street:

Arising from the fall-out of the Burning of Cork, a committee was set up in Cork Corporation to engage and collect data and for the Westminster government, which was to be used in the compensation negotiations with the English government.

A total of £300,000 had been advanced for the reconstruction of St Patrick’s Street. The city solicitor noted that two investigators appointed by the Irish government and one by the British government had visited the city in the second week of August 1922. The British government representative was dealing with cases of damage done by their forces, which was the bulk of the damage in Cork City. He made a promise of a cash payment to the decree holder i.e. Cork Corporation.

Coupled with this mechanism and it appears to muddle the compensation package available, an international body called the Compensation Commission (the Shaw Commission) had been set up, which was appointed for the express purpose of, amongst other things, reviewing awards already made in the cases of criminal injury applications not defended by a city or county Council. Cork Corporation in mid-September 1922 was expecting the Shaw Commission to come to Cork. The minutes of the Corporation of Cork show the Council attempting to understand the two sources of compensation packages and the need to maximise any receipts of compensation packages.

Cork Corporation Council members pressed to harness the advance of £300,000 to provide much needed employment. An important decision was also taken to inform property owners within the destroyed area that the Corporation intended to enforce the byelaws with regard to the closure of temporary structures or timber walled shops. In the early part of 1921, they had emerged on the street and through good will from the Corporation had been allowed to stay but no legal right existed for their erection. A sub committee of the Corporation was to wait on the owners of property in the burnt-out areas who had submitted plans for reconstruction work. The Corporation urged them to proceed with work.

Subsequent to the Corporation’s plea, at a Council meeting, the councillors were informed that six firms in the burnt-out area were prepared to start rebuilding work. In several cases, traders informed the Corporation that tenders had been invited and in some cases, works had already started. The reality was that a large number of traders were not prepared to start. They were holding out to maximise any due compensation. Indeed, it was to take until 1927 when the elegant old Roches Stores building (now Debenhams) and the old Cashes Building (now Brown Thomas) were reconstructed.

LEARN MORE with Tom Spalding, Local Historian on the Reconstruction of St Patrick’s Street, 1920-1930:

VIEW: British Pathe’s view of St Patrick’s Street, 1927, Cash’s Buildings had just been re-built, following the building’s burning out in 1920,

Pana’a Golden Cinemas – The Savoy and Pavilion Cinema:

Two fine places of entertainment, two cinemas of high repute, the Savoy and the Pavillion adorned St. Patrick’s Street for much of the twentieth century.

The Pavilion Cinema opened on Thursday, the 10th March 1921 with a single presentation of DW Griffith’s epic, The Greatest Question. The interior was impressive, a plush 900 seater auditorium fitted with comfortable cushioned seats. The Tallon family from the Rochestown Road were owners of this new cinema, and Fred Harford was the first manager. It was the finest cinema in the city with an extensive orchestral music area to accompany the silent films. The ‘Talkies’ made their debut on Monday, the 5th August with an Al Jolson film, The Singing Fool. The film caused a huge stir in Cork and drew in 12,000 people in the first five days alone. The ‘Pav’ had a contract to show all the MGM films. The auditorium also had a stage on which live shows, recitals and concerts were frequently held to great popular acclaim.

On 16 February 1930, disaster struck when a fire swept through the building. The Pavilion was severely gutted. It reopened, fully remodelled and redecorated the following June. The building also possessed a fashionable restaurant and was always a suitable place to take a first date. The restaurant was often used for workshops during the Film Festival. Spiralling costs led to the closure of the famous restaurant in 1985. The Pavilion closed in August of 1989 with a screening of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade as its final film.

READ: Colette’s Sheridan’s, “Let’s reel in the years to cinema days of yore”,

Let’s reel in the years to cinema days of yore (echolive.ie)

The Savoy Cinema:

The Savoy Cinema was constructed in the early 1930s, was commissioned by the Rank Organisation, and was built by the firm of Meagher and Hayes. The first film was shown on Thursday, 12 May 1932. The cinema had a colourful art deco exterior with an imposing exterior lighted canopy. The interior design was elaborate with a spacious marble foyer. The rear of the Grand Circle was known as the Gods, which was the cheapest part of the house. The grand auditorium held an audience of 2,249 patrons. The Studios of Rank, United Artists, 20th Century Fox and Columbia supplied new films to the Savoy and the programme changed twice a week on Sundays and Wednesdays.

Sunday was always “the” night of the week to go to the pictures. The general public dressed in their best clothes. Fred Bridgeman, was the organist, and was the Savoy’s top live entertainer for nearly thirty years. The Cork Film International Festival, originally called ‘An Tostal’, began in 1953. For one week each year, the Savoy was home to the festival. By 1970, the character of the Savoy was starting to fade. The departure of Fred Bridgeman signalled the end of the era of the cinema organ and the grand sing-a-long shows. In 1975, the Savoy cinema closed. Today, part of the Savoy is a shopping centre and the remainder is awaiting redevelopment.

READ: Nostalgia: Glory days of Savoy Cinema remembered, Nostalgia: Glory days of Savoy Cinema remembered (echolive.ie)

WATCH: Dermot Mullane reports for RTÉ News on the final night at the Savoy as people left the cinema, the neon sign was switched off, and the doors were closed for the last time,

RTÉ Archives | Arts and Culture | Savoy Cinema in Cork Closes (rte.ie)

Former Savoy Cinema, St Patrick’s Street, present day (picture: Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

A Place for Every Creature – Seamus Murphy’s Dog Trough:

Beneath the pavement outside no 121 St Patrick’s Street, tucked in against the front wall is a little drinking trough for dogs. The trough is of Cork limestone and is just over 60cms in length, with the word Madraí (Irish for dogs) carved in an elegant Gaelic script on its front. The drinking trough was commissioned c.1960 from the Cork sculptor Seamus Murphy by Mr. Kenny Stokes when the premises was the Milk Bar, one of Cork’s most favoured tea-rooms of the 1950s.

Born near Burnfort, County Cork in 1907, Seamus Murphy was one of the foremost stone carvers and sculptors of his time. From 1922 until 1930 he worked as an apprentice stone carver at O’Connell’s Art Marble Works in Blackpool, Cork. He received a scholarship in 1931, which enabled him to go to Paris where he was a student at Academic Colarossi and studied with the Irish-American sculptor, Andrew O’Connor. After returning to Ireland, Seamus worked in O’Connell’s stone yard. In 1934, he opened his own studio at Blackpool. Among his first commissions were the Dripsey Ambush Memorial and the Clonmult memorial at Midleton, two statues for Bantry church and a carved figure of St Gobnait in Ballyvourney graveyard.

The Virgin of the Twilight was exhibited at the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1944, and was later erected at Fitzgerald’s Park, Cork. In 1939 he exhibited at the World Fair, New York. In 1944 he was elected Associate of RHA. That same year he married Maighread Higgins, daughter of Cork sculptor Joseph Higgins. In 1945 Seamus designed Blackpool Church for William Dwyer and in 1948 he carved the Apostles and St. Brigid for a church in San Francisco. Another of his sculptures is in St Paul’s, Minnesota. He was made a full member of the RHA in 1954. He became professor of sculpture at the RHA in 1964, and was awarded an Hon. LLD. by the National University of Ireland in 1969.

WATCH: Documentary marking the directorial debut of Academy-Award nominated filmmaker Louis Marcus, is a luminous portrait of renowned Cork sculptor, Seamus Murphy (RHA), The Silent Art – IFI Player

FOLLOW the Seamus Murphy History Trail: History Trail, Seamus Murphy, Cork Sculptor | Cork Heritage

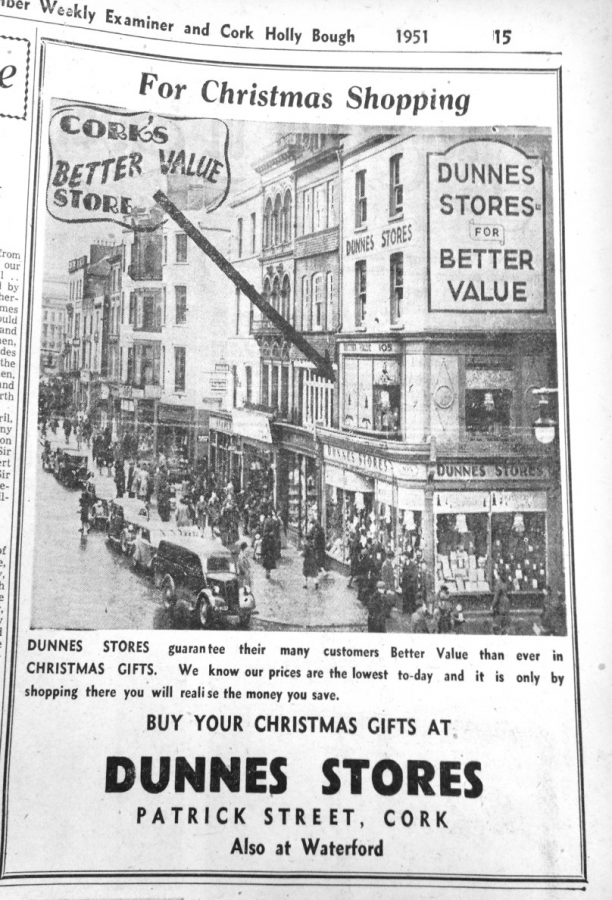

Dunne’s Stores:

Born in 1908, in the Co Down village of Rostrevor, Ben Dunne was in his late 20s when he moved to Cork to become a buyer with Roche’s Stores, the city’s largest retail outlet. A few years later he bought a vacant property at 105 Patrick’s Street, where he set up his first drapery shop. On opening day, 30 March, 1944, long queues began to form outside the city centre store from early morning. Ben Dunne opened his second drapery shop on Cork’s North Main Street two years later. That was quickly followed by new stores at Waterford, Mallow, Limerick, Wexford and at Dublin’s Henry Street.

In June 1961, Cork’s first fruit and grocery supermarket was established at Dunne’s Patrick’s Street store. Five years later, Dunne opened the country’s first out-of-town shopping centre in the Dublin suburb of Cornelscourt. He and his Midleton-born wife Nora Moloney had lived at Ringmahon House in Mahon, Cork for years, but the couple moved to Dublin after their land was acquired by Cork Corporation. After Ben Dunne died in Dublin in 1983 his supermarket empire passed on to his six children.

In 2008-09 the original supermarket at 105 Patrick’s Street was demolished to make way for a €35 million redevelopment, The frontage of the old shop was retained and incorporated into a new six-storey building.

READ MORE: Colette Sheridan’s article entitled “Dunnes marks 75 years in Cork”,

Dunnes marks 75 years in Cork (echolive.ie)

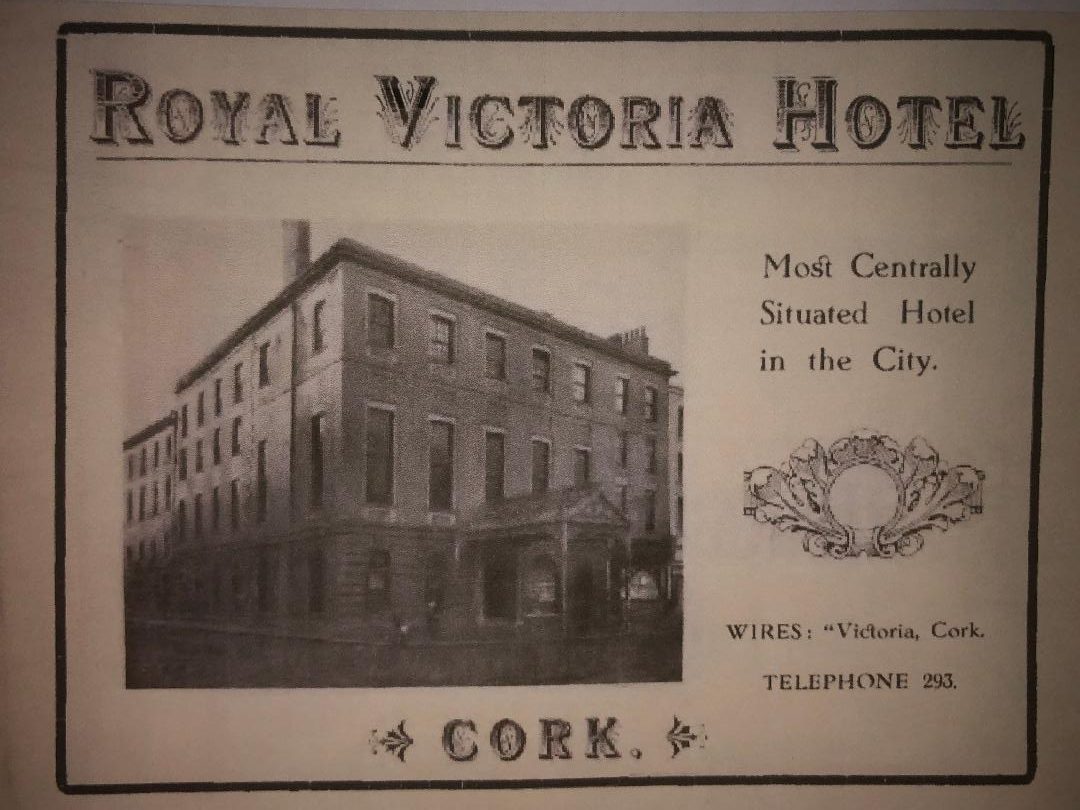

The Victoria Hotel:

The Cork Chamber of Commerce wished to have its own property and on 25 March 1831 two leases of property were taken out. One lease was for 479 years – the premises being described in the lease as containing 35 feet in front, 35 feet in width at the rear and 67 ½ feet from St Patrick’s Street down Cook Street. The other lease was for 649 years and was described as the ground on which the dwelling house of Catherine Anne Barrett stood and also its back yard and back kitchen. From 1834 onwards, the Chamber built a hotel and reading room at the corner of Marlboro Street and 104 St Patrick’s Street under a trust deed led by James Daly, Thomas Lyons, Charles Sugrue and various shareholders. The sum of £3,320 was subscribed by 99 merchants who were allotted shares to the number of 120 – the values of the shares being either £25 or £30. In addition to the capital outlay the first clause in the trust deed of 1836 runs to pay the treasurer an appropriate yearly fee of £1 10s.

The overall Chamber building facing onto St Patrick’s Street was a plain unornamental building, faced with cut limestone. Its reading room was described as a spacious apartment. The lower portion of the building was let into shops, and the rere was occupied as a Hotel.

In 1838, the Chamber of Commerce Hotel was renamed the Royal Victoria Hotel, on the occasion of the accession of Queen Victoria to the throne by Mr Thomas McCormick, senior. The Royal Victoria was patronised by the Royal Families of England, France, and Prussia, by the Grand Duke and Duchess of Saxe Coburg and Gotha, his Royal Highness Prince Phillippe, the Princesses Amelia and Clotilda, and other Royal personages.

Today the former Victoria Hotel awaits redevelopment.

The Second GAA Meeting in Cork:

In the late nineteenth century Gaelic games represented everything Irish and represented a cultural entity that was passed down through time empowering each generation. The idea for the GAA was posed by Michael Cusack who was born in Carron, County Clare in 1847. A fascinating and complex personality, his passion for Gaelic games was matched only by his love of teaching. After nearly twenty years experience in different schools he set up his own academy at 4 Gardiner’s Place in Dublin in 1878. He also had a huge active interest in athletics. In 1879, he was the All Ireland champion at putting the 16 pound shot and again in 1882. He deemed that athletic contests needed to encompass more people than just the gentry, the military and the middle class. He saw artisans and labourers excluded.

In 1884 Michael Cusack began the task of building an association that would represent his ideas. He approached a number of individuals who he felt would add to his cause. Archbishop Thomas Croke of Caiseal was a strong supporter of Irish nationalism. Croke had aligned himself with the Irish National Land League during the Land War, and with the chairman of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Charles Stewart Parnell.

Maurice Davin, another ally that Michael Cusack recruited, was an outstanding athlete who won international fame in the 1870s when he held numerous world records for running, hurdling, jumping and weight-throwing. He was actively campaigning for a body to control Irish athletics from 1877. He gave his support to Cusack’s campaign from the summer of 1884.

The proposed name for Cusack’s new organisation was the Munster Athletic Club. The first meeting was initially supposed to be in Cork. Hurling was fairly widely played around Cork City at the time, with teams such as St Finbarrs, Blackrock, Ballygarvan, Ballinhassig and Cloghroe in regular opposition in challenge contests. However, due to its central Ireland location, Thurles was chosen and also a new name came to fruition, the Gaelic Athletic Association. The meeting was held on 1 November 1884 with the object of reviving native pastimes such as hurling, football according to Irish rules, running, jumping, weight throwing and other Athletic pastimes of an Irish character, which were in danger of extinction

Those that attended the first meeting were Michael Cusack, Maurice Davin (who presided), John Wyse Power (Editor of the Leinster Leader), John McKay (journalist, Cork Examiner), T. K. Bracken (a builder from Templemore), P.J. Ryan (a solicitor from Callan) and Thomas St. George McCarthy (an athlete and member of the RIC).

Eleven days after the establishment of the GAA, the first Athletic meeting under the GAA was held in Toames, near Macroom.

A second meeting to help develop the ideas of the GAA was held in the Victoria Hotel, Cork, on 27 December 1884. In addition to Davitt, Cusack, McKay and Bracken, the following attended: J.J. O’Regan, John King, J.O’Callaghan, M.J. O’Callaghan, Dublin, W.J. Barry, W. Cotter, J.E. Kennedy, J.O’Connor, Dan Horgan, A.O’Driscoll, Cork, Dr Riordan, Cloyne. Alderman Paul Madden, the Mayor-elect of Cork, presided. The meeting had letters before it from Davitt, Parnell and Dr Croke accepting the invitations to become patrons. Through the following two years, rules for hurling, football, weight throwing, running, jumping and cycling were adopted.

John McKay, a journalist with the Irish Examiner, organised the first GAA sports meeting at Blarney on 3 May 1885. He followed it up with meetings at Ballygarvan and Killavullen an ever greater one in the Mardyke Cricket Grounds.

At the end of 1886, over 20 clubs, hurling and football joined the association – Cork Nationals, St. Finbarrs, Aghabullogue, Blarney, Ballygarvan, Ballyhea, Glanmire, Knockraha, Cobh, Carriganvar, Glandulane, Macroom, Midelton, Lisgools, Riverstown, Little Island, In addition, the Association in Cork was put on a more permanent footing in Cork when the Cork County Board was formed at a meeting held at 23 Maylor Street on 20 December. The first President was Alderman Dan Horgan of Lees Club.

The first County Championship game took place on 6 March 1887 at Cork Park. Clubs Lees and Emmetts played a scoreless draw. The Lees won the Replay. At the first County Convention held on 6 December 1887, representatives of 62 Clubs attended at the Mechanics Hall on Grattan Street. Since 1884, the GAA has grown and is very much rooted within places such as Cork.

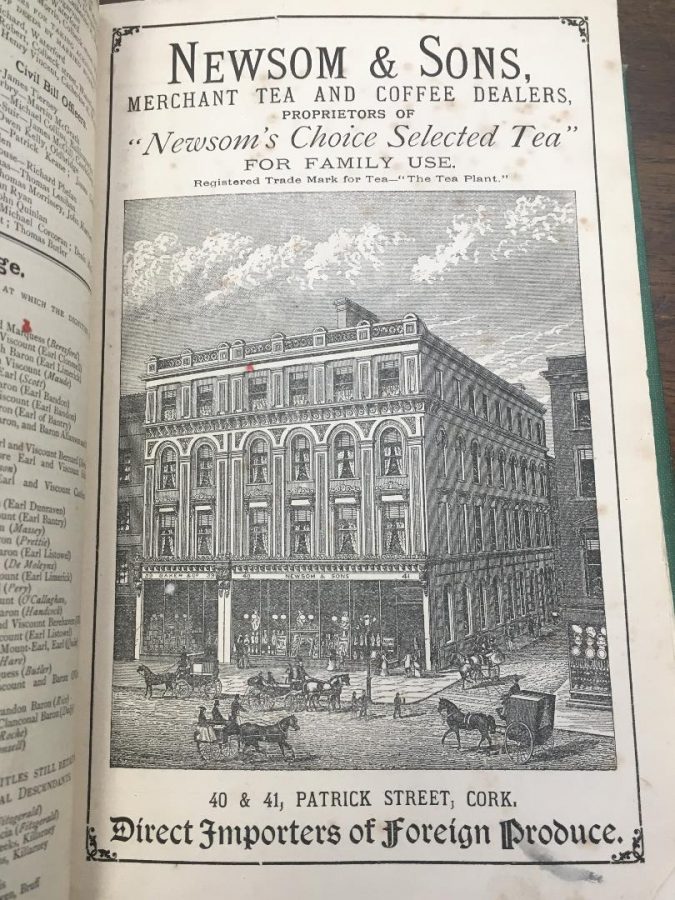

The Newsom Legacy:

The 25 January 1918 coincided with the news to Cork citizens that one of the its respected merchants had passed away – that of John Charles Newsom. The Cork Examiner records that at a meeting in the City Council Chamber in Cork City Hall Alderman Simcox proposed a vote of sympathy with the Newsom family of whose death they were all sorry to hear;

“The late Mr Newsom is a great loss to the commercial community in Cork. He was a member of many public boards, notably the North Infirmary. He gave lavishly to many of the charities in the city, and not only did he contribute to public charities, but he also gave privately. The poor of the city would deeply regret his loss, and frequently large crowds could be seen outside his place from year’s end to year’s end”.

The announcement of the death of John Charles Newsom took place at his residence Temple Lawn on Blackrock road. Born in 1838, he was a son of Samuel Newsom, and grandson of the founder of John Newsom and Son. In the wake of the Napoleonic wars and the consequent depression, Quaker merchant families began increasingly to concentrate on developing a new style business based on combinations of retailing and wholesaling. They took on insurance and shipping agencies and increasingly began to take on a rentier or landlord role. John Newsom set up his business circa 1816. His firm was situated at 109, St Patrick’s Street.

In the Cork Constitution, on 5 October 1830 it details some of the diverse products that John Newsom was importing – “100 casks of new mustard, 30 boxes of Kensington candles, Jamaica coffee in tierces and barrels, Double Berkley cheeses in baskets, fine salad oil in half-chests, Carolina rice in tierces, cotton and linen wick in bags, vinegar from Bordeaux, Zante currants, Italian liquorice, isinglass, citron and candy, pearl and Scotch barley, split peas, chocolate, patent and shell cocoa, wax and spermacetti candles”.

The Cork Examiner Site:

For generations, the Cork Examiner Office on Academy Street and fronting onto St Patrick’s Street was an important place to place an ad, meet a report or just to read newspapers. The site before the newspaper was called the Odd Fellows’ Hall. Then it became the Apollo Theatre and in 1841 the Cork Examiner was launched by John Francis Maguire.

On Maguire’s death, Thomas Crosbie took over the paper and made great strides in assembling a team of journalists, who tracked down their own stories. In 1892, a sister evening paper was launched in the guise of the Evening Echo (now The Echo).

In 1903 a modern printing was installed, using reinforced concrete for the first time in Cork.

In 1975 a large spring forward was made when computer technology replaced hot metal placing the Cork Examiner at the fore front of the industry in Ireland. With the advent of computerised printing, it became the first daily paper in Ireland to change to phototypesetting and web-offset.

The Cork Examiner became the Examiner in March 1996. Four years later that title was changed to the Irish Examiner.

To facilitate the redevelopment of the Opera Lane retail complex, in 2006 the Irish Examiner and Evening Echo offices moved to Lapps Quay. In recent years the staff of the two newspapers have moved to offices in Blackpool, Cork.

VIEW Jennie O’Sullivan’s news piece on the Irish Examiner’s last days at Academy Street, Cork

T W Murrays & Co:

The premises was established in 1828 and the shop has traded in everything from Explosives to Children’s toys. The O’Connell family took over ownership of the business in the 1920s when George O’Connell purchased the premises having managed it for many years. continue to offer a diverse range of goods, from our core range of Fishing and Shooting products to Hurleys, Darts, Pool cues, Peterson pipes, Zippo lighters, Leatherman, Victorinox knives and much more.

LEARN MORE: About Us – T.W. MURRAY & Co.

READ MORE: Michael Moynihan pays a visit to one of the longest surviving businesses on Cork main thoroughfare, Patrick Street, Michael Moynihan: From explosives to fishing – TW Murray and Co, almost 200 years of trading (irishexaminer.com)

Woodford Bourne Site:

In the mid nineteenth century, John Woodford had a grocery shop on the Grand Parade. Mr Woodford died during the Famine, and his widow married a Mr Bourne, an employee of Woodford’s and thereafter the firm was known as Woodford, Bourne & Co.

In 1869, Woodford Bourne purchased the supply of the wine merchant Richard Sainthill and extended the business to incorporate wines.

Woodford Bourne occupied one of the premier sites on the corner of Patrick Street and Grand Parade (currently MacDonald’s). The firm also owned extensive warehouse premises on Sheares Street.

James Adam Nicholson, who was an employee of the firm, eventually became the sole owner. For generations, the business continued in the Nicholson family until its subsequent sale in the 1980s.

In the 1980s, the shop was renovated to a fast-food outlet named ‘Mandy’s’ and the premises was taken over by MacDonald’s in the mid-1980s.

READ MORE: Home – Woodford Bourne Collection – UCC Library at University College Cork

Ends.