“Many of the scenes afford the finest subjects for the pencil and the pen; whilst in the bye-laws and more remote recessed, may yet be traced, manners, customs and opinions, but little changed, after the lapse of ages…every glen and hill-side still breathes of the stirring times when romance, and song, and deeds of high emprise influenced the habits and feelings of the people.

The wildest legends and lays, once poured forth by the bard or minstrel, are here deposited, cherished by a race whose great delight is in their recital. Monuments of the past, alike belonging to periods beyond the reach of history, or invested with associations derivable from names remarkable upon its pages, lie profusely scattered in every direction of the land here surveyed”.

Windele, J., 1846, Guide to the South of Ireland, Messrs. Bolster Cork. p. 2-3.

- This project is based on research carried out in the River Lee valley, County Cork (2006-2012) and published through my Our City, Our Town column in the Cork Independent.

- EXPLORE the articles here: 2006-2011 River Lee – In the Steps of St Finbarr | Cork Heritage

- Three books emerged from the project.

In the Steps of St Finbarre (NonSuch Ireland Press, 2006)

A book, which grew out my column in the Cork Independent, it focusses on the journey of the Lee and the key places of settlement, monuments and community leaders all the way along the valley. It contains lots of pictures and original material previously not drawn together (sold out).

Generations: Memories of the Lee Hydroelectric Scheme (co-written (Lilliput Press, 2008)

A book co-written with Seamus O’Donoughue, the work was published by the ESB to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Inniscarra Dam being commissioned. The work contains many pictures of the Lee Scheme being constructed and pictures of the ‘before and after’ of the affected landscape. It also profiles the positives and negatives of such an extensive venture for its day; buy it here: Lee Hydroelectric Scheme: Generations – The Lilliput Press

Inheritance, Heritage and Memory in the Lee Valley (History Press Ireland, 2010):

This book is based on the series of articles that featured in the Cork Independent newspaper from October 2007 to June 2009. It documents my explorations in the parishes of Aghabullogue, Inniscarra and Ovens on the northern valleyside on Inniscarra Reservoir, part of the course of the River Lee. It encompasses much fieldwork and oral history testimonies. The book is published by Nonsuch Ireland (sold out).

Extracts from In the Steps of St Finbarr, Voices and Memories of the River Lee Valley:

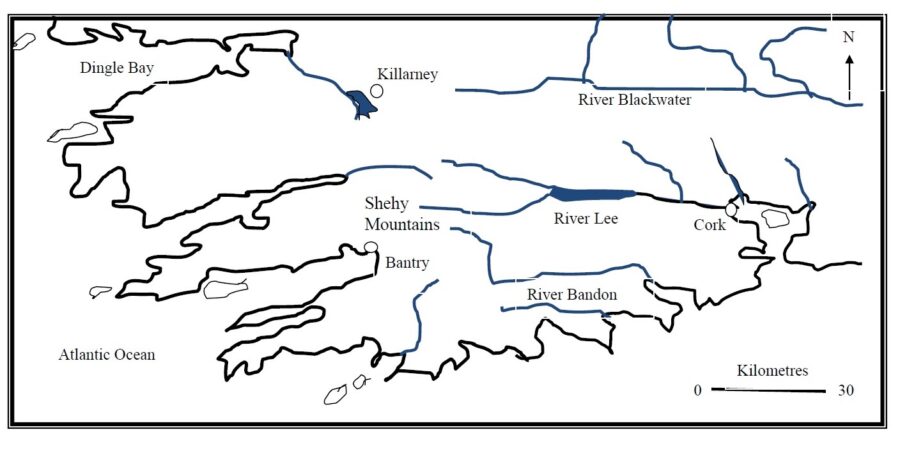

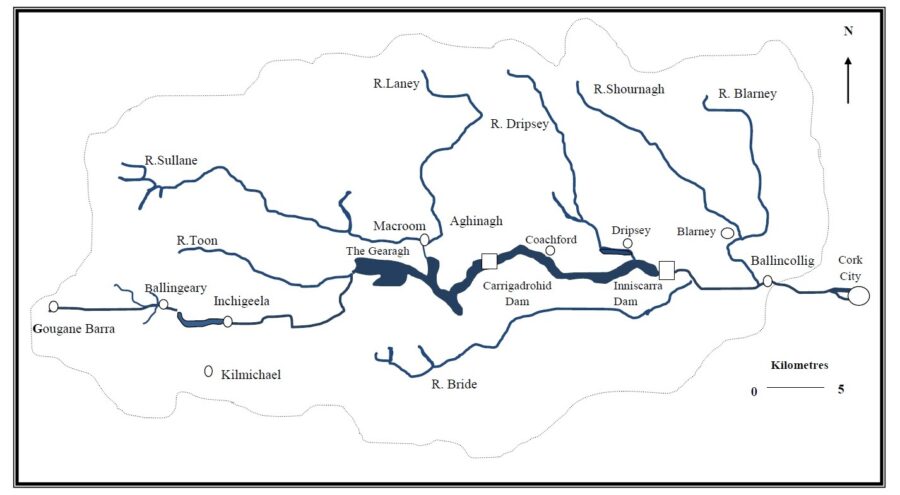

The area drained by the Rive Lee and its tributaries is about 400 square miles and has a number of tributaries. The principal drainage is from the north from the Derrynasaggert and Boggeragh Mountains whilst in the south the watershed is lower and supplies a lesser volume of drainage.

The Lee can also be divided up into three well-defined stretches, the first is the highland and foremost rugged section from Gougane Barra – its source area – to near Macroom. The second section is the immediate area affected by the Hydro Electric Scheme encompassing Carrigadroid and Inniscarra Reservoirs to where the river meets the tidal estuary at Cork City’s Lee Fields. The third section is the complex tidal estuary of Cork Harbour.

The Our City, Our Town River Lee articles focused on the first two sections and on the river’s immediate path and valleyside from source to Cork City.

The Lee Valley is one of the most beautiful landscapes in Ireland and echoes a human presence of over 5,000 years. The landscape provides memorable, panoramic to intimate views for the human eye, all woven together to create a tapestry of beauty. Ireland’s recent Celtic Tiger economy has brought unprecedented changes in society; it has brought affluence, immigration and a conflict of the global and the local. The Lee Valley has been affected by the architecture of the last century and twentieth-first century. The landscape has witnessed large-scale feats of engineering such as Inniscarra Dam and the associated reservoir to one-off housing. Contrasting all of that, the landscape is still essentially rural with a strong farming population.

The River Lee is an extension of city life. In a sense, the notion of a divide between town and country are merged. Places such as the Shehy Mountains or the pilgrim site of St. Finbarre’s Gougane Barra and Cork Harbour are connected. Indeed, the river for many of us Corkonians provides a link with times past and that a sense of civic pride. Many of us have crossed over the River’s bridges and have appreciated its tranquil hypnotic flow. It reflects vitality, engages the senses and presents a sense of mystery and secrecy. Despite the parapet walls, the River Lee is an accessible amenity that all can appreciate but for the most part in recent decades, we have largely ignored.

The geography of the visible River valley is fractured and diverse. It is a beautiful landscape, a landscape transformed through the centuries by people. The diverse archaeological monuments from Stone Age tombs to the solitary Norman or Irish castle to the nineteenth century churches reflect the use of the River Lee Valley and its scenery and resources by its residents for the nourishment of the soul, living and surviving. The townland names of the ordnance survey reflect a human story especially the impact of human history on the natural landscape. It is an impact, which spans thousands of years.

For the majority of us Corkonians, we see the River Lee as an inspirational feature in Cork life, one, which is sacred. It is a feature, which each successful generation of Corkonian is brought up to respect, just like our other sacred places such as the Lough and Fitzgerald’s Park. This work seeks to awaken an interest in the welfare of the River Lee Valley. The history and geography of the Valley is hidden and scattered along its sixty-kilometre journey from the Shehy Mountains to Cork City.

The articles are not a definitive work on the valley but are attempts to highlight, discover, appreciate and explore an area through the voices of visiting antiquarians, historical societies, Corkonians, locals, maps and panoramic images. This work investigates the relationships between people and place, which have created different landscapes within the River Lee Valley. It discusses the different meanings of the river for not only Cork people but also for those whose life journeys began elsewhere and who crossed and were inspired like myself by its flow and the human and natural landscapes it influences.

Moreover, the articles are my call to encourage all Corkonians to go out and explore our own lovely River Lee.

The Name of the Lee:

The origin of the name Lee is sketchy and legend reputedly attributes the name to an ethnic group known as the Milesians from Spain who reputedly arrived in Ireland several thousand years before the time of St. FinBarre. Legend has it that the Milesians acquired land in Southern Munster, which they named ‘Corca Luighe’ or ‘Cork of the Lee’ from Luighe, the son of Ith who attained the land after the Milesian advent to Ireland.

The River Lee – An Laoi over the centuries has had many variations in its spelling. In early Christian texts such as the Book of Lismore, it is described as Luae. It has also been written as Lua, Lai, Laoi and the Latin Luvius. An entry in the Annals of the Four Masters in the year 1163 A.D. names the River Sabhrann. However, many scholars agree on the name Lee as the most common name of the River.

Gougane Barra:

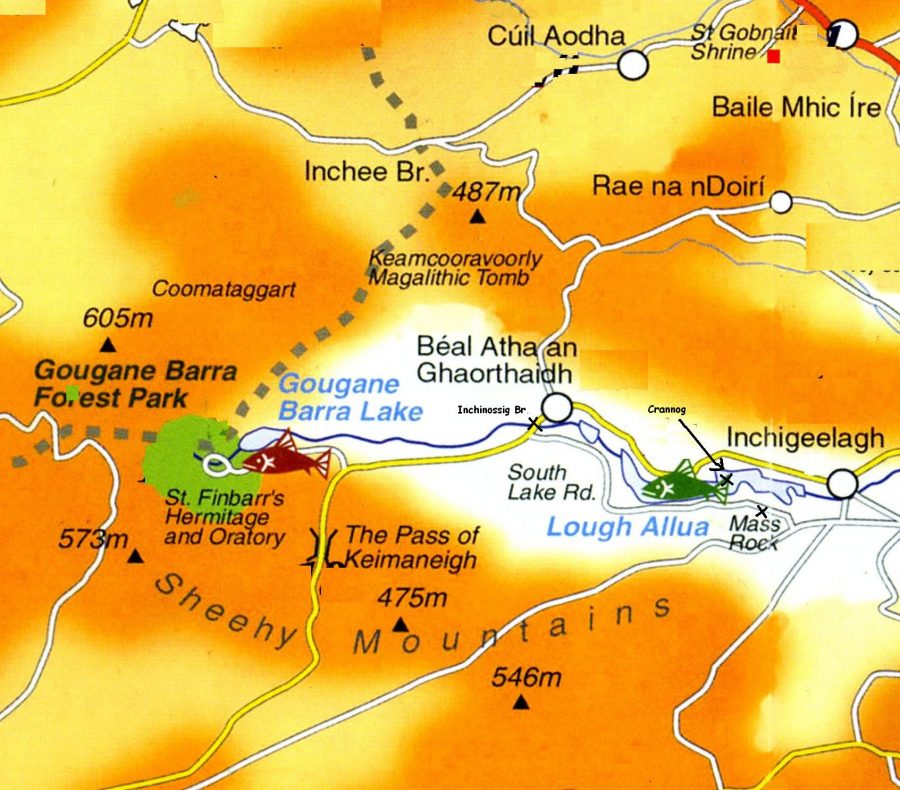

Irish folklore has it that the patron saint of Cork Finbarre was educated as a monk and hence established several churches in the Munster area. One of these monastic sites was located on a rocky island in the centre of a lake overlooked by the Shehy Mountains where the River Lee rises. Indeed, the name of this lake today reflects the latter; ‘Gougane Barra’ or ‘Finbarre’s rocky place’.

View Kieran’s A Stroll in Gougane Barra:

Centuries later, the original and reputed monastery of St Finbarre was to become ruinous and Fr. Denis O’ Mahony circa 1700 built a replica of it. The buildings that Fr O’Mahony built i.e. the Pilgrim’s Terrace and Church still survive and have been altered through time to preserve them.

Fr C M O’Brien’s book on the Life of St Finbarr, possibly published to coincide with the dedication of the oratory, seems to serve as some kind of official guidebook to the oratory. He notes that St Finbarre’s Oratory (built c.1900/01) owes its origin to the local parish priest Fr Patrick Hurley who financed the erection of it to two wealthy Irish Americans in America (one living in Chicago). The new oratory replaced Fr Denis O’Mahony’s near two-hundred-year-old ruinous oratory.

The design of the church is bound with the Gaelic revival of the late nineteenth century. That was a time when there was a resurgence of interest in engaging with the Gaelic language and ancient Irish folklore, sports, songs, architecture, and arts were considered to be part of the pre-English conquest heritage of the native Irish people. The oratory is built in Hiberno-Byzantine style and modelled after the Chapel of Cormac on the Rock of Cashel (begun in 1127 AD).

Mr Samuel F Hynes, Cork, designed St Finbarr’s Oratory and the artist was Mr M J C Buckley, Cork and Bruges, Belgium. Samuel F Hynes was part of a wider group of late nineteenth century architects employed to create new symbolism for the Catholic Church which was growing in strength since the sanctioning of the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829.

As for Michael J C Buckley, he was of Irish birth. He seems to have been in business on his own until around 1881 when he became a partner of Cox and Son. After the firm was bought out in the 1890s, Buckley appears to have returned to Ireland and continued to work. The walling is of mountain stone and is relieved by dressings of limestone, while the roof, like the Chapel of Cormac, was originally of stone, necessitated by the heavy rains that prevail in mountain districts. Rev C M O’Brien’s book Life of St Finbarrr (c.1901) notes that the western end of Gougane Oratory is ornamented by a boldly excised doorway of limestone, with hook shafts and caps and vases, the arches being enriched with chevron ornament. At the head of the label mould is a boldly cut head of St Finbarre. The original plan was to have a round tower at the entrance to the oratory, but it was never completed.

The Tailor and Ansty:

The various geographies or perhaps meanings for visitors of the Shehy Mountains and accounts by various visitors to Gougane Barra are multiple in nature. In 1941, one such visitor enthralled by the vistas of Gougane and the lives of its people, Eric Cross, wrote a series of articles in The Bell about two larger than life residents of Gougane, the Tailor, Tim Buckley and his wife Ansty (Anastasia). Eric Cross was born in Newry, County Down, in 1905 and was educated as a chemical engineer. With no direct connection with the Tailor and Ansty, he came across the couple on a holiday to West Cork in the late 1930s / early 1940s. His interest in human nature led him to come back to Gougane on several occasions and to interview the Tailor at length about his life.

In 1964, Eric Cross compiled a series of articles on the Tailor and published the work in 1964. Eric chose Cork writer Frank O’Connor to write the introduction, another lover of all that Gougane has to offer. It is clear from Eric Cross’s work, that he is attempting to describe a couple who symbolize the magic and culture of rural Ireland and of course maybe for us today indirectly explain why so many Cork people, Irish people and foreigners flock to or retreat to the sanctuary for holidays in West Cork.

In the Heart of Uíbh Laoghaoire:

“A little to the east of the island [Gougane] is the exit of the Lee. Its shallow bed is here crossed by a few stepping stones, shortly below which the stream is heard sounding wildly,

and its course seen impeded by rude masses of naked rock, standing out stubbornly, as if in resistance to its escape, or forming rough and irregular ledges, over which it is hurried, bounding deliriously from rock, to rock, and sweeping with headlong rapidity, chafed and all in foam” (Windele, 1846, p. 293).

Uíbh Laoghaire or in its English derivative, Iveleary, means the “Descendants of Laoghaire”, and is applied to the territory which they inhabited. Before the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland (1169 onwards), there were four great divisions in Cork County.

One of those divisions was Muscraidhe (Muskerry), which occupied the north of the county. Muskerry or Musc Raighe means the “Territory of Cairbre Musc”, a family of Celts, who lived in the area in the 3rd century A.D. Muscraidhe was sub-divided into three parts, one of which was called Muscraidhe Uí Fhloinn now the barony of West Muskerry containing fifteen parishes and extending to the borders of Kerry. As the name indicates the O’Flynns were the early lords of this territory, but its history is mainly associated with the MacCarthys.

The O’ Leary Country, formerly known as Tuath Ruis, was in the South of Cork County, a part of the present Diocese of Ross. Shortly after the Anglo-Norman Invasion, the O‘Learys were driven into the western part of Muscraidhe Uí Fhloinn and the district became known as Uibh Laoghaire. The term Uíbh Laoghaire is now understood to mean the district co-existing with the parish of Inchigeela in the west of Cork County. It may be said to comprise the basin of the River Lee from its source at Gougane Barra to halfway between the village of Inchigeela and the town of Macroom. The Lee runs from west to east through the district, and by far the greater part of Uíbh Laoghaire lies to the north of the river; the two chief villages being Inchigeela and Ballingeary.

Manoeuvres in Keimaneigh:

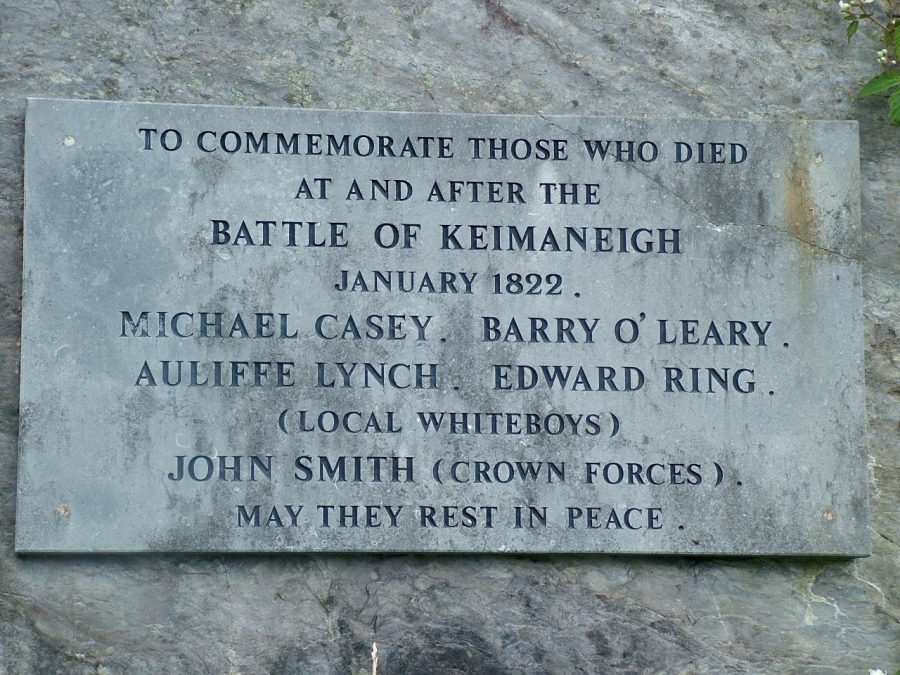

The Pass of Keimaneigh is by its very nature is a wild, rugged and natural boundary between the coastal regions of Bantry Bay in West Cork and the mountainous terrain, which encompasses areas such as Gougane Barra and upper River Lee valley. Over three kilometres long, the Pass originated as a melt water channel from a melting glacier, 20,000 years ago. On both sides of the Pass, are sheer cliffs rising each side to a height of 100 feet above the road. Today the Pass marks the official division between the small Irish-speaking area of the West Cork / Gaeltacht and the rest of the region. In centuries gone by, it was the dividing territorial line between the Gaelic Irish families of the O’Sullivans and O’Learys.

The mountain pass is immortalised by local poet Máire Bhuí Ní Laoire in her poem Cath Céim An Fhia, an account of a battle in 1822 between Local Whiteboys and Yeomen supported by British soldiers. A memorial exists in the middle of the pass, which recalls the conflict It was economics not politics, which determined the historic but tragic events. The Irish tenant farmer and the labourer experienced much economic hardship in 1810 and 1820s. A change in political system, nearly 180 years previously (1640s), had meant that many Irish landlords, who chose not to be loyal to English government, had their lands dispossessed and handed over to English gentry. The ensuing landlord systems, which strengthened and evolved in the eighteenth century, created rent increases for tenants and subsequent evictions for non-payment (O’Leary, 1995).

Of the many movements established across Ireland, who resisted any injustice, were secret societies such as the Whiteboys, who operated at night carrying out raids against their persecutors. After the Napoleonic War between England and France finished in 1815, a downturn in the economy meant conditions became worse. There was a serious economic depression across the British Empire. West Cork was severely hit by the near end of the lucrative trade of supplying ships with butter and other provisions in Cork Harbour.

Ballingeary Village:

Ballingeary Village or Béal Átha an Ghaorthaidh (ford mouth of the wooded glen) is located partly in the townland of Kilmore (Choill Mhór- large wood) and partly in Dromanallig (Drom An Alligh – ‘Ridge of the Rocky Place’). The village is divided by the River Bunsheelin, which joins the River Lee just to the east of the village.

The Discovery Series Ordnance Survey map of the landscape shows some insights into the history of the Ballingeary area but this is very much a place that to be understood must be traversed and visualised. Inchinossig Bridge is the first bridge that the River flows under on its journey to Cork Harbour. The anglicised version of the term ‘Inchinossig’ is Inse an Fhosaigh, which means ‘Level Spot of the Encampment’, which refers to local folklore that the area was once used as a staging point of attack or maybe attacks. It is not known what period of time the name refers to or who. Whether or which, there was possibly a causeway to provide a crossing across the River Lee, which since Gougane Barra, has now been fed by its first tributary, the Owengarrrif River.

Crossing points of rivers usually create associated settlements. Further downstream lies Dromanallig Clapper Bridge, a stone causeway, which appears old and without doubt predates the Inchinossig structure. It comprises 32 slabs of various sizes supported by stone piers. In 1987, when the river was deepened upstream, a number of slabs collapsed. Today fourteen original slabs remain insitu. The present day Inchinossig Bridge dates to the 1820s and probably was part of a general scheme of developments that took place across Ireland at the time. Bunsheelin Bridge in Ballingeary Village also dates to this time. Substantial Westminster funding was invested in Imperial infrastructure such as new roads, bridges and architecture in the 1820s. The funding was dispersed through all parts of the Empire by the decisions of local Grand Juries who comprised local landlords and magistrates.

At the eastern entrance to the village stands Coláiste na Mumhan, which was opened on the 4th July 1904 to cultivate young students in the Irish language and culture. Over one hundred years later, this college successfully every summer plays host to over four hundred students, who converge on Ballingeary for set periods of time. On it walls facing the road is a plaque highlighting past supporters of the College and noting their role in the Irish war of Independence, which includes Cork City patriots Tomas MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney.

Further along the eastern road into Ballingeary Village lies the artefact of the Famine Pot. As an aftermath of the Irish Great Famine of the mid 1800s, the population of the Parish of Iveleary decreased by more than a quarter. The population in 1841 was 6,357 with 1.032 cabins. By 1851, 231 cabins had been vacated and the population stood at 4,584. A soup kitchen was established in the nearby townland of Coolmountain House, through the efforts of relief committee headed up by Parish priest, Fr. Jeremiah Holland, Rev. Sadleir and the occupier of the House and associated farm, Denis O’Leary. The famine pot is a reminder to those dark days in rural Ireland.

At the entrance to the western side of the village lies Casadh na Spríde, a man made garden, built in 1998 and dedicated to the memory of the O’Sullivan clan who retreated from their winter battle with the English in the Beara Pennisula in the winter of 1601. On New Years Eve 1602, Donal O’Sullivan Beara and his 1000 followers passed through Ballingeary on their celebrated forced retreat from their home on the Beara Peninsula to Co. Leitrim. They camped at Teampaillín Eachrois, a ruined church two miles north of Ballingeary. At the end of their two-week ordeal only 35 reached their destination in O’Rourke’s Castle in Leitrim Village. The Central interpretative plaque in Casadh na Spride notes that the garden was made using local timber and feature native flowers and plants.

View Kieran’s “Exploring Ballingeary, Co. Cork”:

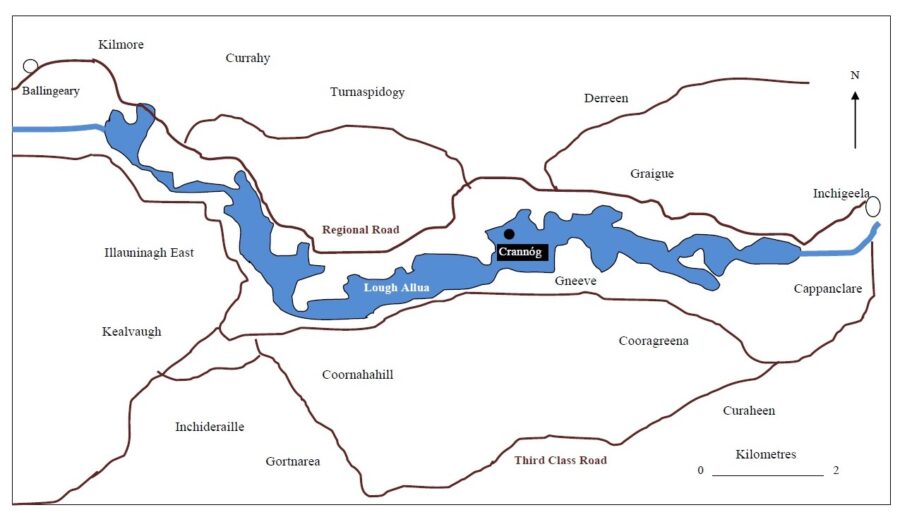

Wonders of Lough Allua:

Lough Allua on any day is a feature to behold and is such a contrast to the overbearing Shehy Mountains in the distance. One now gets the sense of the River Lee’s movement and journey towards its mouth especially with its maturing torrent. Lough Allua between Ballingeary and Inchigeela in West Cork conjures up many emotions for the visitor. Despite the encroaching ‘bungalow blitz’ culture along the shoreline of the lake, Lough Allua seems to have carved a niche into the local geology.

The surrounding landscape conveys all kinds of messages to the visitor but not in an obvious way. To get a feel for Lough Allua, you have to circumnavigate it and/or boat across it. The topography of Lough Allua does have that sense of wilderness with enjoyable scenery for the visitor and for the modern bungalow owner and then all that contrasted against the local habitats for wildlife and fowl.

There is evidence that at least communities were settling in the lake area as early as the Bronze Age in Irish Prehistory (c.2,500 B.C.). Here on the northern valleyside of Lough Allua, in the townland of Currahy, a standing stone and a stone row stand as markers of communities of the latter age of prehistory. The standing stone is located on the shoreline of the lake, perhaps symbolising control and power by its one-time Bronze Age residents over the area.

A clump of trees in Lough Allua reveals evidence of an early medieval settlement (c.800 A.D.) in the form of a crannóg. A crannóg, which means a “small island built with young trees”, is an artificial circular or oval island, which was constructed in lakes. In general, they were built of dumped layers of brushwood, timbers, stone, soil and peat. A palisade or fence or vertical timbers encompassed many sites. Access to crannógs was via stepping-stones or bridge or by boat. In general, they were built in an area of shallow water within easy reach of the shore (O’Sullivan, 2000).

There are at least 1,200 known crannóg sites in Ireland with their distribution encompassing mostly small lakelands in the north west and north east.

Inchigeela Narratives:

The River Lee emerges at the eastern end of Lough Allua and continues on its journey. Next up is Inchigeelagh, the unofficial capital of the Parish of Uíbh Laoghaire. Inchigeela, a settlement, which straddles the River Lee. It is said to have got its name from its Irish derivative Inse Geimhleach or ‘The Island of the Hostages’. Local folklore tells of an incident several centuries ago when the O’Leary’s took some Danes hostage on the island, which is now the River Island Amenity Park. The Danes were called Macoitir and their descendants today are the Cotters.

The O’Leary family name has never left Inchigeela. It is O’Leary homeland, the family is connected and rooted to the place. Today, the O’Learys are sub-divided into sub-septs across the world. Every year, local men Peter O’Leary, Joe Creedon and Eugene O’Leary organise an annual O’Leary Clan Gathering, where members come from the four corners of the world to celebrate the family’s heritage. Exploring the main village graveyard, which was opened in 1925, there are numerous other family surnames, who have also shaped the life of Inchigeela i.e. O’Sullivans, Moynihans, McCarthys, O’Sheas, Murphys, Lyons, Creedons, Creeds, Luceys, O’Callaghans, Mannings, Kellehers, Buckleys, Healys and Oldhams.

Creedon’s Hotel is like the ‘city hall’ of Inchigeela. Its proprietor Joe Creedon is a man who is clearly proud of the history of this West Cork location. The lounge is a quaint space but here the history of the Creedon family is displayed, Cork’s G.A.A. wins are remembered, the Irish War of Independence in the context of Tom Barry and the Flying Columns are highlighted and Joe’s love for art are all displayed. Joe Creedon describes Inchigeela as “a curiosity town, an inspiring place….a beautiful woman…a

muse…a world of its own …and connected to place”. Joe is one of nine brothers and four sisters. His brothers John and Conal are well known for their broadcasting and literary works respectively.

Joe, like a Mayor of Inchigeela, is well connected to his local place. His interests are varied, a local school heritage programme, the annual O’Leary Clan gathering, the local Farmers Market and the Daniel Corkery Summer School. Lectures, music art, exhibition and workshops on aspects of Irish history are the summer school’s content. Joe notes that cultural tourism is not a new concept in the village and highlights the work of Bord Fáilte in the 1950s and 1960s promoting West Cork and locations such as Inchigeela.

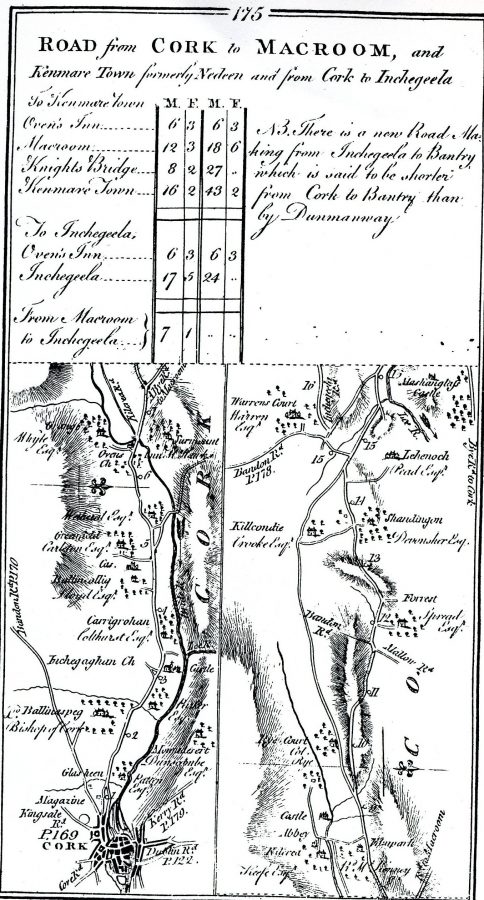

Creedon’s Hotel is perhaps one of the oldest licensed premises in County Cork dating to before 1800. The development of local roads by Grand Juries meant that Creedon’s Hotel was once a Coaching Inn based on a main road, which ran from Cork to Bantry. The Lake Hotel across the road from Creedons was established in 1810 and is also testament to the fact that there have always been people passing through the area.

View “Exploring Inchigeela, Co. Cork by Kieran McCarthy”:

Times Passes – Religion, Education and Inchigeela:

Two of the most noticeable features in Inchigeela is the Catholic Church and the ruins of the Protestant church with their respective graveyards and both of which are situated on the northern bank of the River Lee. These cemeteries have served the Parish of Uíbh Laoghaire for over 300 years and have used by parishioners of all creeds.

The first reference to Inchigeela Parish is in a Vatican record in 1492, the year Columbus sailed for the Americas. Local folklore notes that the church was probably in existence before the fifteenth century. The parish was and still is in the Diocese of Cork. During King Henry VIII’s reformation period in the mid 1500s, all parish churches were confiscated and allocated to the established Protestant Church. It took many years for this change to reach rural areas such as Inchigeela as local chieftains, the O’Learys and their followers stayed with their Catholic religion.

O’Leary Homeland – Carrignacurra Castle:

Just two miles east of Inichigeela on the River Lee lys a physical and early realisation of revolution and the protection of this West Cork homeland in the form of Carrigacurra Castle. This is the first castle to be met with on the river. Built atop a rock outcrop, the name Carrignacurra or Carraig na Corra means ‘the Rock of the Weir’. It is believed that an eel weir was located immediately below the high rock on which the castle or to be more correct the tower house now stands. This was the principal seat of the O’Leary’s in Uíbh Laoghaire. The other two O’Leary castles in the neighbourhood were Carrignaneela and Drumcarra just east along the River Lee valley. Nature provided an ideal moat with almost impenetrable mountains, rocks and bog in the surrounding landscape.

Echoes of the Past at Kilbarry:

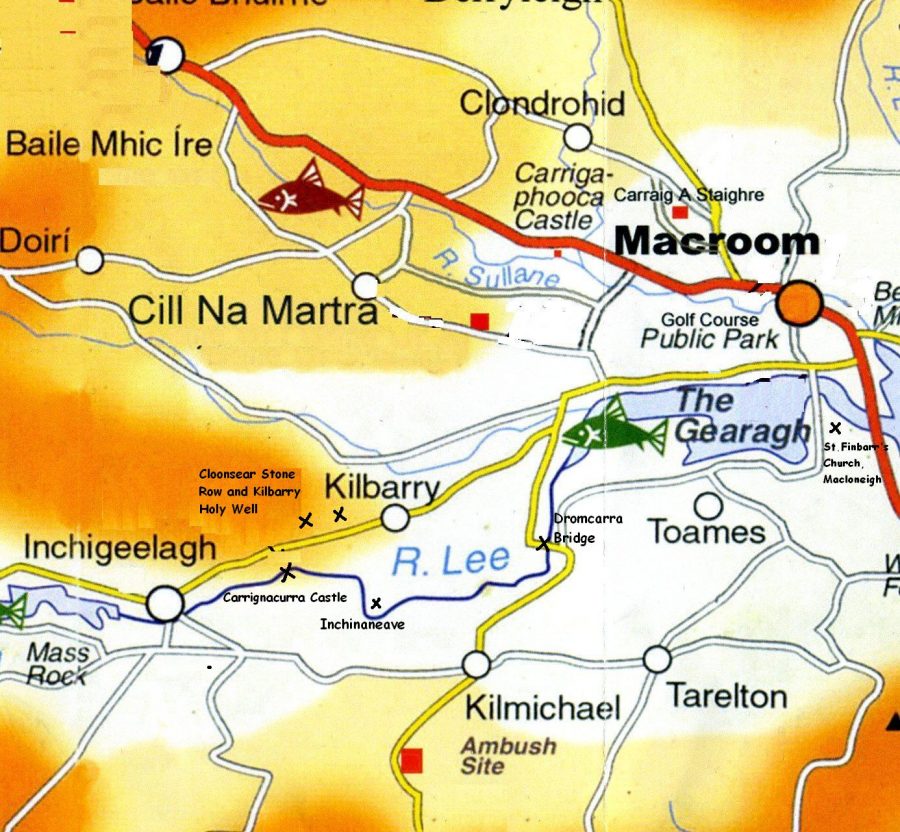

I was drawn to Kilbarry because of its name, Cill Barra or the Church of Barry, a place named after St. Finbarre. Here was a connection, another link to the fabled walk of Cork’s patron saint walking from Gougane to the Cork harbour. Kilbarry is on the main road from Macroom to Inchigeelagh, another small settlement but with an intriguing past.

The old and ruined Kilbarry Church is situated on a terrace, in pasture, near the summit of Kilbarry Hill in the townland of Carrignaneelagh. On the map it is noted as “Burial Ground”. The site overlooks two river valleys that of the River Lee and the River Toon (which joins the Lee at the Gearagh) and lys for the most part I the adjacent parish of Kilnamartyr. It is said Kilbarry Church was a chapel of ease to Inchigeela built by the O’Learys and probably was contemporary with the O’Leary Castles in the area in the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries (A.D.). In 1700, the Protestant Bishop of Cork, Dive Downes in his travels described the ruins as “walls of a church or chapel, called Killbarry, the walls built with stone or clay are standing uncovered” (Power, 1995, p.379).

The present day ruins are rectangular and grass and sod-covered throughout. The lower courses of the western wall with its rubble masonry can be clearly seen. The southern wall has become incorporated into the roadside fence. There is no visible surface trace of the churchyard or burial ground with burial markers, even though the local parish priest through the years blesses the site on occasion.

Kilmichael Ambush Memorial:

The Kilmichael ambush site was one of several staging points of attack on British forces during the Irish War of Independence. On 28 November 1920, the Black and Tans left the town of Macroom, to be unexpectedly greeted by the Flying Column led by West Cork man and republican Tom Barry at Kilmichael. Tom had enlisted in the British Army during the First World War and served in Mesopotamia. He returned to Ireland in 1919 and became a prominent member of the Irish Republican Army during the War of Independence. The ambush area he chose was and still is in the centre of a rocky and barren landscape. A week before the ambush, men came together at nearby Clogher to be trained in guerrilla warfare tactics by General Barry.

In all seventy-five men were involved in the Kilmichael Ambush and they were from all parts of West Cork, including Dunmanway, Clonakilty, Bantry, Bandon, Ballineen, Newcestown and Coppeen. Tom Barry later penned Guerilla Days in Ireland (1949) and The Reality of the Anglo-Irish War 1919-21 (1974), which detail his own memories and perspectives on and personal role in the Irish War of Independence. In Guerilla Days in Ireland, he noted of his tactics at Kilmichael:

The point of this road chosen for the attack was one and half miles south of Kilmichael. Here the north-south road surprisingly turns west-east for one hundred and fifty yards and then resumes its north-south direction. There were no ditches on either side of the road but a number of scattered rocky eminences of varying sizes. No house was visible except one, one hundred and fifty yards south of the road at the western entrance to the position. It was on this stretch of road it was hoped to attack the auxiliaries.

As the first lorry of Black and Tans came around the turn of the road, Tom Barry, dressed in a volunteer tunic, stood facing it on the road. Because of the fading light, the British thought him to be a British Officer and slowed down. As they did, Barry blew on his whistle and tossed the mill bomb, which landed in the lorry killing the driver. The No. 1 Section dealt with those remaining in the lorry, the Auxiliaries firing shots and the Flying Column pouring lead into them. Soon, some of the Auxiliaries were on the road, the fight becoming a hand-to-hand one. The Auxiliaries in the second lorry were taken on by the No. 2 Section and soon, those in the first lorry had been defeated. Seeing this, Barry and his three companions moved along the grass verge from their post to ambush the second lorry from behind unknown to the Black and Tans.

The Kilmichael Ambush delivered a ‘profound shock’ to the British system, happening only a week after the ‘Bloody Sunday’ assassination of a dozen army officers in Dublin and days after a large section of the Liverpool docklands was burned down. Dublin and Liverpool showed British weaknesses, but Kilmichael revealed that the IRA could combat and win against British soldiers in the field. Shortly afterwards a small memorial cross was erected at the Kilmichael Ambush site.

Fast forwards to 1966, and across the country, various groups chose to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the 1916 Rising through various means such as parades and unveiling new memorials. Cork had the highest number of events with thirty-four recorded events.

Cork’s Southern Star newspaper (on 5 February 1966) noted that to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising in the Kilmichael area, in January 1965 a committee had begun working a year earlier on a new monument for the ambush site. The committee was headed up by its president, Commandant General Tom Barry (veteran leader of the ambush).

On 10 July 1966 Canon Cornelius O’Brien, Parish Priest of Kilmichael, unveiled the elaborate monument, dedicated to the memory of the Kilmichael Ambush in 1920. It was completed by Terry McCarthy, of McCarthy and Sons Sculptors, Cork City.

View Kieran’s Exploring Kilmichael Ambush Memorial short film:

The Gearagh:

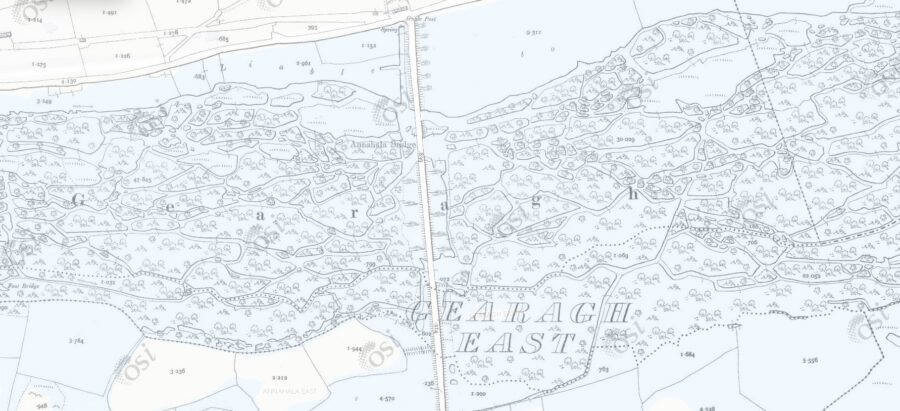

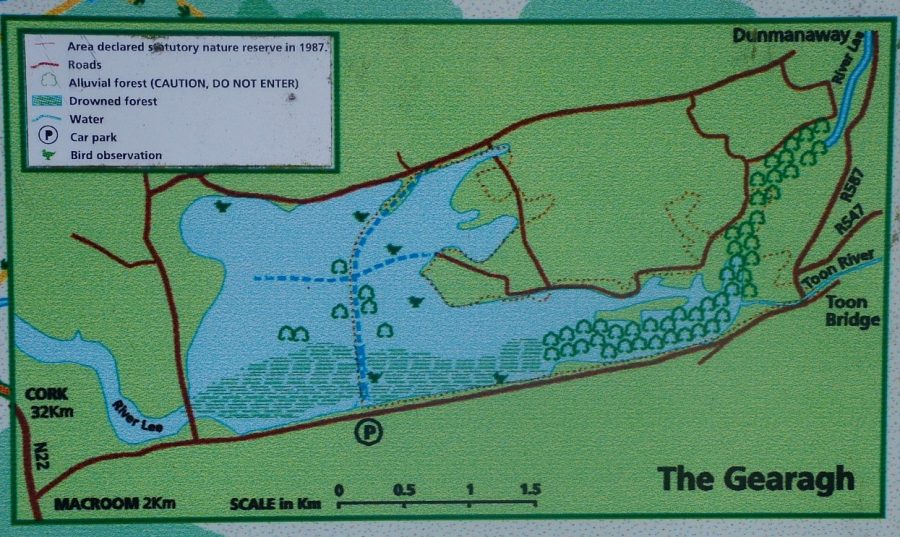

One of the areas most significantly influenced by the Lee Hydro-Electric Scheme of the 1950s was the Gearagh, an area, which extends eastwards and southwards from Dromcarra Bridge and then about seven kilometres to the Lee Bridge. Charles Smith, antiquarian, in 1750 noted:

“This river has its course here, interrupted with islands and a deep boggy tract, until it runs to the bridge of Ballynaclassen. These islands are covered, mostly with oak, ash, hazel and birch; at the feet of which grow fern, polypodium, and water drop worth. Here are great quantities of several kinds of water fowl, in their season, as bitterns, cranes, duck and mallard, teal, &c.. These bogs have been attempted to be drained, but it was found impracticable. In one called Anaghaly, is about three acres of ground, on which is excellent limestone, that supplies the town of Macroom, the western inhabitants of this barony and Carbery, with lime for manure and building” (Smith, 1750, p.190).

The Lee Hydro Electric Scheme destroyed half the original area of the Gearagh. Despite this, today, the area represents the only extensive alluvial woodland in Ireland or Britain, or indeed Western Europe west of the Rhine. For this reason it is a unique site and has been designated as a Statutory Nature Reserve. The Gearagh qualifies as a priority habitat under Annex I of the European Habitats Directive. The international importance of the site is recognised by its designation both as a Ramsar site or a United Nations Area of Conservation and as a biogenetic reserve. The adjacent reservoir is also a Wildfowl Sanctuary (Dept. of Marine and Natural Resources, 2006).

The wooded part of the Gearagh is largely undisturbed due to the inaccessible nature of the terrain. Annahala Bridge provides a bridge into this special site. Annahala, the townland east of Teerqay or Eanaigh Gheala means white marshes, a name linked to the adjacent outcroppings of limestone and the worked quarry, which was filled in during the flooding of the area for the Lee scheme.

During my visit, the primary path via the old bridge, which gives access to the heart of the Gearagh complex, was flooded out. In order to get across, walking in barefeet was the order of the day. I was fortunate on that occasion to be shown part of the site by Ted Cook, a resident of Kilbarry Hill, a tour guide with the Heritage Council and clearly an avid and passionate fan of this environment. Ted explains that The Gearagh can also be a very dangerous place to those not familiar with it. It is very easy to get lost. There are deep areas, muddy banks and floods do occur regularly.

The Gearagh occupies a wide, flat valley of the River Lee on a bed of limestone overlain with sand and gravel. The adjacent valley walls are of Old Red Sandstone. This unusual area has formed where the River Lee breaks into a complex network of channels (two to six metre wide) meander through a series of wooded islands. The alluvial (riverine) woodland is wet, marshy and overgrown, an environment, which creates ideal ecosystems (systems that change in nature every week). Here also, one can explore the effects of biodiversity change and the created haven for flora and fauna. In truth, the Gearagh has many landscapes from macro level to micro level (Dept. of Marine and Natural Resources, 2006).

The area has probably been wooded throughout the Post-glacial era i.e. since the end of the last Ice Age, which ended around 10,000 years ago. Frequent flooding has continues to enhance its character. Originally, this area of alluvial woodland extended as far as the Lee Bridge. Unfortunately, in 1955/56, in the eastern part of the Gearagh, extensive tree-felling and flooding were carried out to facilitate the operation of a hydro-electric scheme. Approximately sixty percent of the former woodland was lost (Dept. of Marine and Natural Resources, 2006).

View Kieran’s Exploring The Gearagh:

The Gearagh’s soil structure consists of ‘dry alluvium’ and supports an almost closed canopy of Oak, Ash and Birch. The ‘understorey’ is of Hazel, Holly and Hawthorn. Willows and Alder are largely limited to channel margins and waterlogged areas. The ground flora reflects the damp nature of the woodland. In spring, Ramsons and Wood Anemone are widespread. Later in the year, other species appear, including Bugle, Pignut, Irish Spurge, Tufted Hairgrass, Enchanter’s Nightshade and Meadowsweet. Plants species of particular interest within the woodland are Wood Club-rush, Bird Cherry and Buckthorn. These species are scarce in Ireland. Lichen communities are well developed in the lower levels (Bryophyte levels) of the woodland.

Variations in the flora occur locally, where drainage is hindered and where tree clearance has occurred. In truth, the entire area has a remarkably wild character, with many fallen trees blocking the channels, so that access both by foot and boat is difficult (Dept. of Marine and Natural Resources, 2006).

Within the reservoir, the former extent of the woodland can still be seen at times of low water. The cut stumps of larger trees remain prominently preserved in place. At least five species of Pondweed occur in the reservoir, including two species, which are uncommon in Ireland. At low water levels, a diverse ‘ephemeral’ flora develops on the exposed mud. Species here include Water Purslane, Knotgrasses, Trifid Bur-marigold, Marsh Yellow-cress and Six-stamened Waterwort (Dept. of Marine and Natural Resources, 2006).

In The Gearagh, the river channels have also created marginal alluvial grassland in places. Wildfowl graze these grasslands, as well as some semi-improved grasslands within the site. Extensive pastures of Mudwort, a rare plant, occur on the mudflats along the reservoir. Otters are frequent throughout the site. The Gearagh supports part of an important wintering bird population: the area most utilised by birds extends also east of the site, towards Cork city (Carrigadrohid). At The Gearagh, Whooper Swans are regular as are Wigeon, Teal, and Tufted Duck. Golden Plover utilise the site on occasions, while there is a regular flock of Dunlin, a species unusual at inland sites. A late summering flock of Mute Swan is regular. Great Crested Grebe and Tufted Duck breed in small numbers, while there is a undomesticated flock of Greylag Geese (Dept. of Marine and Natural Resources, 2006).

Little felling has occurred since the early 1950’s and the installation of the Hydro-Electric Scheme. The least disturbed part of woodland occurs in the upper reaches of The Gearagh. Tree regeneration is occurring around the reservoir, which may restore some of the lost portion of woodland (Dept. of Marine and Natural Resources, 2006). The Gearagh has been a nature reserve for twenty years and under the direction of the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the ESB (who own the site).

Further Footprints of a Saint- St. Finbarre’s Church, Macloneigh:

In the eastern section of The Gearagh or in the northern section of the basin created for the River Lee by the hydro-electric scheme, the river travels around the tip of a small type of peninsula. The Lee Bridge, built in the 1950s, spans from the R584, the regional road to Uíbh Laoghaire into the Parish of Macloneigh. The local townland names adjacent the Gearagh and Carrigadrohid Reservoir include Toombog, Coolcour, Farranavarrigane and Inchinashingane. Toombog or Currach na d’Tuamacha means ‘Bog of the Burial Mounds’, Coolcour or Cúil Cobhair means ‘Recess of Froth’ from the joining of the Rivers Lee and Sullane, Farranavarrigane or Fearann Aimheirgin meaning ‘Amergin’s Holding’ and Inchinashingane or Inse na Seangan can be translated as ‘River Inch of the Ants’.

Traveling over the Lee Bridge towards Tooms, there is a trackway immediately on your left, which leads to the site of another ancient church named after St. Finbarre. Here is another link to the fabled walk of the saint. The ruins of the old church, of unknown construction date, are situated in the Cill Field or Pairc na Cille meaning ‘Field of the Church’. The area is also known as Tuaim Musraighe meaning Burial ground of Muskerry. The ruinous church is built atop a rock outcrop overlooking the River Lee and anyone passing through this area, centuries ago would have seen the imposing structure.

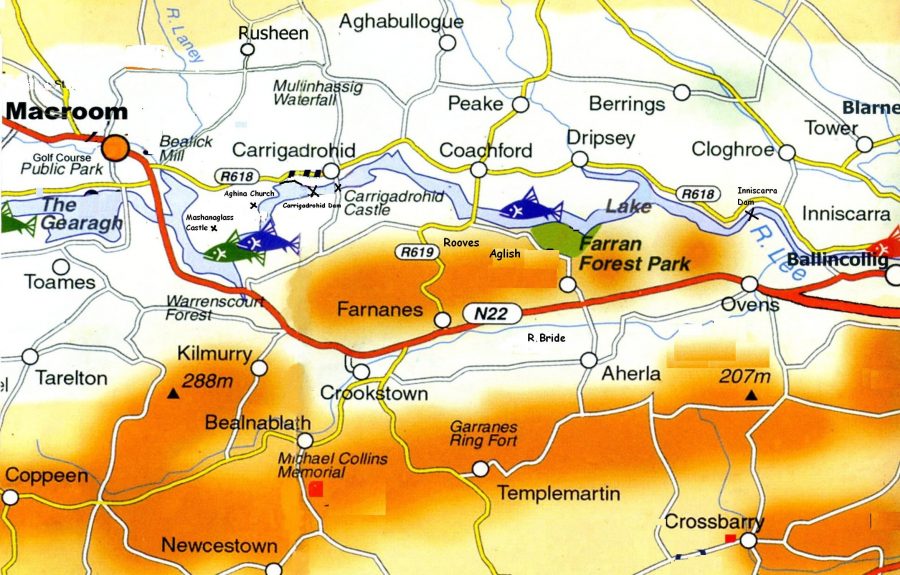

Macroom – The Frontier Town:

Macroom is said to have derived its name, from the Irish language ‘A Crooked Oak’, from a large oak tree formerly grew in the market square. As a settlement, it owes its origin to the erection of a castle, which was built in the reign of John by the Anglo-Norman family of the De Cogan (c.1200). This castle subsequently became the property of the McCarthys, and was repaired and improved by Teigue McCarty, who died there in 1565.

Upon the plantation of Munster, in the late 1500s, the McCarthys were the King’s local ‘steward’ and were also known as Lords of Muskerry. They were obliged to encourage the settlement of several English families of the Protestant religion into the Macroom area. The new names which took up resident were the Hardings, Fields, Terrys, Goulds and Kents. The colonisation led very quickly to large-scale Anglicisation, which was an attempt to destabilise Irish society by introducing new English ways of laws and social traditions.

In May 1703, the Hollow Sword Blade Company purchased the Castle and lands and from them the legal rights were passed on over succeeding years. Macroom Castle was burnt out on the 18th August 1922 following the evacuation of the British Auxiliaries, who had commanded it as a residence in 1920. About 1924, Sam Williams, a prominent local Church of Ireland man and a Roman Catholic Macroom merchant Jeremiah O’Leary approached resident Lady Olive Ardilum to secure the Castle’s demesne as a recreational area for the people or Macroom. She sold the castle to the new local trustee-committee for a reasonable price but reserved the site of the Castle. The trusteeship still exists today.

In early 1967, the main building of the Castle, under the auspices of the Office of Public Works, was demolished due to concerns over safety of the building. In the early 1970s, McEgan Secondary School / College was constructed on the site of the Castle. The 97 acres of demesne is now is now open to the general public and boasts a new nature trail, which encompasses the old nineteenth century beech avenues that led up to the main house. Macroom Golf Course also provides a recreational area with views of the River Sullane.

The Aghinagh Way:

The R618 provides fine views of Carrigadrohid reservoir and also introduces the explorer to the heart of the Parish of Aghinagh and the Aghinagh Way, a heritage trail, which was produced by Aghinagh Heritage Group in 1999. The Way introduces a treasure trove of archaeological sites such as ringforts, standing stones, wedge tombs and famine sites in areas such as Musheramore, the River Laney Valley and Ballinagree. Three different degrees of cycle tours mainly through the parish of Aghinagh with the town of Macroom as a base. Aghinagh parish is ten miles long encompassing Mushera Mountain and the old Butter Road to the north and the River Lee and villages such as Carrigadrohid to the south.

There are many possible explanations of the name Aghinagh such as Aghina belonged to Aghina, a grandson of Laoghaire. Another explanation is Ath Theinne or ‘Ford of Fire’ or the ‘Ivy-covered Field’. Within the parish is Ard Eidhinn Cross, which means ‘Heights of Ivy’. Other townlands, which adjoin the western bank of the reservoir consist of Ummera or Iomaire meaning ‘Ridge of Hill’, Rosnascalp or Ros na Scailp meaning ‘Shrubbery of the Clefts or Shelters’, Coolacoosane, Cúl a’Chuasain meaning ‘Hill Back’ or ‘Corner of the Cavern’, Coolacareen or Cúl a’Chairthin meaning ‘Recess of Hill-back of the Little Pillar Stone’ and Caum or Cam meaning ‘Bend’. In fact, after a small journey northwards, the River Lee turns eastwards again flowing towards Carrigadrohid Village.

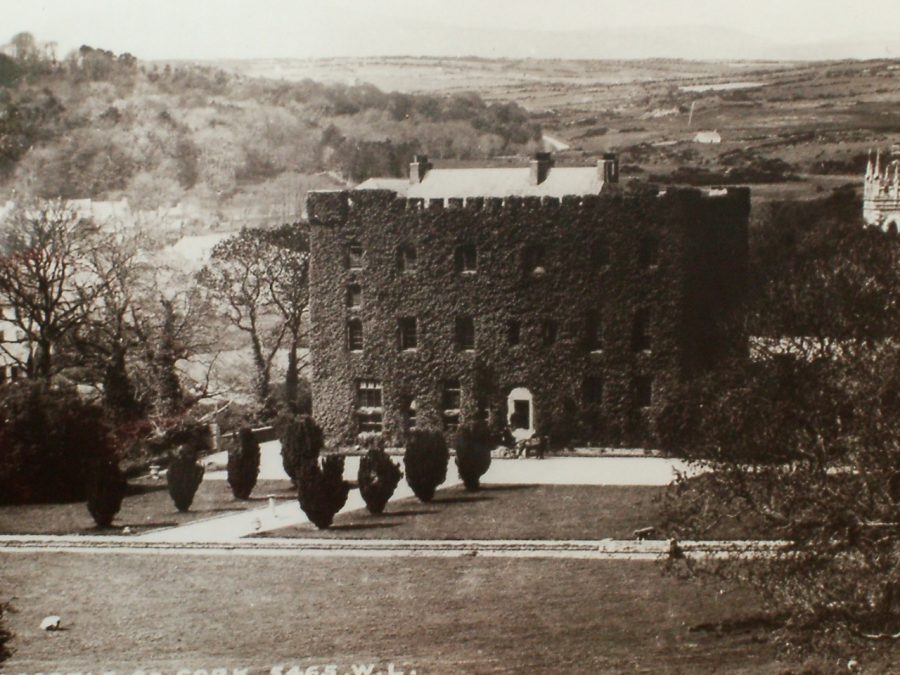

Mashanaglass Castle:

Mashanaglass Castle is a key monument of antiquity in the Parish. Magh Sean Glas means ‘The Old Green Plain’. The current ivy-covered ruin was a structure built by the McCarthys and lies between Coachford and Macroom overlooking Carrigadrohid Reservoir. From map evidence indicating the former presence of a moated site, the Normans may have settled here during their initial years of invasion (c.1169 onwards). However, it is written that in the year 1584 that the existing castle was occupied by the family of the MacSwineys, a professional Irish army in the employment of the McCarthys.

In 1865, it is reputed that a person searching for treasure or stones from the building placed a charge of gunpowder under the south-east corner. The resultant explosion did not bring him profit but caused extensive damage to the building.

As part of the preparation work for the Hydro-Electric Scheme, Archaeologist, Edward M.Fahy excavated a Horizontal Mill at Mashanaglass in 1955. It was originally believed to have been a well and was known locally as Tobar an Ratha. Prior to the excavation the site consisted of a three-walled dry stone structure of rectangular plan sides. Religious objects and personal mementoes had been affixed to the tree alongside it. During the excavation large numbers of white pebbles were found in the sods surrounding the well. These were recorded as “Hail Mary” stones, as it had been customary for pilgrims to drop them in the well or leave them on the site as part of the “rounds” at the holy well.

The water from the well was also said to cure sick babies. One of the old customs was to immerse the infants in the water. If the child turned pale or a pink colour it would die but if it turned red it would live. The excavation work however revealed that the well was in fact one of the most unique mills of its kind in Ireland. The date of its construction is unknown but the mill was in use up to the 1700s. A model of the mill is on display in the museum in Fitzgerald’s Park in Cork city. The Mill has been destroyed but its remains as well as the Holy well can be viewed in Mashanaglass area.

Carrigadrohid Castle:

Castles like that Carrigadrohid were the fortified residences of local lords and chieftains, both of the native Irish families and the descendants of the Anglo-Norman settlers. It is said Cormac McCarthy built the castle in the year 1445 to please Sabina O’Carroll, who was his bride to be. Castles were frequently built close to river crossings in order to control movement along and across river valleys. The particular example at Carrigadrohid is rare due to the fact that it was built in the river, on a rocky island. The presence of a rock outcrop in the river made the site a natural bridging point. Relatively simple wooden structures were sufficient to span the two channels formed by the rock outcrop. However, it is really at low water level when you get to appreciate the immense engineering that went into building a castle on the bedrock. The same rock has been eroded away by the river but also through the forces of glaciation, thousands of years ago.

A modern stone plaque on the walls commemorates the hanging of Bishop MacEgan in 1650. In 1703, the Hollow Sword Blade Company gained possession of the Castle. In 1724, John Bowen, an ex English soldier, married Elizabeth Chidley Coote and moved from Kilbihane to settle at Carrigadrohid.

In the early 1800s, the Bowens abandoned the Castle to live in their nearby new residence called Oakgrove House.

The Castle has been derelict for many years with falling masonry a common feature in its present existence. There are contemporary efforts to preserve the structure. It is sad to think of its impending collapse. It is such an imposing structure proudly standing and promoting not only its past but the identity of the people living in the present area. Despite the fact that we cannot talk to its former residents, it is clear that so much human effort and emotion was put into its construction and maintenance.

View Kieran’s Exploring Carrigadrohid Castle, Co. Cork:

Coachford – The Crossing of the Coach:

From Carrigadrohid the River winds its way east and finds itself in Inniscarra Reservoir, large body of water just over fifteen kilometres long and on average 300 metres wide. The townlands along the northern side of Inniscarra Reservoir comprise Coolnagearagh or Cúl an Gaorthaidh, which means ‘Hill-back of the Wooded Glen’and Carhoo or Ceathramha means ‘Quarter’.

Coachford or Ath an Choiste can be translated as the ‘Crossing of the Coach’. This was where the Cork-Tralee Mail Coach crossed the River Lee. A relic of this important function is enshrined in the nearby Rooves Bridge, which was built in the early 1950s as part of the Lee Hydro-Electric Scheme. The previous structure nineteenth century in date had nine semi-circular arches and had a similar appearance to Inniscarra Bridge.

The Place of Dripsey:

Following the R618 along from Coachford, the townland names adjacent the northern bank of Inniscarra Reservoir from Roove’s Bridge to Inniscarra echo the human connection to landscape. Fergus or Feargus highlights the ‘Home of Fergus’ who lived about 600 A.D. Feargus was the grandson of Tighernach and became a holy man and lived with St.Finbarr at his monastery at Corcach Mor na Mumhan or the ‘Great Marsh of Munster’ (now the City of Cork). Cronody or Corra Noide means ‘Stone Enclosure of the Church’.

Dripsey or An Dripseach can be translated as ‘Muddy River’. It is here that the Dripsey River joins the River Lee. Dripsey Bridge is of nineteenth century design and part of it was blown up the Irish War of independence in 1920. Just approaching Dripsey from the Coachford side is the Ambush Cross Roads. Here an obelisk with a sculptured sword is erected to the memory of the sixth battalion. This was the first Cork brigade of Irish Republican Army captured whilst engaging British forces on the 28 January 1921. They were subsequently executed in Cork Prison on the 28 Febraury 1921. Captain Jim Barrett died in the Cork Prison on the 22nd March 1921. His comrades Timothy McCarthy, Padraig O’Mahony, Sean Lyons, Donal O’Callaghan and Thomas O’Brien are also remembered.

The nearby tiny village of Dripsey, once boasted a paper mill, a cheese factory and one of the last original working woollen mills in Ireland. High above on the picturesquely-named Carrignamuck or Rock of the Pig, fifteenth-century Dripsey Castle stands guard remembering more violent times as it watches the peaceful village. On one day in the year, little Dripsey bursts into a view of colour, crowds and music. Flags and bunting are hung from every rooftop and telegraph pole, the local Garda sergeant is directing traffic, and hundreds of onlookers line the road. Because this is St. Patrick’s Day and for the past seven years Dripsey has been staging what it proudly claims is the shortest St. Patrick’s Day parade in the world from the Lee Valley pub to The Weigh Inn pub.

Inniscarra –Island of Friendship:

Inniscarra has a strong association with the River Lee valley and is well known by Corkonians. The area is noted for its scenery with its reservoir lake, lush green fields as well the modern industrial symbols of Inniscarra Hydro-Electric Dam and the waterworks. Prior to the construction of the ESB Dam, flooding downstream was an annual feature due to the topography and climate of the Cork region.

In recent decades, the Dam has acted in curbing the river as the principal reason for flooding. The ESB issues flood warnings to those known to be at risk downstream of the dam during periods of floods. The concrete dam at Inniscarra is of the buttress type, is 250 metres long, 42 metres high and has three spillway gates. The immediate head race has a depth of thirty metres of water which provides pressure and energy. In the complex, there are two vertical shifts Kaplan turbo generating with an output capacity of fifteen megawatts and four megawatts respectively which produced. Hence Inniscarra can produce over 55 million units of electricity a year. Power is generated at 10.5 kilovolts and transformed up to 38 kilovolts for local distribution and up to 110 kilovolts for long distance transmission.

When Hugh O’Neill and his men rested in the area on their way to Battle of Kinsale in 1601, O’Neill thanked the monks he stayed with for their friendship and for their hospitality and named the place Inis Cara or Island of Friendship. The monk’s settlement was Inishleena or Inis Luinge, which means the ‘Island of Encampment’. Legend has it that St. Senan set up camp about 530 A.D. and built an abbey before going downstream to Inniscarra.

The abbey was demolished in the 1700s and the stones were used to build local houses. There is no visible trace of the old building but a new church was constructed nearby in the early 1700s. Over the western door of the tower is an inscribed plaque commemorating its erection in 1756. The adjacent graveyard is enclosed by a stone wall and is still in use. A large collection of eighteenth century and nineteenth century headstones exists to the south of the church ruins. The earliest noted date is 1770. Just north of the ruined church are five gabled mausoleums. In the most easterly section lys the largest with near identical pedimented gables. All five have suffered from vandalism.

Canovee to Carrigdrohid – A Pride of Place:

The N22 from Macroom to Cork offers the pilgrim a view from the southern bank of the River Lee / Carrigadrohid Reservoir. In the middle of the reservoir one can see extant sections of two bridges from the Cork-Macroom railway line. One can be seen quite clearly in the middle of the Reservoir whilst the other section can be viewed from Bealahaglashin Bridge and is on the grounds of Con O’Leary’s scrapyard. The River extends from the Reservoir in a north-easterly manner.

To follow the river, the traveller must leave the N.22 and travel north on third class roads, which are signposted as the N.22 leaves the Reservoir district on its route to Cork. This area is Canovee Parish or in the history books is noted as Cannaway Parish. Ceann A’Mhuighe means ‘Head of the Plain’ or it can also mean Ceanna Bhuidhe meaning ‘Yellow Peaks’ or ‘Sunny Peaks’. At this point, the Buingea River joins the River Lee. The townlands adjacent to the Lee on the southern bank all the way to Carrigdrohid Dam comprise Lehenagh, Coolnacarriga, Monallig, Bawnatemple and Killnardrish.

Lehenagh or Leitheanach means ‘Broad Plain Over the Glen or River’. At the southern end is Aghthying Bridge or Ath Domhain meaning ‘Deep Ford or Crossing’ and Bealasheen Bridge or Beal Aithin meaning ‘Passage of the Little Ford’. The Aghthying River flows through the townland to join the Lee. Coolnacarriga or Cúl na Carrige means ‘Hill-back of the Rock’. Classes or Clasa means ‘Hollows’ or ‘Valleys’. Monallig or Moin Ailigh means ‘Rock’ or ‘Boulder’. In recent centuries, slate quarries were worked on the northern side of the townland. Bawnatemple or Badhún An Teampaill means ‘Enclosure of the Church’.

An ancient church was erected in the area and was reputed to one of the largest early monastic enclosures in Munster. In 1817, a Protestant Church opened near the older church and this is also a ruin amidst a surrounding graveyard. Killinardrish or Cill an Ard Dorais can be translated as ‘Church of the High Door’. In the Civil Survey of Muskerry in 1640, it was noted that another parochial church was located in this townland near the bank of the River Lee.

Carrigadrohid to Rooves Mor:

Leaving Carrigadrohid and following along the southern bank towards Rooves Bridge and Coachford, one cannot but admire the pillars of Nettleville Estate once the home of R.Neville Nettles. Samuel Lewis in 1837 notes that the other principal gentry houses in Canovee Parish were Killinardrish House, the residence of R. Crooke, Llandangan House that of S. Penrose, Lieutenant Col. White’s Rockbridge Cottage, T.Gollock’s Forest House of, J. Bowen’s Oakgrove, W.Furlong’s Coolalta and an elegant Italian styled lodge, which was the home of R.J.O’Donoghue.

There is another memory as well in this region that remembers the poorer classes. Moving further east on the road,Soup Kitchen Cross Roads is encountered. Here a memorial was erected in 1998 by Canovee Historical Society to recall Ireland’s Great Famine and the efforts made to provide relief to those residents in Canovee Parish. Travelling east, the road travels alongside the Kame River as it enters Inniscarra Reservoir. Rooves Bridge provides access across the Reservoir to Coachford. Rooves Mór and Rooves Beg are two large townlands. Rooves or Ruaidhtibh can be translated as ‘Reddish Spots of Land’.

Here is Our Lady’s Well. The rounds involving walking around the well house clockwise and comprise seven sets of seven Our Fathers, seven Hail Marys and seven Glory be’s. After the seven sets, one drinks the water from the well and blesses oneself. One then makes seven crosses on the side of the well and ties a piece of cloth on a whitethorn tree. Whatever ailment one has is supposed to blow away with the cloth on the tree. No one touches the cloth for fear of getting the ailment. The rounds are completed over three days on a Sunday, then the following Friday and Sunday. Extra powers were granted on Palm Sunday, Good Friday and Easter Sunday.In particular,the well is said to cure toothaches and headaches.

One of the legends attached to the well is that St. Olan from Aghabullogue gave tuition to St. Finbarre at the well as he walked down the River Lee. Another legend is that the water of the well does not boil.

Farran Woods:

The forest, which is 44 hectares in extent, once formed a mere fragment of the vast Farran estate which was owned by a Captain Clarke – of tobacco products fame. The demesne passed on to Captain Mathews who converted some of the pasture land to forest. Being a keen sportsman, the Captain, as well as planting conifers and broadleaves planted some carefully sited clumps of broom, laurel and rhododendron to provide cover for game birds. These are still to be found in Farran wood, which is now managed by An Coillte.

Farran Woods contains a large duck pond and wildlife enclosure. Originally a “flighting” pond” it was greatly extended in the 70’s and a number of species of duck and geese were added. The collection includes Mallard, Teal, Widgeon, and Shoveler duck along with Greylag, White Fronted, Barnacle, Snow and Egyptian geese. Red and Fallow deer are to be found in the enclosure which is surrounded by a gravel path thus providing clear views of the wildlife. An old shooting lodge adjacent to the wildlife enclosure has been converted into a woodland ecology display centre.

Farran Woods is also the home of the National Rowing Centre. The first rowing regatta was held on Inniscarra Reservoir in 1975. At that time, still- and lake-water coursing were becoming popular. In 1974, Shandon Boat and Rowing Club wished to mark its centenary the following year with something different from the norm. Mick O’Callaghan was Captain of the Club at the time. The organizing committee were members who Mick had rowed with as a youth, John Cashell and Andy O’Connor. The senior member was Mick Collins, Vice-President of Shandon Boat Club. They laid out six lanes, two-thousand metres from Farran to the rowing centre at Rooves Bridge. Mick O’Callaghan recalls:

“We made a timber starting platform. The lanes were made of 12,000 metres of bailing twine and 700 / 800 one-gallon plastic containers, painted orange. Boats started from a platform made out of pallets, rope and concrete. The ESB were very helpful as were the local farmers at Rooves bridge. Mr McSwiney, the local farmer, gave us a section of his land for the day. We made slipways out of pallets”.

In July 1976, the Home International Regatta was held over one day on Inniscarra lake. It was an international rowing competition between Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales. On the second day, Shandon Boat Club held their annual regatta. During the 1980s and 1990s, regattas were held intermittently on the reservoir.

There was no set plan – the Irish Championship was held on the reservoir, while club regattas took place over the former site of Inisleena abbey. The Cork Regatta was held there once or twice. The Dripsey channel held the Intervarsity College Rowing Championships, and UCC Rowing Club trained here also. In the early 1990s, the move to using multi-lane courses intensified – Cork City Regatta recognized the need for development and moved out to the reservoir in 1992. In 1997, the Irish Championship was held on the reservoir where it has taken place ever since. The European Junior Championships took place at Farran in 1999. In the late 1990s, Cospóir, the sport-development body in Ireland, wanted to upgrade international facilities and approached the National Rowing Union. Cork City Regatta Committee proposed the Farran venue, and a stretch of water was nominated on Inniscarra reservoir and recommended by an international expert. It was deemed as the best place to build the National Rowing Centre in the country.

View Kieran’s “Exploring Farran Woods”:

Aglish:

Very few regions in County Cork have a holy well in good condition but in the adjacent Aglish Parish, there is another well-kept well dedicated to Our Lady. Seven kilometres to the east of Rooves in the townland of Walshestown. There are the remains of three Medieval churches within four miles of Aglish. Near Aglish Cross Roads are the remains of two ancient churches in ruins. They are built at right angles to each other and overlook Farren Woods. The older in a north-south alignment and the younger in a west-east in direction. The older building is the same size of Macloneigh church – nearly twenty-five metres in length and ten metres in width. The gable walls are all over grown and large section have been reduced to just a mound. Within the interior of the older church is a tomb with a date of 1795. Both churches just have name Aglish. In the associated graveyard, there is a section for famine victims with stone stumps protruding from the ground.

The third church is St. Finbarre’s Church and this is located three kilometres to the east near the reservoir bank in the townland of Ballineadaig or Baile an Eadaigh meaning ‘Eady’s Habitation’. It might also read Baile an Eadaigh meaning ‘Place of the Cloth or Clothing’. The Church is called Cill na Cluaine meaning ‘Church of the Meadow’. This was one of the reputed places where St. Finbarre is said to have died in the year 623 A.D. Cloyne in East Cork is also a reputed place of his death. The Cill na Cluaine complex has all the hallmarks of being a monastic enclosure. Today, a low circular mound of earth encloses the low rectangular mound of a church. In the adjacent lands is a farmhouse, which is early 1800s in date and was once the hunting lodge of the Parker family. Today, it is the residence of the fifth generation of the Lehane Family.

Ballincollig- A Sense of Place:

In recent years, Ballincollig as a settlement on the southern valleyside of the River Lee has grown in size in terms of population and housing stock. The ‘village’ has expanded in accordance of the needs of its resident and commuter population. As an area of settlement, the functions of Ballincollig have changed over time. Those functions have ranged from providing defence in the shape of Ballincollig Castle in the Anglo-Norman Irish frontier in the 14th century through to providing houses and shops in the age of the nineteenth century Gunpowder Mills through to the creation and development in recent decades of a satellite town serving a population of over 20,000 people.

Archaeological excavations on the Ballincollig Bypass in 2002 / 2003 uncovered habitations sites (houses and Fulacht Fia) from prehistory and the evidence for Ballincollig’s first settlers from 5,000 years ago. From Neolithic contexts, a house was excavated during Bypass construction at Ballinaspig More (c.3,900-c.3,600 B.C.) as well as nearby ritual pit at Carrigrohane in which was discovered pottery, beaker pottery, flint fragments, charcoal and charred seed. From the late Neolithic and Bronze Age contexts, fifteen fulacht fia were excavated (c.2,500 B.C. in date). A Bronze Age to Late Bronze Age House (c.1,500 B.C.) excavated during Bypass construction at Ballinaspig More, Cremation pits were found at Barnagore (2,100 B.C.) and at Carrigrohane (c.1,500 B.C.). An Iron Age house was also excavated during Bypass construction at Ballinaspig More (340 B.C.). From Early Medieval contexts,two conjoined enclosures were excavated during Bypass construction at Curaheen. A house foundation was discovered plus an enclosure as well as associated finds (dating to c.700 A.D.).

Nearby is Ballincollig Castle, which was built in the early 1300s (A.D.) and was the castle of the Colls, an Anglo-Norman family (Robert). Hence the name Ballincollig or Baile an Chollaigh. The Castle was handed over to the Barrett family, a Norman clan in the barony of East Muskerry and after whom the barony, which contains Ballincollig is named). The Barretts had allegiances with local Irish families. The Castle was destroyed during 1641 and in 1689 it was garrisoned by troops of the Catholic King James II. In 1659, the manor of Ballincollig Castle was noted as eighteen inhabitants. The Castle was a ruinous structure until some renovations by the local landlord, Thomas Wise in the nineteenth century. Since then, the Castle has fell into decay.

Ballincollig Gunpowder Mills:

Ballincollig remained a small community till 1794 when Charles Henry Leslie, a leading Cork merchant established the local gunpowder mills, a unique industrial complex in southern Ireland. Shortly after, Oriel House was built by Leslie as his residence. Increased concern about the security of the gunpowder mills, coupled with the British government of the day’s policy for creating its own monopoly of gunpowder manufacture in these islands, greatly influenced the Board of Ordnance’s decision to buy out Leslie in 1805.

In March 1805 the Board appointed its chief clerk of works for powder mills, Charles Wilkes, as superintendent of the Ballincollig gunpowder mills. Wilkes began by improving access to the complex from the old Killarney road to the north, by entirely rebuilding Inniscarra Bridge replacing the six arched (original date of construction unknown) with twelve semi circular arches. The area of the barracks and mills, including administration buildings, a network of canals and the new cavalry barracks, was greatly expanded in the period 1806-15, and the greater part of the 431 acres involved was enclosed behind a high stone wall.

In 1810, the Army Barracks were built in town to protect the supply of gunpowder. The outer perimeter stone walls extended from the eastern gate of the mills to Inniscarra Bridge. Ballincollig Barracks was located to the northern side of the Main Street in Ballincollig town centre. In 1837, the army barracks contained accommodation for eighteen officers and 242 non-commissioned officers and privates. In the centre of the quadrangle, there were eight gun sheds and near them were the stables and offices. Within the walls was a large and commodious school room. The police depot for the province of Munster was situated here and the men were drilled till they become efficient and were then drafted off to the different stations in the province.

In 1834, the Board of Ordnance sold the Gunpowder Mills to the Tobins, a Liverpool family. About the year 1860, circa 500 people were employed in the gunpowder mills. Two of the raw materials for the gunpowder were imported from Sicily (sulphur) and India (saltpetre) and the third, charcoal was produced locally. The River Lee provided the power to turn the waterwheels for grinding the raw materials and manufacturing the gunpowder. Most of the finished product was exported to Liverpool before it was sent onto to Africa.

in 1888, the mills were bought by John Briscoe and soon came under the control of Curtis’s and Harvey. The mills closed in 1903 due to the advent of the production of dynamite. The Curtis and Harvey’s mills were then absorbed into Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). The site was bought by Cork County Council in 1974, who developed it into a public park.

Carrigrohane – A Geography Inspired:

From Ballincollig, the River Lee now meanders towards its meeting with the tidal water. Its journey is nearly over. On one side of the valley is Curraghkippane and on the other soaring above the scene just before one encounters the Carrigrohane Straight Road is Carrigrohane Castle. Carrigrohane translated means Carraig Raitheach or The Rock of the Ferns. The second translation is Carraig Rothain or The Rock of the (Hangmans’s) Noose.

The development of Carrigrohane Castle from its origins to the present day has been inspired by its geographic location, especially located so close to a cliff face and the fact it overlooks the River Lee and overlooks one of the principal approach roads leading into Cork. In fact, its walls overlook Hell Hole – a favourite swimming and fishing haunt for many centuries near the present day Angler’s Rest Pub.

The development of the site began about the year 1180, when King Henry II granted Milo De Cogan, an Anglo-Norman lord, several hundred acres lands south and west of the walled town of Cork. In 1207, Richard DeCogan, a relative was given the manor of Carrigrohane and his successors built a castle. In 1464, on the occasion of a new charter granted to the City of Cork, the western limits of the liberties of the city were Carrrigrohane Castle. In 1317, William Barrett, in consequence of his father Robert working with the King’s armies against the “King’s enemies” was granted two parts of the local land of ‘’Gronagh’ and the castle (Healy, 1981).

By the 1400s, the DeCogans of Carrigaline returned as overlords of the Barrett property. In the 1500s, the castle supported the Irish Earl of Desmond in his revolt against the English crown. When the Earl of Desmond’s uprising failed, the Queen’s Lord Deputy c.1600 gave a lease of Carrigrohane to Sir Richard Grenville with a provision that he would repair the ruined walls of the castle and to build a new house. Subsequently, the lands were given to the custody of Sir William St. Leger. The new house could be described as a Tudor Castle – a type of semi-fortified mansion with three storeys lit by four windows on each storey. The medieval castle has partly survived next to the present day dwelling.

Near Carrigrohane Castle is the imposing limestone structure of St. Peter’s Church, which was originally built in the seventeenth century as a Protestant Church. Samuel Lewis in 1837 described it as a ” small plain edifice” which had been repaired in the 1830s. Several changes were witnessed in the ensuing decades.

Lee Fields – Journey’s End:

The Lee Fields extend from the County Hall for just over two and half miles. The weir provides a boundary of the River’s fresh water and tidal water. It is here that during all months that the die-hards swim in the Lee, where people walk their dogs, where fitness fanatics jog and stretch to couples discussing the day’s challenges or those who watch the waters flow. It is here that the River Lee splits into two creating a north and south channel, both channels encompass the city centre islands. One can see the northern channel as struggles to carve an initial path for itself whilst the south channel flow on with ease. St.Finbarre’s Cathedral overlooks the southern channel and stands to recall journey’s end and a beginning for Cork’s Patron Saint.

WALK ON & EXPLORE the Lee Fields: History Trail, Lee Fields | Cork Heritage