Trails Starts at Flying Enterprise Bar, Barrack Street:

Below is a brief historical walking trail, which covers some of the topics on my physical walking tour. The information is abstracted from various articles from my Our City, Our Town column in the Cork Independent, 1999-present day, Cork Independent Our City, Our Town Articles | Cork Heritage

Introduction:

The chosen sites in this Barrack Street guide are fascinating markers of the city’s development through the ages, and diverse architectural style represent each phase of Cork’s growth. This guide details a basic cross-section of the area but also aspires to tell an intriguing story that perhaps needs to retold, so that a new generation of Corkonians can enjoy, appreciate and be proud of the Barrack Street area.

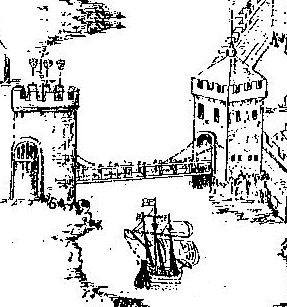

South Gate Bridge:

In the time of the Anglo Normans establishing a fortified walled settlement and a trading centre in Cork around 1200 A.D., South Gate Drawbridge formed one of the three entrances – North Gate Bridge and Watergate being the others. South Gate Drawbridge was a wooden structure and was annually subjected to severe winter flooding, being almost destroyed in each instance. A document for the year 1620 stated that the mayor, Sheriff and commonality of Cork, commissioned Alderman Dominic Roche to erect two new drawbridges in the city over the river where timber bridges existed at the South Gate Bridge and the other at North Gate. South Gate Bridge became known as Roche’s Bridge after its commissioner.

In May 1711, agreement was reached by the council of the City that North Gate Bridge would be rebuilt in stone in 1712 while in 1713, South Gate Bridge would be replaced with a stone arched structures. Both North and South Gate Drawbridgs were designed and built by a George Coltsman, a Cork City stone mason/ architect. South Gate Bridge still stands today in its past form as it did 280 years ago apart from a small bit of restructuring and strengthening in early 1994.

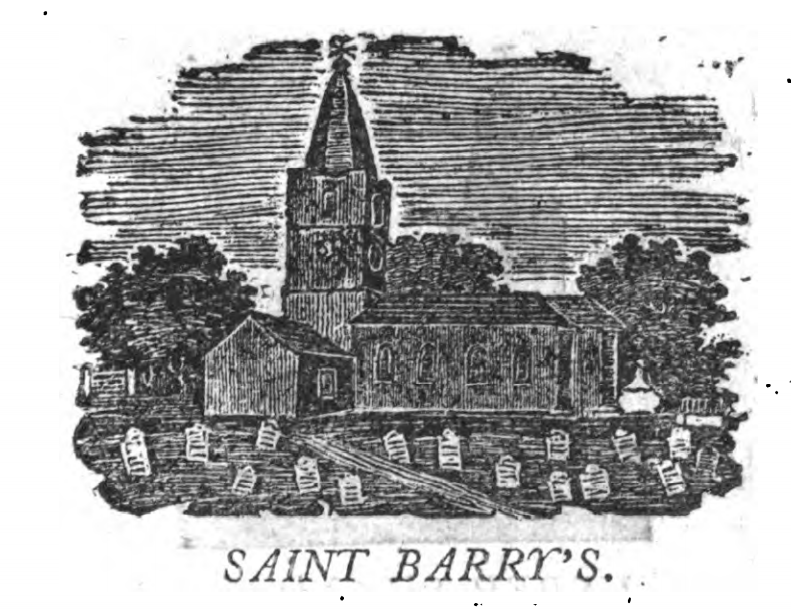

St. FinBarre’s Cathedral:

St. FinBarre’s Cathedral is a marker of the once vibrant early Christian monastery (c.600 A.D.) of St. FinBarre. During the 1860s in Cork, there was a strong increase in the re-appreciation of church architecture and it is clear that church buildings became an excellent and expressive means of promoting the influence of Protestant and Catholic communities within the city’s landscape.

Present day St. FinBarre’s Church of Ireland Cathedral echoes the resilience of the Protestant community. T

The date of the original foundation of St Finbarre’s Cathedral is not known with any degree of certainty but it was probably founded in the Early Christian period. It passed out of Roman Catholic hands about the year 1510 when Dominic Tirry, Rector of Shandon Church was appointed successor to John Fitzedmond Fitzgerald, who died in 1530.

The existing church received so much damage during the siege of Cork in 1690 that it had to be taken down, with the exception of the steeple, in 1725, and a new structure was built in 1735.

The 1735 church was a plain classical building, which retained the original tower of the first church. It was taken down in 1865 to make way for, in the words of the bishop of Cork, Gregg at the time, ” a structure more worthy of the name, Cork Cathedral”.

A general committee was formed to address the question of funding for a new building and to choose it architectural design. In 1863, a competition was arranged to find a suitable architect. The unanimous choice out 68 entrants from Ireland, Britain and the continent was for the design inscribed “Non Mortuus Sed Virescrit”, which means “He is not dead but flourishing”. William Burges was not just an architect but a person with numerous talents. Born in London on 2 December 1827, he was the son of a successful civil engineer and educated at King’s College London.

The general shape of the interior consists of a central nave or aisle with two side aisles, which run in a semi – circle to form an ambulatory around the altar. There is plenty colour in Burges’s interior. The large rose-type stained glass windows provide a colourful array of light inside the church. The great piers, which support the roof are of grey-brown Stourton stone.

The reddish columns are of Cork red marble. The sanctuary explodes in many colours – green and red columns, gilded capitals, and a ceiling patterned in red, blue, gold, white and green.

In regards to the interior fittings, Burges accumulated a coterie of artists and craftsmen who under his direct control were responsible for stained glass, woodwork, mosaics and metalwork.

Steeped in folklore, the golden angel, the gift of William Burges adorning St Finbarre’s Cathedral is an impressive addition. Put there to make one think of the heralding of the end of the world, it also highlights the deeply rooted connection with rich ecclesiastical history on the site.

The mosaic pavement of the apse was designed by William Burges and made by Burke & Co from Lonsdale’s cartoons in Paris. It is interestingly to note that Italian artists from Udine were employed, using marble segments, reputably mined in the Pyrenees Mountains, which form the border of France and Spain.

There were 1,260 pieces of sculpture planned for the cathedral and Burges personally designed each one. Mr Nicholls modelled everyone in plaster, except for the figures in the western portals and the four Evangelistic emblems around the rose window. Everyone was also sculptured insitu by R McLeod and his staff of local stone-masons. Great care was taken to make sure that every piece was of a high standard. This was a process that was to take a decade.

The organ, dating from 1889, is located in the north transept. It was built in 1870 by William Hill and Sons and is the largest cathedral organ in Ireland and the only one in a pit in Britain or Ireland.

VISIT the Cathedral for more information or take a guided tour or log onto their website here: St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, Cork, Ireland (webs.com)

Watch and listen to a commentary on the building by Dean Nigel Dunne:

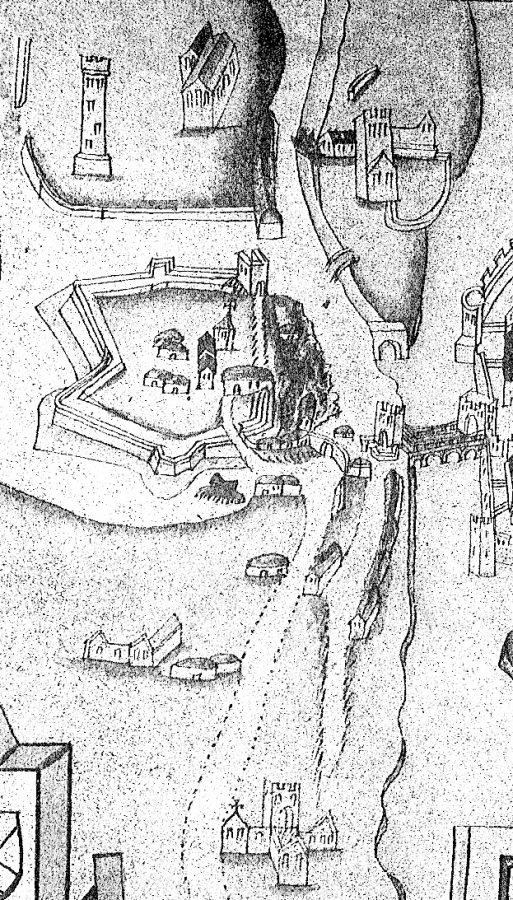

Viking Age Cork – Keyser’s Hill:

The advent of Norwegian Vikings in 820 A.D. and Danish Vikings circa c. 914 marked the early origins of Cork as a port. These new invaders did start off by raiding the monastery on the hillside but soon turned their attention to neighbouring powerful and wealthier political kingdoms in Munster. One such local kingdom was that of Fir Maige in southern Munster.

The Norwegians and Danes did decide in Ireland and settlement bases were established. Unfortunately, todate, the database of information regarding a Norwegian and Danish settlement at Cork is historically and archaeologically deficient compared to excavations conducted at Waterford and Dublin in the last number of years.

Nevertheless, it is known that a Danish area of settlement was located south of the site of FinBarre’s monastery on the southern hillside extending from what is now present day Frenches Quay- Barrack Street area to the area of Georges Quay.

From the few historical records available, it is known that this settlement was bounded by the monastery on one side and a cross called Carmelaire on the other; it possessed a little harbour reflected in the present name Cove Street and a central routeway which led to a church named Sepulchre. St. Sepulchre Church was located in the area of present day of Douglas Street. In fact, St. Sepulchre is alleged to be one of four Christian churches founded in the Late Viking Age Cork, circa 1,000 A.D. The other four included St. Mary del Nard, St. Michael’s, both of which were located just west of present day Barrack Street. St. Brigid’s was located in the present day area of Deerpark, in Turners Cross. Dedications to Michael and Brigid are also known in other Scandinavian towns such as Dublin, Wexford and Waterford. The fourth church was that of St. John the Evangelist whose location existed somewhere in what has become the central campus of University College Cork.

On the monastery side there is still Viking placename evidence in the form of Keysers Hill. The name Keyser is Scandinavian in origin and means the “path leading to the quayside”. This suggests the existence of trackways through settlement and associated basic quays adjacent to the River Lee.

The second habitation zone was located on an adjacent marshy island, an area, which is now occupied primarily by Beamish and Crawford, South Main Street, Hanover Street and Bishop Lucey Park. An enclosing fortification either of timber or stone encompassed the island settlement and the entrance was in the form of a bridge, called “Droichet”, which is similar to the Irish derivation “droichead” meaning bridge. Since 1977, there have been several archaeological excavations in the South Main Street area, which have revealed Danish Viking age material.

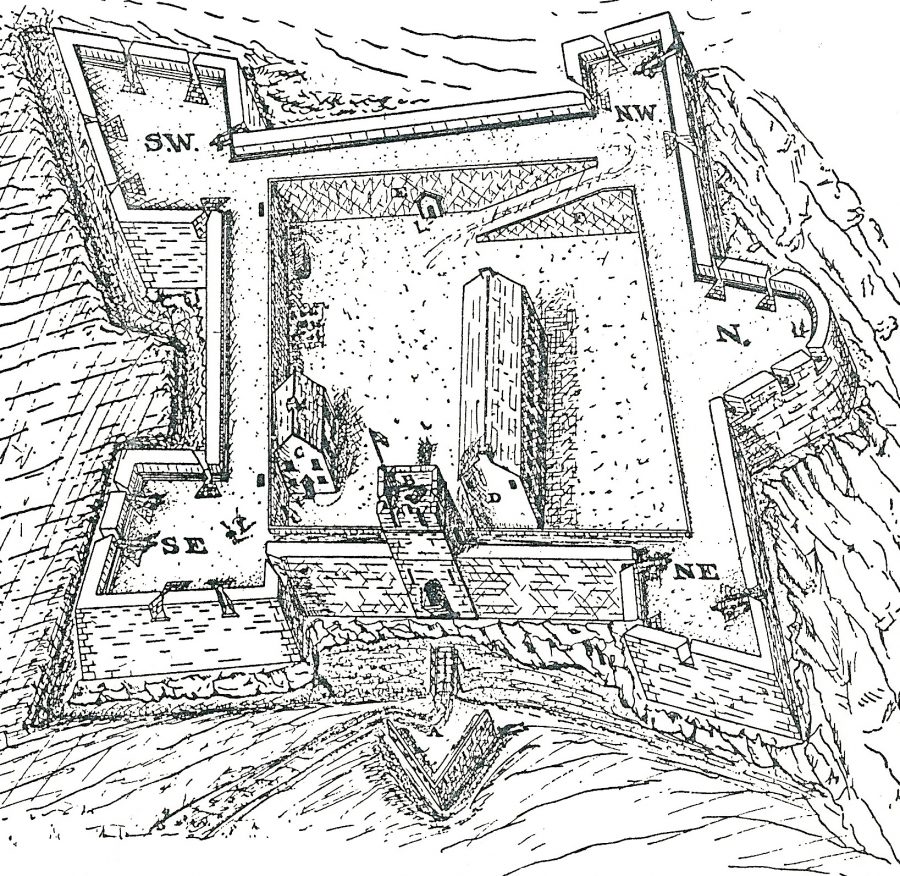

Elizabeth Fort:

The star shaped fortification of Elizabeth Fort named after Queen Elizabeth Ionce protected an English garrison in Cork and became a distinct landmark in the immediate southern suburbs of seventeenth century Cork. Constructed in 1601, the fort protected the walled town of Cork from attack from Gaelic Irish natives and Spanish invasion.

In January 1590, the order was given by Queen Elizabeth I to construct star-shaped forts outside the town walls of each major Irish coastal walled town, in particular at Waterford, Limerick, Galway and Cork. Cork’s Elizabeth Fort was erected on top of a rock outcrop and early representations of the fort show that it was an irregular fortification in design with stone walls on three sides and an earthen bank facing the walled town. To enter into the interior, one had to cross a drawbridge through a portcullis gate and past a gate-house. None of the original fort can be seen today.

In 1603 as a result of Cork’s refusal to honour the crowning of the Catholic King James I, the fort was attacked by an unnamed faction of rebel Irish figures, who considerably damaged the main structure. The Irish rebels stole the guns of the fort and brought them arms into the walled town to cause civil unrest. Nevertheless due to the presence of the Lord Deputy of Cork, Lord Mountjoy and his forces, they seized the city and made the citizens unwillingly rebuild the fort. The new structure received the name “New Fort”.

The Siege of Cork in September 1690 tested the strength of the fort immensely. In short, the Irish possessed Elizabeth Fort and the English had to dominate at least two tall adjacent buildings, Red abbey and St. FinBarre’s Cathedral to rain down shots on the Irish in the area in order to attain surrender. It is unfortunate that much of the documentation describing the layout and rebuilding of the fort from the early 1700s to the present day has been lost. All that is known is that the encompassing star-shaped bastion remained unchanged. It is known that in 1719, Elizabeth Fort became a British military barracks and catered for seven hundred men. An additional barracks known as Cat Barracks (established in 1698) existed nearby. The external of Cat Barracks are visible today.

In 1806, due to the construction of the ‘New Barrack’s’ to the north east of the city (now Collin’s Barracks), the barracks within Elizabeth fort was altered to that of a Female Convict Prison. In the late nineteenth century, the fort was used as a station for the Cork City Artillery Militia.

In 1920-21, it was occupied by the Royal Irish Constabulary and handed over to the Provisional Irish government. A year later in 1922, it is known that the existing interior buildings of the fort were burned down by Anti-Treaty forces. The walls and bastions of the fort were undamaged. A few years later, a Garda Station was set up in the interior of the fort and today is still in operation.

Elizabeth Fort remains one of Cork’s most historic gems. Never been excavated, Elizabeth Fort has a wealth of stories waiting to be discovered and to be told.

Listen to Kieran’s RTE Radio Morning Ireland interview on Elizabeth Fort, 8 January 2014 http://soundcloud.com/morning-ireland/elizabeth-fort-in-cork-is

Watch a short news report from RTE on 31 July 1986 by Tom MacSweeney,

Click here: RTÉ Archives | Collections | Elizabeth Fort Cork (rte.ie)

Watch a short film from the Irish Examiner with journalist Eoin English on Elizabeth Fort and the handing over of the fort by the OPW to Cork City Council, 2014:

St Nicholas Church:

St. Nicholas Church is located on the western end of Abbey Street behind the tax office on Sullivan’s Quay and was erected initially in honour of the Anglo-Norman victory over the Danish settlers in Cork in 1174. The Anglo-Norman church of St. Nicholas was registered by its clergy in 1270 and granted by the Bishop of Cork to St. Thomas, Abbey, Dublin. Nearly four hundred years later, this church still stood and had managed to stand the test of time. Severe damage was caused to St. Nicholas Church during the siege of Cork in 1690. It was only in 1720 when funds were allocated by the Protestant Bishop of Cork, Peter Browne, that a new St. Nicholas Church was built. Indeed, the finance for its construction came from the taxing of coal that was imported into Cork for domestic purposes.

Construction work on the new church began in 1720. In mid June 1721, the Town Chamberlain paid £100 out of the coffers of the Corporation to Mr. Archdeacon Ayers, the head builder of the church venture. Misfortune occurred again on 20t June 1726 when the eastern end of St. Nicholas Church was greatly damaged by thunder and lightning. Repairs were duly initiated.

The Church is now the home of the offices of the Probation Office.

Red Abbey:

The central bell tower of the church of Red Abbey is a relic of the Anglo-Norman colonisation and is one of the last remaining visible structures, which dates to the era of the walled town of Cork. Invited to Cork by the Anglo-Normans, the Augustinians established an abbey in Cork, sometime between 1270 A.D. and 1288 A.D. The Abbey was dedicated to the Most Holy Trinity but had several names, which appear on several maps and depictions of the walled town of Cork and its environs.

For example, in a map of Cork in 1545, it was known as St. Austins while in 1610, Red abbey was marked as St. Augustine’s. In medieval times, an abbey comprised a church, which was divided in two by a central tower. The tower divided the altar area from the public area and connected to the church area were religious and domestic rooms. In the case of religious rooms, these included a sacristy, a reading room or chapter room. In the case of the domestic rooms, these took the form of a kitchen, refectory, cellars and a dormitory. Apart from been connected to the church these rooms would also encompass the abbey’s central garden and walking area known as the cloister garth.

Sometime in the years 1687 to 1690, Ignatious Gould, Merchant and property owner bought a portion of Red Abbey from the friars. The rest of the portion was eventually given to Othowell Hayes of Ballinlough in the southern suburbs of Cork. It was at this point in time, circa 1700 that the friars left.

In 1690, Red Abbey was used as a base by the English to fire cannon balls into the City during the English siege of Cork. The siege sought to suppress the Gaelic Irish uprising in the city and its association with the Catholic expelled English King, James II.

In the eighteenth century, the Augustinian friars established a new friary in Fishamble Lane, now renamed Liberty Street. In the mid eighteenth century, parts of the buildings of Red Abbey were used as part of a sugar refinery. This refinery was burnt down accidentally in December 1799. Since then, the friary buildings with the exception of the tower have survived in piecemeal form. The tower is maintained by Cork City Council who were donated the structure by the contemporary owners in 1951 and also own other portions of the abbey site.

A number of archaeological excavations have been completed at Red Abbey in the last twenty-five years. The first took place in May 1977, when a section to the west of the remaining tower, now an amenity square was excavated. Twenty-five burials were uncovered skeletons were discovered and these showed burial spanning a number of years.

Today, the tower of Red Abbey approximately thirty metres high is one of Cork’s most important protected historic structures. The remaining tower cannot be climbed but medieval architecture can still be on the lower arch of the structure and in the upper windows. The adjacent street name of Red abbey Street also echoes the bye-gone days of the extensive medieval abbey.

South Chapel:

The present South Chapel is the fourth of which we have knowledge. The first existed in 1635 and was ruined by 1702. The site of this is not known, but may have been in the Cat Lane – Barrack Street district. About 1702 the second was built near Douglas Street in the precincts of the South Presentation Monastery. This was a thatched church, which was burned in 1727.

On the same site, the third church was built in 1728. It is described in the “Report on the State of Popery (1731) as “a slated Mass-house in the suburbs”. The present building was built in 1766 by Daniel O’ Brien, O.P., who was Parish Priest at the time. He retired from active work to his convent in 1774, and died in 1781.

The South Chapel, originally a mass-house consisting of a nave and chancel, was built in the Georgian style of the period. Whether the North transept was built at the same time is not known. The masonry is identical with that of the nave. The south transept was built in 1809, and its dimensions do not coincide with those of the North Transept. The altar contains the Dead Christ, by John Hogan (1806-1870), the noted Cork sculptor. The Crucifixion, behind the altar, is said to have been painted by another Cork artist Mr. John O’ Keeffe. A well-executed monument to the memory of Catholic Bishop, Dr McCarthy is in the south transept. The monument is in white marble and represents Dr. McCarthy as lying on the death-bed and receiving Viaticum from a bishop – in this case from Catholic Bishop of Cork, Dr. Moylan.

Altar of South Chapel, Cork, present day (Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

The Dead Christ by John Hogan, beneath altar of South Chapel, Cork, present day (Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

Nano Nagle Legacy:

The Presentation Sisters were established on Douglas Street by North Cork woman, Nano Nagle in 1776. Amidst the backdrop of influential charity schools in the city for Protestants, Nano Nagle particularly wished to provide education and instruction in the Catholic faith. Her first school was in a little rented cabin on Cobh Street, now Douglas Street and she provided food and medicine for the needy as well.

Such was Nano Nagle’s presence in the city that she established her own congregation of sisters in 1776 known as the “ Sisters of the Charitable Instruction of the Sacred Heart of Jesus “. Nano Nagle died on the 26th April 1784, aged 65 years, and her grave can be visited in the garden of the South Presentation Convent.

Check out Cork’s fab Nano Nagle Place, https://nanonagleplace.ie/heritage-centre/

Watch a short film on Nano Nagle Place:

South Presentation Convent:

In late nineteenth century Cork, the division between the middle and poorer classes became larger. In general, the rich got richer whilst the poor got poorer. Emigration of the poor after the Great Famine became a large problem in Cork. The city became one of the principal ports that witnessed large numbers of people boarding ships to America, Australia and Britain. Between 1851 and 1871, circa 266,000 people departed from Cork port.

A survey of the lodgings of Cork City, together with the National Census of Ireland, both completed in 1851 revealed deplorable conditions. Both reports detail overcrowded city parishes, with a total municipal population of 85,732. The three most overcrowded parishes included city centre locations – Holy Trinity, St. Paul’s and St. Peter’s. On average, ten people lived in each house in these areas. Only one third of those aged, between five and fourteen, attended Cork schools. One third of the population in 1851 were unable to read or write.

For the lower classes, there were several free public schools in late nineteenth century Cork, the most notable of which was operated by the Christian Brothers and known as the North Monastery, with branch establishments at Blarney Street (northside) and Sullivan’s Quay (southside). Together, over 2,000 boys of poor backgrounds received an excellent education.

A similar institution was operated by the Presentation Brothers under the name of the South Presentation Monastery, which likewise had two branch establishments, one known as the “Lancastrian” Schools and another as the “Greenmount” Schools, both established within the 1860s to educate the poorer classes on the south side of the city. Girls were educated in reading and writing in the North and South Presentation Schools run by the Presentation Sisters and St. Marie’s of the Isle, run by the Sisters of Mercy.

Evergreen Buildings:

In 1875, the “Artisans and Labourers Dwellings Improvements Act”, and later the Housing of the “Working Classes Act” of 1890, detailed the importance of eradicating tenement or slum housing. At this time no large financial aid was available to carry out large-scale clearance. However, Cork Corporation did make an effort. In 1886, 76 new houses were built in Blackpool on the site of an old cattle market. Named the Madden’s Buildings, these new houses were to set the scene for a further three housing schemes before the turn of the 1900s.

Apart from the Corporation, a group named the Cork Improved Dwellings Company also built housing in the city. This was a group, which favoured the idea of British philanthropic industrialists building workers’ housing, the idea being that a happy worker would be a more productive one. Housing schemes such as Evergreen Buildings, Prosperity Square, Prosperous Place, Industry Street were built adjacent to Barrack Street.