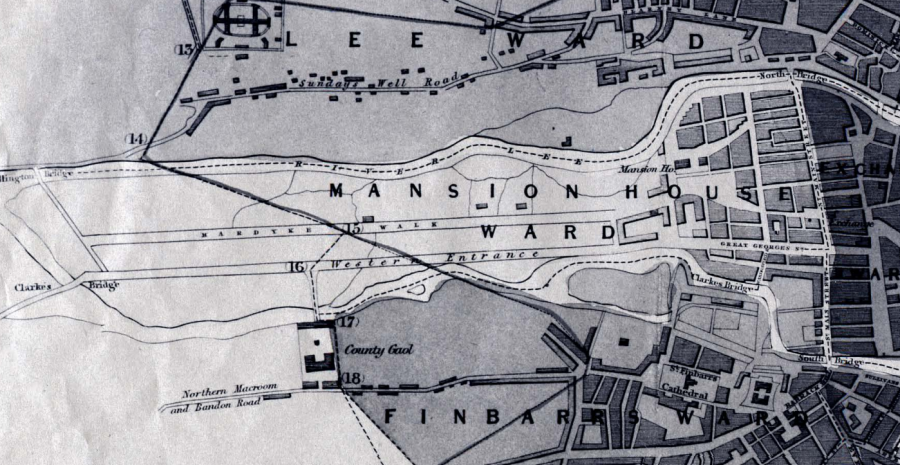

See a close-up of Beauford’s map of Cork here: 1801_beauford_colour.pdf (corkpastandpresent.ie)

Napoleonic Wars:

The advent of the nineteenth century brought a change in political circumstances for Ireland and for Cork. The fear of further rebellions against British rule led to the Act of Union in 1800. This was a seismic event in Irish history. The Act of Union abolished the separate Irish Parliament in Dublin, and from then until 1922 Ireland was governed directly from Westminster. Cork Corporation and the mercantile class supported the Union because it led to increased trade with Britain. This unpopular stance made the city vulnerable to attack, so a new barracks was constructed in 1806. It is still a military barracks, but is now called Collins Barracks, after Michael Collins.

Britain also benefited from the Act of Union. The early nineteenth century was a turbulent time in northwest Europe, with conflict between Britain and France. This resulted in reduced imports from the European mainland to Britain, leaving Britain with an urgent need to find new trading partners. Cork was to fulfil this need.

In The Stranger in Ireland (1805), John Carr, a gentleman traveller and writer, described the city’s export fever. Cork possessed the largest shambles, or slaughtering houses, in Ireland. The slaughtering season started in September and continued to the end of January. Carr recorded that 100,000 black cattle were killed and cured each year in Cork, largely for export to Britain.

Gunpowder Provision:

Britain not only traded in food produce, it also imported munitions from Ireland. Charles Henry Leslie, a banker, and John Travers, an industrialist, established the Ballincollig Royal Gunpowder Mills, eight kilometres east of Cork, in 1794 and set up a manufactory over an area of ninety acres.

By 1805, the English Board of Ordnance had become involved in their venture and the mills were the most important military-industrial complex in Ireland and Britain, employing several hundred people and providing gunpowder for all major British offences across Europe. The provision of housing for workers created the basis for a village at Ballincollig. The ruins of the mills and workers’ houses can still be seen and a local heritage centre tells the story of the Royal Gunpowder Mills.

Economic Recession:

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 exposed many of the hidden dilemmas within Cork’s economy. In the immediate post-war era, a general recession ensued and there was no substantial demand for Irish products. Where a demand did exist, export profits were low as prices fell. For example, between 1818 and 1822 grain prices were halved, while the price of beef and pork fell by about one-third. Cork also struggled to regain its international links. The scale of production changed from international to local in nature as the city tried to recreate previous trends by using the surrounding agricultural hinterland to bolster the local economy.

For the working classes, the cessation of the Napoleonic Wars meant large-scale unemployment, especially for those previously involved in the provision trade, from preparing meat for export to working on the export ships. The resultant fall in income meant food was scarce and housing conditions deteriorated. This in turn led to epidemics such as typhoid sweeping through the city.

In the Statistical Survey of County Cork (1815), Horatio Townsend highlighted the stark contrast between the middle and lower classes. He placed a particular emphasis on the need for de-concentration of people in the worst parts in the city, namely the slum areas of North and South Main Streets and around Barrack Street on the southside and Shandon Street on the northside.

The housing crisis was exacerbated by the influx of County Cork labourers into the city, who arrived in search of work and food. As a result, there was an extra 10,000 people residing in the city in 1821, bringing the population to approximately 100,000 without any concomitant increase in the housing capacity. Although we do not have an exact figure, it is likely that several thousand people emigrated from the city in the first two decades of the 1800s.

In the case of the middle classes, short-term economic pressure was offset by the fortunes made during the war years. In the city there was a new incentive to sell houses in the central areas of the town as there was a sudden British interest in land and industry in Cork, inflating property prices. More and more middle class people moved out to the suburbs, to Douglas, Mahon Peninsula and Montenotte.

See a close-up of Chalmer’s Map of Cork in 1832 here from Cork City Library: 1832_chalmers local survey_high_res_2011.pdf (corkpastandpresent.ie)

Funding for Projects:

In 1822, the British economy began to recover and funds were made available for Irish issues. The Wide Street Commission was re-instigated after an absence of nearly half a century. Their main aim in the early 1820s was to redevelop older areas for a new century. One of the main projects undertaken was the destruction of the large slum areas around South Main Street. Consequently, the boulevard-style Great Georges Street was opened in November 1824. The street cut through the old medieval core and onto the western marshes. It was renamed Washington Street after 1922.

Work on a new road, known as the Western Road, commenced in 1821 and it was completed by 1831. It joined Great Georges St and a new bridge named Brunswick Bridge (now O’Neil Crowley Bridge), which spanned the southern channel of the River Lee. The bridge, designed by brothers James and George Richard Pain, has three segmental arches. Other municipal initiatives involved the introduction of gas lighting into the city in June 1825 and the extension of the Western Road across part of the Mardyke to the north channel of the River Lee. Another arched stone bridge was built in 1826, designed by Richard Griffith and the Pain Brothers. It was known as Wellington Bridge, later renamed Thomas Davis Bridge.

With the availability of funding, another institution, the Cork Harbour Commissioners, established in 1813, was able to carry out essential work on the quaysides and harbour. A large majority of the parapet walls that guarded the quays were replaced with limestone pillars. In addition, a new city custom house was constructed in 1814. The building is still used by the Port of Cork Company, the latest name for the Harbour Commissioners.

Elegant Buildings and Streetscapes:

From the 1830s onwards, elaborate municipal buildings and elegant streetscapes were constructed. Influenced by a wider trend in Irish and British cities towards elaborate architecture, these new edifices were a celebration of the social, intellectual and technological changes that had occurred in the British Empire in the previous fifty years. Banks, a city courthouse, a new city gaol and a new county gaol were all built at this time, along with many Catholic churches thanks to the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829. The design of many of the public buildings was the work to two families, the Pains and Deanes. Rivalling each other in talent and ambition, they accepted contracts on behalf of public bodies and from private individuals.

Read more and Explore more: 5b. The Great Famine in Cork City | Cork Heritage