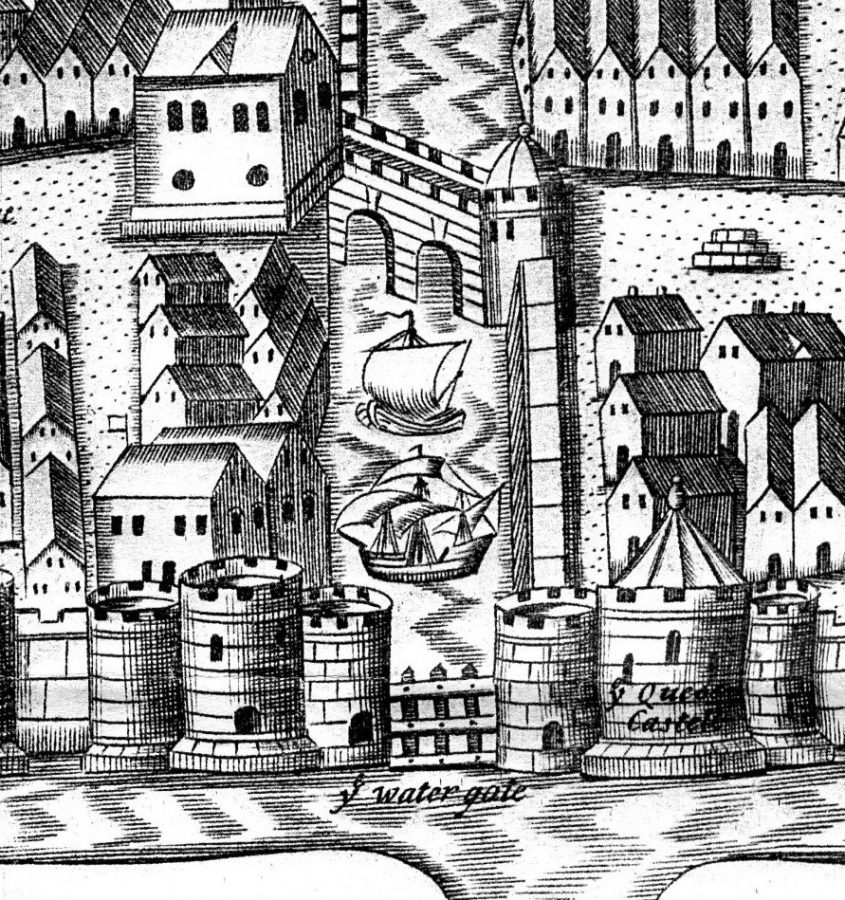

In the view of the English Crown, the walled town of Cork was an important strategic point to hold. The settlement lay adjacent to a large, deep and sheltered harbour with easy access to a rich agricultural hinterland, which meant that a substantial profit could be made through the export of produce.

Imports:

Circa 1300AD, several taxes are listed in subsequent Royal charters granted to the town, which refer to a variety of traded goods. Various cloths of English and French origin, foreign spices and vegetables were imported. A wide range of British ports handled these good, including Bristol, Carlisle, Southampton and Pembroke. They would have been brought to Cork along with pepper and onions from Italy.

There are numerous references to the importation of wine from France, the main ports being Gascony, Bayonne and Bordeaux. A large amount of the wine imported was re-exported to Scotland and Wales. This extensive wine trade is reflected in the vast amount of French pottery turning up on medieval archaeological sites in the city. Commonly known as Saintonge pottery, it comprised five types, the most being glazed jugs of a mottled green colour.

Exports:

The tax list also reveals which items were exported from Cork, primarily to English cities, such as Bristol, and to England’s new trading contacts in France and Northern Italy. The principle exports were oats, wheat, beef, pork, oatmeal, fish, butter, cheese, tallow (a form of animal fat) and malt.

Hides from cattle, horse, deer and goat, and wool were exported along with skins from small wild animals such as rabbit, fox, marten and squirrel. There is also the possibility that some live animals were exported, such as horses, cattle, sheep, pigs and goats. These were sent to English, Scottish and French ports.

In order to keep pace with the burgeoning econony, the first Royal mint was established in Cork in 1295. Little is known of this early coinage save that it was inscribed with the words, Civitas Corciae.

Port Expansion:

The fourteenth century saw further advances in the development of the walled town as an inner Atlantic port. In 1326, Cork became a staple town, in other words became an official market place (a ‘staple’) of hides, wools and woolfells. Dublin and Drogheda were also made staple towns. The regulations of a staple town were few, but aimed to concentrate the accumulation of revenue in one area deter tax avoidance by native or foreign merchants.

For example, citizens were only to wear cloth made in England, Ireland and Wales. The regulations primarily affected foreign merchants who could only trade in hides in a staple town. Native merchants too could only transact business in hides in a staple town. However, the regulations also benefited new merchants to the town as, upon arrival, they were afforded the King’s protection and if they were injured in any way, the inhabitants of the towns were held responsible.

Exports from Cork during the sixteenth century increased and included hides, wool and woodfells (skins with wool on them) to Bordeaux, Normandy and Dieppe in France and to Newport, Plymouth and Dartmouth in England. These raw materials were used to manufacture garments. Trading was also conducted between Cork and Bristol, Chichester, Minehead, Southampton and Portsmouth.

The return cargo from Bordeaux was wine, gold and silver. Other commodities exported were linen, mantles, wooden oak boards (for construction purposes), beef, mutton, fat, cloth, wheat, barley, herrings, salmon and wool. In addition, the export of preserved beef to Bristol in salted and packed barrels began in this era.

Imports during the sixteenth century covered a wide range of household items, including metals such as iron, brass, lead, pewter and tin. Other imported commodities included tar, glue, salt, hops, malt, cloth, soap, lard, starch, paper, cotton, earthenware and wooden boxes. Bristol and Plymouth were still the primary cities exporting to Cork, but new cities and towns, such as Exeter, began to export to Cork at this time. The wine trade with France remained intact, but Cork also began to import wine from Hamburg and Ferrol in North Germany.

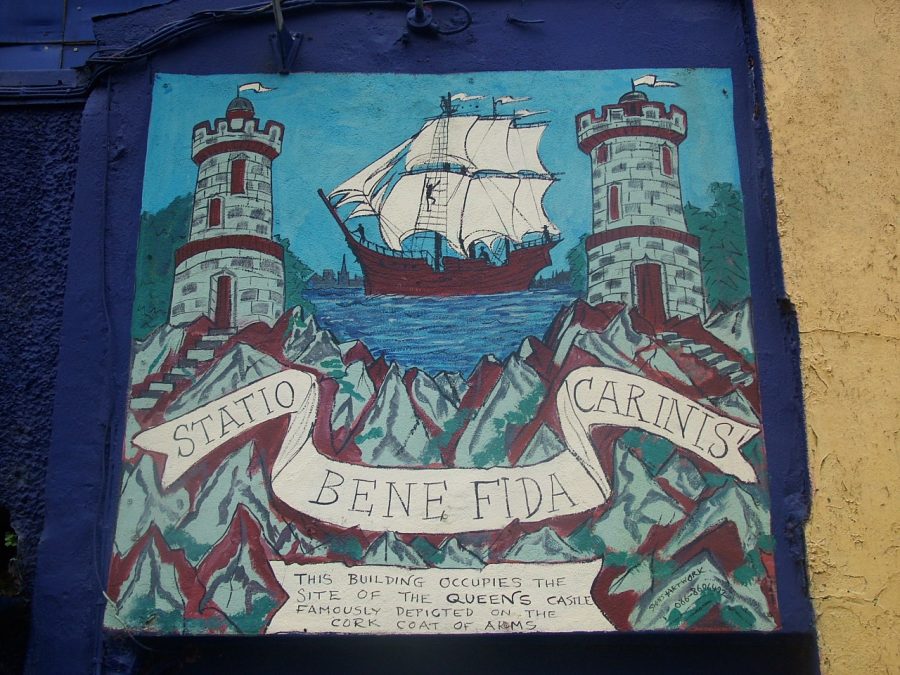

Read more and Explore more: 2d. Creating the Cork Coat of Arms | Cork Heritage