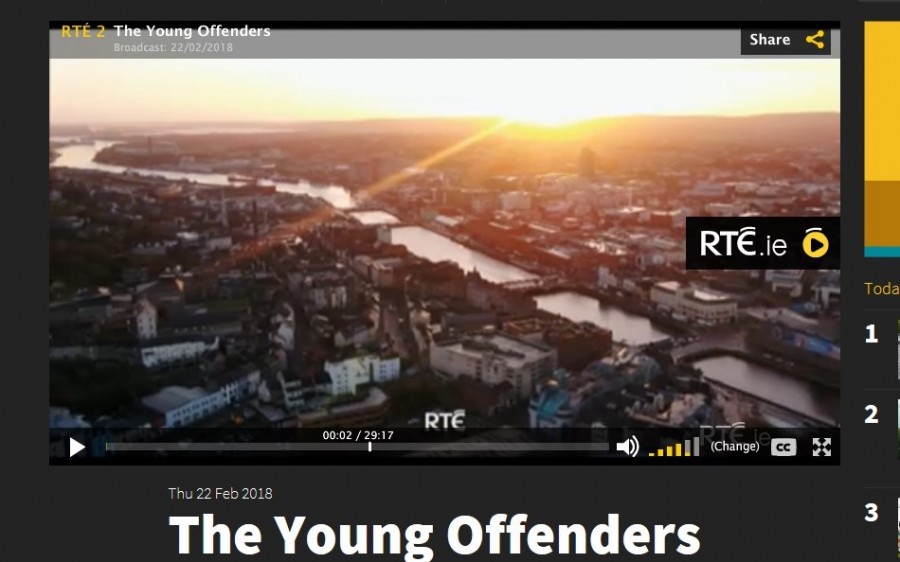

In The Young Offenders, Cork provides the backdrop of the adventures of Jock and Conor. Daniel Jordan, Director of Photography, introduces the scenery and nuances of Cork’s landscapes.

Cork has a north west European and an Eastern Atlantic port story. Located in the south of Ireland, it is windswept by tail ends of North Atlantic storms, which consistently drench the city and rural areas with wind and rains – but they leave to showcase a very photogenic urbanity with amazing sunsets on the river channels and a resilient green agricultural hinterland and chiselled raw coastline. Cork’s former historic networks and contacts are reflected in its the physical urban fabric – its bricks, street layout and decaying timber wharfs. Inspired by other cities with similar trading partners, it forged its own unique take on port architecture.

Cork has a soul, which is packed full of ambition and heart. They say the best way to get to know a city is to walk it. Get lost in Cork’s narrow streets, marvel at old cobbled lane ways, photograph old street corners, look up beyond the modern shopfronts, gaze at clues from the past, be enthused and at the same time disgusted by a view, smile at interested locals, engage in the forgotten and the remembered, search and connect for something of oneself, thirst in the sense of story-telling – in essence feel the DNA of the place.

The Young Offenders, Series I showcases a number of historic locations.

Episode 3:

3.1 View from Shandon:

The name Shandon comes from the Irish word ‘Sean Dún’, which means old fort and it said to mark the ringfort of the Irish family, MacCarthaigh who lived in the area c. 1,000 AD. The site of this fort is now marked by the Firkin Crane, a dance development centre. St. Anne’s Shandon was built in 1722 to replace the older and local church of St. Mary’s, Shandon, which was destroyed in the siege of Cork in 1690 by English forces.

The Shandon Quarter witnessed the development of economic drivers for the city in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Once the home of the city’s cattle butcheries and the Butter Market, and the spin off industries of both, thousands of people were employed here. The area is also home to some of Cork’s historic landmarks from the early eighteenth century Protestant St Anne’s Church, Shandon and graveyard to the beautiful interior of SS Mary’s and Anne’s Roman Catholic Cathedral.

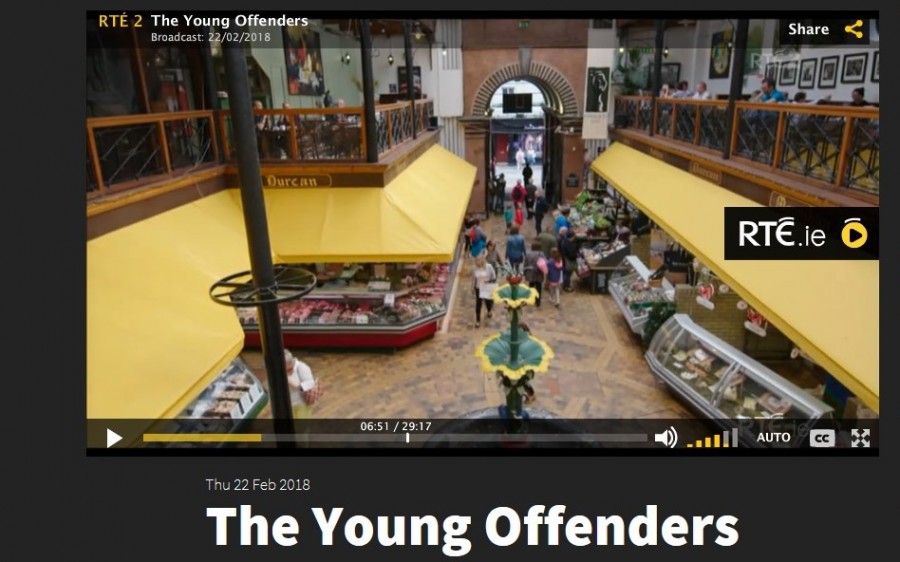

3.2 English Market:

The English Market was opened in 1788 and was known then as the root market. Today Corkonians know the market under several names: The Princes street market, the English Market, the Grand Parade market or some call it ‘de market’. By the mid-1800s, the market had fallen into a state of disrepair. In 1862 the market was rebuilt under the direction of architect Sir John Benson. the renovations were considered very successful. the market has suffered two fires, one in 1980 and the other in 1986. After the 1980 fire, the market was again renovated at a cost of £500,000 and once again it was considered a great success, some of the original features were retained even. The fire of 1986 caused an estimated cost of £100,000 worth of damage. nevertheless, the market was again repaired. A characteristic of the market is the selling of tripe and drisheen, which are both traditional foods and have been eaten in Cork for centuries. Drisheen is extra special as it is indigenous to Cork.

3.3. North Mall & the Franciscan Abbey:

A Franciscan Abbey was founded in 1229 (on the site of the North Mall) by the Irish chieftain, Dermot McCarthy, King of Desmond who was loyal to the English monarch at the time, Henry II. In April 1540, a royal survey conducted by officials, sent by the English monarch Henry VIII, detailed that the site of the abbey comprised one hall, one kitchen, one cloister, six large dormitory chambers, six cellars, a water mill, a fishing place for salmon, a salmon weir, and several plots of land in the townland of “Teampal na mBrathar” or “Church of the Monks”. Placename evidence also suggests that the friars possessed a chapel in the northern suburbs overlooking the walled town known as “Cilleen na Gurranaigh” or” The Little Church of the Groves”. In time, this placename changed to “Gurradh na mBrathair” or “Friars’ Grove”, which is highlighted in the present day northern suburb of Cork City known as Gurranabrahar.

The Abbey buildings still existed in the early half of the 1700s but did disappear over time under eighteenth and nineteenth century housing on the North Mall. Perhaps, the most known remaining feature of the North Abbey is its water well, which can still be viewed in the Franciscan Well Brewery. In the years 1730 to 1750, evidence shows that the Franciscan Order moved from the North Mall to Broad Lane, now marked by the St. Francis Church, built in 1953 on Liberty Street.

3.4 Kyrl’s Quay & Medieval Cork (left of aerial image)

The Anglo-Normans made significant changes to the landscape of the city. Between the 1170s and 1300s, a stone wall, on average eight metres high, became the new perimeter fence for the old Viking settlement area on the island, which was accessible via a new drawbridge built on the site of the Viking bridge, Droichet. Beyond this wall, a suburb called Dungarvan (now the area of North Main Street) was established on a nearby island. There are only scant historic records detailing the existence of Dungarvan.

It is known that the suburb of Dungarvan was connected to the walled island Anglo-Norman town by a bridge. A water mill existed between the walled town and Dungarvan. Three excavations in the past fifteen years have revealed evidence for the existence of Dungarvan. In 1983 a thirteenth-century mural turret was found on Corn Market Street, while in 1994 excavations on the site of Kyrl’s Quay Shopping Centre, uncovered a quay wall in mid-thirteenth century deposits. It was at Kyrl’s Quay too that excavations also yielded evidence of the development of street frontages and burgage plots. These plots dated to the thirteenth century and extended from the street frontage back towards the town wall.

3.5. Former Wise’s Distillery, North Mall:

The house at the junction of the North Mall and Wise’s Hill was the residence of the distiller Francis Wise, after whose family the hill is named. It is a detached five-bay three-storey former house, built c. 1800, now in use as a university building. The building retains interesting features and materials, such as the timber sliding sash windows, wrought-iron lamp bracket arch, and interior fittings. The North Mall distillery was established on Reilly’s Marsh around 1779, and by 1802 the Wise brothers were running the firm. Whiskey production was another significant industry in Cork from the late eighteenth century.

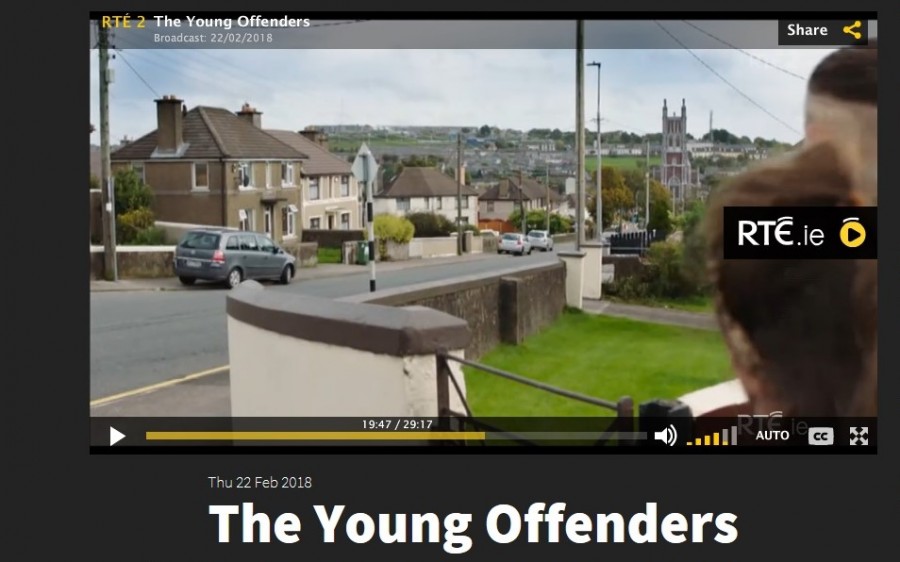

3.6 St Finbarre’s Cathedral (right):

The first known settlement at Cork began as a monastic centre in the seventh century, founded by St Finbarre. This is now marked by the late nineteenth structure of St Finbarre’s Cathedral. it stands tall proud in its ecclesiastical heritage and also imbuing the city and wider region with a need for community to bring people together and to invest physically and morally in such structures. Hence, Cork has a myriad of church buildings with different styles from different times when such buildings were called upon to impart new messages about their contribution to the city.

This is also a corner of Cork filled with iconic histories, which defined the early history of Cork and instilled into the urban space cultural narratives of legacies of monks, Viking marauders and English Plantation fortresses. It is home as well to Cork’s UCC, Crawford College of Art and St Marie’s of the Isle. Education and learning play a huge part in this quadrant of the city. Scramble up Barrack Street and explore its multiple laneways, many dating back over 400 years and all adding immense historical character into the urban landscape.

3.7 Sunday’s Well (left):

Sunday’s Well was a famous landmark through the ages and the adjoining district took its name from the well. In 1644, the French traveller M de La Boullaye Le Gouz, visited Ireland. In the account of his journey he writes: “A mile from Korq [Cork] is a well called by the English, Sunday Spring, or the fountain of Sunday, which the Irish believe is blessed and cures many ills. I found the water of it extremely cold”. Charles Smith in his second volume of his History of Cork, mentions “a pretty hamlet called Sunday’s Well, lying on a rising ground…here is a cool refreshing water, which gives name to the place, but it is hard, and does not lather with soap”. Antiquarian Thomas Crofton Croker described the well as well; “Sunday’s Well is at the side of the high road, and is surrounded by a rude, stone building, on the wall of which the letters HIS mark its ancient reputation for sanctity. It is shadowed over by some fine own ash trees, which render it as a picturesque object”. Writing later still John Windele says of the well; “Early in the mornings of the summer Sundays may be seen the hooded devotees with beads in hand, performing their turrish or penance, besides this little temple”.

The historic landmark is no longer visible. At the beginning of 1946, the adjoining roadway was widened and improved, it was necessary to remove the stone building covering the well, and to run the road over the well. However, to mark the site, the stone tablet bearing the inscription, “HIS, Sunday’s Well, 1644”, which had been on the building, was placed on the wall adjoining the road. Rounds are no longer paid there.

3.8 Daly’s Bridge:

Built in 1926, Daly’s Bridge spans a section of the river which is surrounded by greenery. One has Fitzgerald’s Park on the south side and several landscaped gardens on the north side. Prior to 1926, it had been suggested many times that a footbridge should be built in the locality in order to enhance the area. It was therefore decided by the Corporation to go halves on building a bridge with a Mr James Daly who was a butter merchant in the city. A decision was made to construct a suspension bridge which would be supported at intervals across the river with the aid of anchored cables. A pedestrian walkway consisting of timber planks was also constructed. The building contract was awarded to a London based steel company owned by a Mr. David R. Bell. Another major feature of Daly’s Bridge is its nickname. It is more commonly known as the “Shaky” Bridge. It attained the name due to the fact that a large number of people used the bridge to go to and from Gaelic matches in the Mardyke. Consequently the bridge would shake with the masses of people walking across it.

3.9. St Finbarr’s Cemetery:

Since mid-November 1867, this beautiful cemetery has become an iconic space of reflection, art and architecture. Its back story is a long and complex one and this article attempts to shine some light on it.

By late November 1866, the Corporation’s cemetery committee and the Corporation selected 15 acres of flat and rectangular ground at Glasheen. The cost would be £600 to the occupying lease-holder and £125 to the tenant who was growing crops on the site. The Cemetery Committee prepared to receive proposals for building a boundary wall, to enclose the land taken by the Corporation for the cemetery. The ground combined the various qualities required for a cemetery as the soil was dry, sandy and deep. A plan of the intended cemetery was prepared by Sir John Benson, the city engineer. The ground was to be laid out much on the plan of Glasnevin in Dublin, and planted with ornamental shrubs, and divided by walks.

A fourth of the entire new cemetery space was to be allotted for the burials of persons of the poorer classes who would not be able to pay the charge to be made for interments. Two thirds of the cemetery were to be reserved for Roman Catholics and one third for Protestants. Each religion was to have a mortuary chapel for its separate use. By mid-January 1867, the Cemetery Committee sought tenders from competent parties for the erection of two chapels on the grounds of the new cemetery. In late April 1867, the Committee sought proposals from competent parties for the building of a registry office at the entrance to the cemetery.

3. 10. St. Mary’s and St. Anne’s North Cathedral (right):

The present Cathedral of St. Mary’s and St. Anne’s is the fifth church on the site since the early 1600s (1624, 1700, 1730, and 1808). The story of the present day structure is as follows. In 1820, an immense fire greatly damaged the fourth cathedral so much so that it was really the skeleton structure of the burned cathedral that survived. However all was not lost and shortly after, the bishop of that time, John Murphy delegated to architect, George Pain, the rebuilding of the then 12 year old cathedral, inside and outside. George Pain was also responsible for the design of buildings such as Holy Trinity Church, St Patrick’s Church and Blackrock Castle.

In 1868, at an influential meeting of Catholic citizens, convened by then Bishop of Cork and Cloyne, Delany, certain alterations and improvements to the church were debated. The plans prepared by Sir John Benson were discussed and adopted. Early work commenced on the rebuilding of the buttresses, re-arrangement of the windows, and addition of the parapet and minarets to the southern aisle of the nave. By July 1869, many of the outer features were completed under the contractor, Mr R Evans, Union Quay including the parapets, spire and minarets. However, this was when the project ran into financial difficulty and the remaining features of Bensons’ proposals were never carried out. Instead of the proposed spire, four pinnacles were designed and constructed. At a height of one hundred and fifty–two feet, the present day cathedral stands ten feet higher than the adjacent tower of St Anne’s Church, Shandon.

3.1 1 Corn Market Street:

A corn market was constructed in 1719 overlooking a square that was located on filled-in portion of a channel of the River Lee (Coal Quay). Unfortunately, the name of this square is not recorded, but it was located on what is now Corn Market Street. Over the centuries, the square grew to be the traditional central market area of the city. It would have been thronged with dealers and customers, purchasing anything from a needle to an anchor. Several stalls still operate here today. During 2011-2012, over €1 million has been allocated by Cork City Council for the refurbishment of Cornmarket Street. The street, underwent a massive facelift to give it the feel of a European outdoor market.

3.12. Pope’s Quay:

In 1697, the Dominicans who were invited to Cork by the Anglo-Normans in the early 1200s were obliged to leave their abbey, the site of which is now Crosses Green Apartment complex due to the fact that their lands and buildings were confiscated as a result of the politics of the day. The Dominicans consequently moved to a laneway (unknown today) off Shandon Street and established a new set of religious buildings for their community of over fifty priests. It was here in the early 1800s that a Dominican named Father Bartholomew Thomas Russell first came up with the idea of building Saint Mary’s church on Popes Quay, an open site available for redevelopment.

3.13. Biodiversity in Cork City:

Cork supports a wide range of plants and animals. Some are common species, some rare, some legally protected and some are seen as pests. The green spaces of the city provide havens for species more usually found in rural situations whilst the structures of the city, the walls and buildings, provide homes to specialist species which specialise in living in cities.

Mammals such as the otter are not usually associated with cities but Otters are quite common along the River Lee throughout its course through the city and people have been lucky enough to see them swimming in the river from busy city centre bridges on occasion. The shoreline from Blackrock around Mahon to the Douglas Estuary also provides excellent otter habitat.

The River Lee can throw up other surprises. Both Common and Grey Seals occasionally venture upstream from the harbour in pursuit of Salmon and Mullet; and who can forget the summer of 2001 when the Orcas came to town? Three of these magnificent whales swimming up the South Channel as far as City Hall on a busy Saturday night is not a sight that the inhabitants of many cities can claim to have seen.

Episode 4:

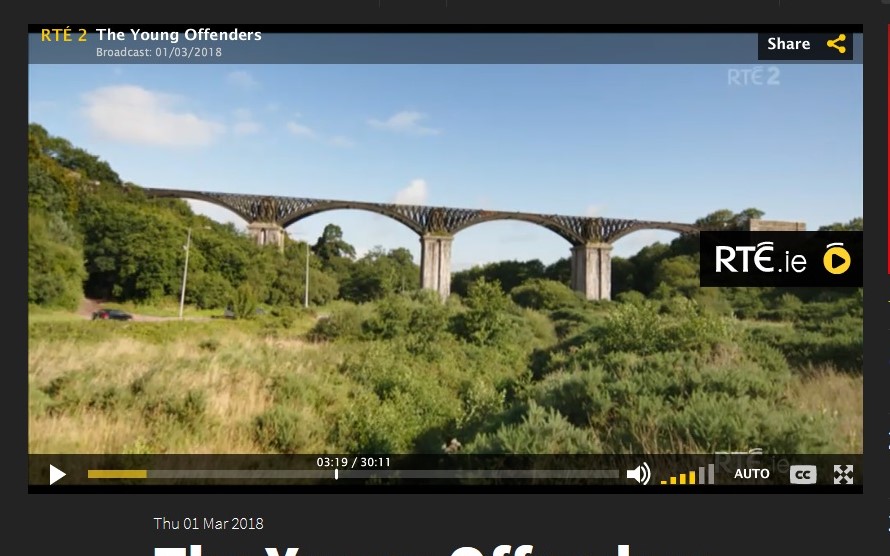

4.1 Chetwynd Viaduct

Engineer Charles Vignoles first proposed the idea of a railway that would connect Cork to Bandon in the Railway Commissioners report in 1837-38. In 1844, a provisional Bandon and Cork Railway Committee was established. The construction of the line was divided into six sections. Each section was the responsibility of different contractors. In 1849, due to financial difficulties, a decision was taken by the railway company to open the Bandon–Ballinhassig line as fast as possible. Subsequently, it was opened in June 1849. In September 1849, the company chose a tender of £87,000 for the Cork-Ballinhassig section of line. The contractors chosen were Sir Charles Fox and John Henderson.

The Cork Bandon Railway Project was an enormous undertaking. The main parts included; the longest railway tunnel in Ireland at Goggin’s Hill; The Chetwynd Viaduct; a short tunnel bridge under old Blackrock road near the Albert Quay Terminus; 21 cuttings; 19 embankments and 15 road bridges.

4.2 Farren Views, County Cork

In May 1953, work began at Carrigadrohid Dam, one of two dams on the River Lee funded by the Irish government, whilst in October 1956, the associated reservoir was filled in. Six hundred men were employed in the scheme, which required manual labour especially to prepare the rock faces and pour the concrete. Camps of temporary wooden buildings like a Wild West village, were created constructing a makeshift community to accommodate both Irish and French communities Once the gates of the dams were closed, 3,500 acres of land were to be flooded out and two new reservoirs emerged.

The Cork Harbour and City Water Supply Scheme. It is located a half a kilometre upriver from the ESB’s hydro-electric dam at Inniscarra. At the time of the Scheme’s construction, the facility was one of the largest public works undertakings ever built in Ireland. The Government approved IR£40 million in 1973. The total cost in 1982 was IR 48million. The scheme was infrastructural in its nature and was expected to cater for the water supply needs of industry in the Cork area well into 21st century. The Scheme in 2008 serves 110,000 persons in Cork all day every day.

4.3 Rosscarbery Bay Road, Co Cork

Rosscarbery is situated at the head of an extensive creek called Ross harbour, and occupies the summit of a hill. This place is observed in ancient ecclesiastical records under the appellation of Ross Alithri, signifying in the Irish language “the Field of Pilgrims”. It appears to have acquired great celebrity from the reputed sanctity of St Faughnan, Abbot of Moelanfaidh, in the county of Waterford, who flourished in the early part of the sixth century. He founded an abbey at this West Cork location, over which he presided till his death. A town gradually rose around the monastery, which subsequently became the seat of a diocese. In wars against English planters Irish clans such the McCarthys, O’Driscolls, and other Irish clans, bombarded the walls and a great part of the town was destroyed and rebuilt.

Rosscarbery consists principally of a square and four small streets. In the nineteenth century, the manufacture of coarse linen was carried on to a considerable extent and the inhabitants were chiefly employed in agriculture and in fishing. Near the town at one time were the extensive flour-mills of Mr Lloyd, in which more than 5,000 barrels of fine flour were annually made. The town is now a key location of Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way.

Episode 5

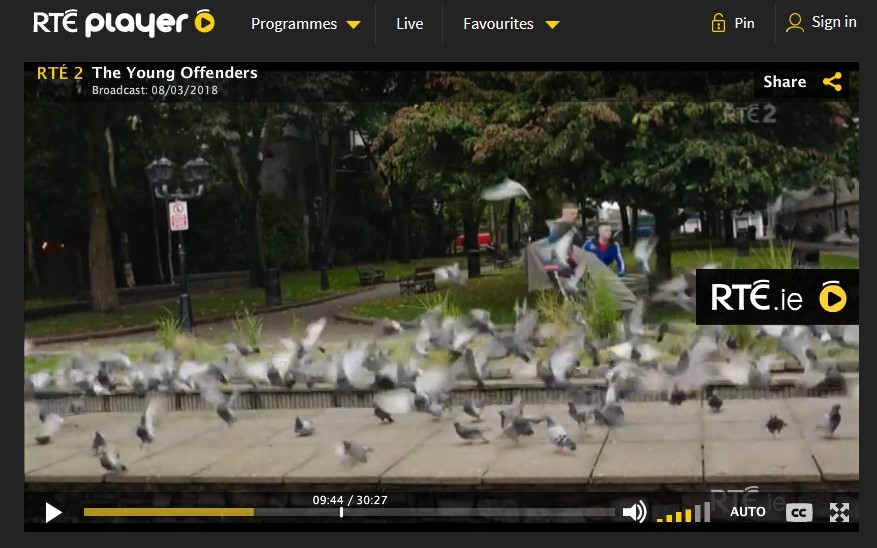

5.1 Bishop Lucey Park:

In 1984 / 1985, Bishop Lucey Park was created to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the granting of the first charter by King Henry II to the citizens of the walled town of Cork. Ironically, whilst preparing the ground for the park, a section of the imposing town wall was revealed. In general, much of the town wall survives beneath the modern street surface of the city and in some places has been incorporated into the foundations of existing buildings in particular buildings overlooking the Grand Parade.

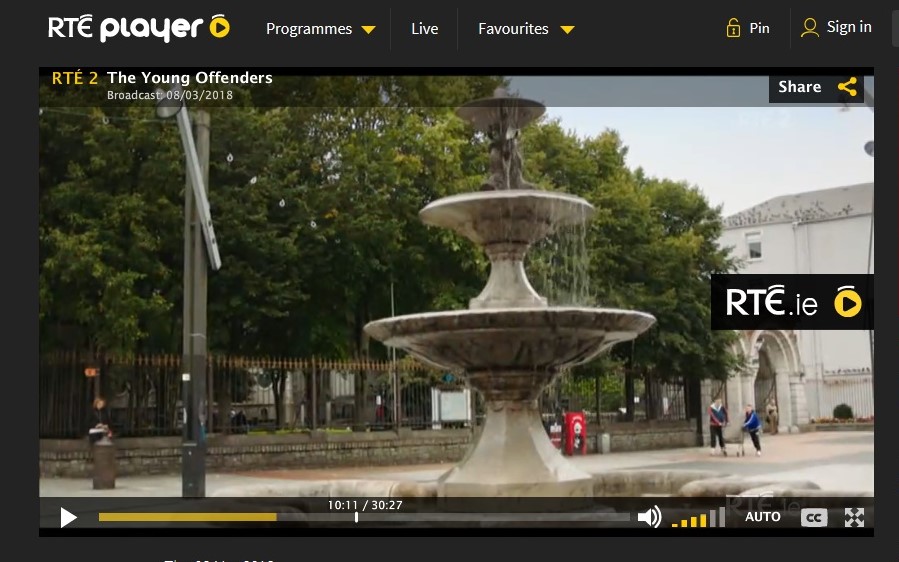

5.2 Berwick Fountain:

The fountain is named after Sergeant Walter Berwick who came to Cork to preside as chairman of the quarter session Courts in the city which were held every season in the 1850s. Berwick was a comical and popular man and came up with the idea of financing to the city a drinking fountain. He gave £350 to finance the cost of it, just before he departed from his position. Cork Corporation approved and Sir John Benson was given the honour of designing the fountain and took six months to come up with a plan.

The design included three cut stone basins, one over the other, surmounted by a cast iron one supporting dolphins and a boy with a little lily in his month out of which would spring a jet of water which would spring three metres above street level that would see water been pumped up through a central pipe that would spout out three metres from the ground.

However, it was six months again before the controversy of where to locate the fountain in the city and whether to add a garden to it was agreed upon. A garden was not added nor was the idea of a drinking fountain adopted. Nevertheless, On 27 August 1860, Cork Corporation laid the foundation stone of Berwick Fountain.

The builders never finished the fountain completely as one part did not arrive on time and is still missing today. Where the pipe protruding up at the top of the fountain, Benson’s figure of a little boy with a water lily in his mouth never arrived.

5.3 Holy Trinity Church:

Circa 1637, an order of Capuchins arrived in Cork. By the year 1741, a friary was founded behind Sullivan’s Quay. Here they constructed a chapel in 1771 in order to motivate the large local population to come to church. As time passed and another century began, the brethren was so immense that it was decided by Fr Theobald Matthew OFM CAP to build a larger church on the site and extending into a new area of land. The architect was George Richard Pain. The first foundation stone was laid on 10 October 1832.

5.4 Cork College of Commerce:

On 24 June 1935, in the presence of a large and distinguished gathering, Thomas Derrig TD, Minister for Education, laid the foundation stone of Cork’s new £60,000 Municipal School of Commerce and Domestic Science. The attendance included William T Cosgrave TD who travelled especially from Dublin for the occasion. The site and the foundation stone were first blessed by Rev J Canon Murphy, St Finbarr’s South Chapel. The Minister congratulated the architect, Henry Hill and the builder Sisks on the “admirable, yet simplicity of the building”. It was, he noted, a source of satisfaction to him to record that workmen and tradesmen of Cork played such an important part in the building of the school, and the materials and fittings would as far as possible be Irish.

5.5 Port of Cork:

Ever since Viking age time over 1,000 years ago, boats of all different shapes and sizes have been coming in and out of Cork’s riverine and harbour region continuing a very long legacy of trade. Port trade was the engine in Cork’s development. One hundred years ago, considerable tonnage could navigate the North Channel, as far as St. Patrick’s Bridge, and on the South Channel as far as Parliament Bridge. St. Patrick’s Bridge and Merchants’ Quay were the busiest areas, being almost lined daily with shipping. Near the extremity of the former on Penrose Quay was situated the splendid building of the Cork Steamship Company, whose boats loaded and discharged their alongside the quay.

5.6 Port of Cork:

In the late 1800s, the port of Cork was the leading commercial port of Ireland. The export of pickled pork, bacon, butter, corn, porter, and spirits was considerable. The manufactures of the city were brewing, distilling and coach-building, which were all carried on extensively. There were many large establishments in the timber trade, also many in which salt provisions were cured, and several tanneries, which produced leather of the choicest quality. There were also some salt, lime and chemical works.

The imports in the late nineteenth century consisted of maize and wheat from various ports of Europe and America; timber, from Canada and the Baltic; fish, from Newfoundland and Labrador regions. Bark, valonia, shumac, brimstone, sweet oil, raisins, currants, lemons, oranges and other fruit, wine, salt, marble were imported from the Mediterranean; tallow, hemp, flaxseed from St. Petersburg, Rig and Archangel; sugar from the West Indies; tea from China and coal and slate from Wales. Of the latter, corn and timber were imported in large numbers. Exports were principally pewter, whiskey, butter provisions, cattle, fowl, and eggs. Butter was the staple trade.

References:

Kieran McCarthy, 2016, Cork City History Tour (Amberley Books)

The Young Offenders TV Show, 2018: