Starts at Lee Fields Weir, Cork

Below is a brief historical walking trail, which covers some of the topics on my physical walking tour. The information is abstracted from various articles from my Our City, Our Town column in the Cork Independent, 1999-present day, Cork Independent Our City, Our Town Articles | Cork Heritage

Sources: Abstracts from my Cork Our City, Our Town column on the River Lee Valley in the Cork Independent, 2006-2011 River Lee Index-In the Steps of St Finbarr | Cork Heritage

Introduction:

The River Lee defines Cork and its development. It is a core artery of the city and its western region. Many have crossed over the River’s bridges and have appreciated its tranquil hypnotic flow. It reflects vitality, engages the senses and presents a sense of mystery and secrecy. The River Lee is an accessible amenity that all can appreciate. At the Lee Fields, the notion of a divide between town and country are merged. Places such as its source in the Shehy Mountains or the pilgrim site of St Finbarre’s Gougane Barra and its mouth at Cork Harbour are connected.

The geography of the River valley from west to east is fractured and diverse. It is a beautiful landscape, a landscape transformed through the centuries by people. The diverse archaeological monuments from Stone Age tombs to the solitary Norman or Irish castle to the nineteenth century churches reflect the use of the River Lee Valley and its scenery and resources by its residents for the nourishment of the soul, living and surviving. The townland names of the ordnance survey reflect a human story especially the impact of human history on the natural landscape. It is an impact, which spans thousands of years.

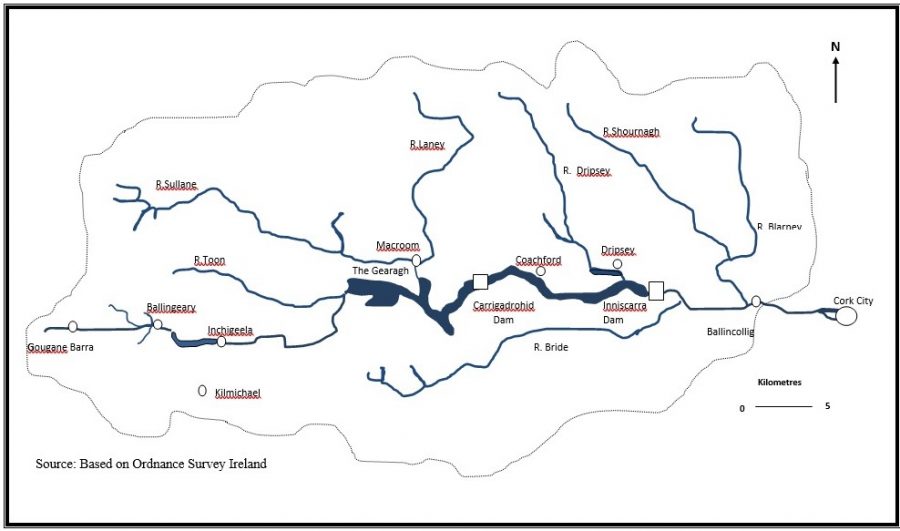

The area drained by the River Lee and its tributaries is about 400 square miles and has a number of tributaries. The principal drainage is from the north from the Derrynasaggart and Boggeragh Mountains whilst in the south the watershed is lower and supplies a lesser volume of drainage. The Lee can also be divided up into three well-defined stretches, the first is the highland and foremost rugged section from Gougane Barra to near Macroom. Here are the signs of glaciation with sharp limestone ridges and ancient lakes. The second section is the immediate area affected by the Lee Hydro Electric Scheme, encompassing Carrigadroid and Inniscarra Reservoirs to where the river meets the tidal estuary at Cork City’s Lee Fields. The gates of the two dams, were closed in 1956 by the Electricity Supply Board (ESB) and flooded out 3,500 acres of land.

The third section is the complex tidal estuary of Cork Harbour, which opens up from the city under historic bridges through islands such as Great Island and Spike Island through to Roches Point Lighthouse. Within each of the three sections, there are many local histories, many of which are written down; some of these are remembered within communities and some are forgotten about. The Lee for me tops Cork’s biggest secret and asset.

The Name of the Lee:

The origin of the name Lee is sketchy and legend reputedly attributes the name to an ethnic group known as the Milesians from Spain who reputedly arrived in Ireland several thousand years before the time of St. FinBarre. Legend has it that the Milesians acquired land in Southern Munster, which they named ‘Corca Luighe’ or ‘Cork of the Lee’ from Luighe, the son of Ith who attained the land after the Milesian advent to Ireland. The River Lee – An Laoi over the centuries has had many variations in its spelling. In early Christian texts such as the Book of Lismore, it is described as Luae. It has also been written as Lua, Lai, Laoi and the Latin Luvius. An entry in the Annals of the Four Masters in the year 1163 AD names the River Sabhrann. However, many scholars agree on the name Lee as the most common name of the River.

Old Cork Waterworks Experience:

The buildings, which stand at the Waterworks site today, date from the 1800s and 1900s but water has been supplied to the city of Cork from the site since the 1760s. A foundation stone today commemorates the building of the first pump-house, which was itself constructed on the Lee Road in the late eighteenth century.

It was in 1768, that a Nicholas Fitton was elected to carry out the construction work needed for the new water supply plan. The water wheel and pump sent the river water unfiltered to an open reservoir called the “City Basin” which was located on an elevated level above the Lee Road. This water was then pumped from here to the city centre through wooden pipes.

Officially opened in October 2005, the Lifetime Lab, a Cork City Council initiative funded by EFTA or the European Free Trade Association, was a welcome move in protecting and reinvigorating Cork’s heritage stock. As with every old city, the problem of what to do with a building whose function has expired is a nightmare for any owner. Formerly, the old Waterworks on Lee Road, the complex has been converted into a “lab” where visitors of all ages, especially children can enjoy a modern interactive exhibition, steam plant, beautifully restored buildings, children’s playground and marvellous views over our Lee Fields. The site is now named the Old Cork Waterworks Experience.

READ more here: Old Cork Waterworks Experience – Cork City Council

WATCH: A short history of the Old Cork Waterworks

Carrigrohane Straight Road:

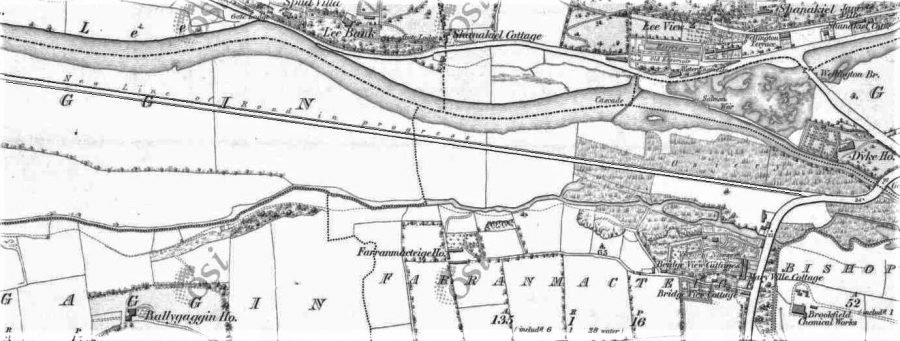

The history of Cork roads is diverse. Some were created as routeways for agricultural produce such as butter, some as famine relief projects and some were inspired as national symbols of the city’s and country’s place in the world. Since its creation in the early nineteenth century, Carrigrohane Straight Road has always played a key part in the life of the city as a western routeway.

Ireland’s Longest Building:

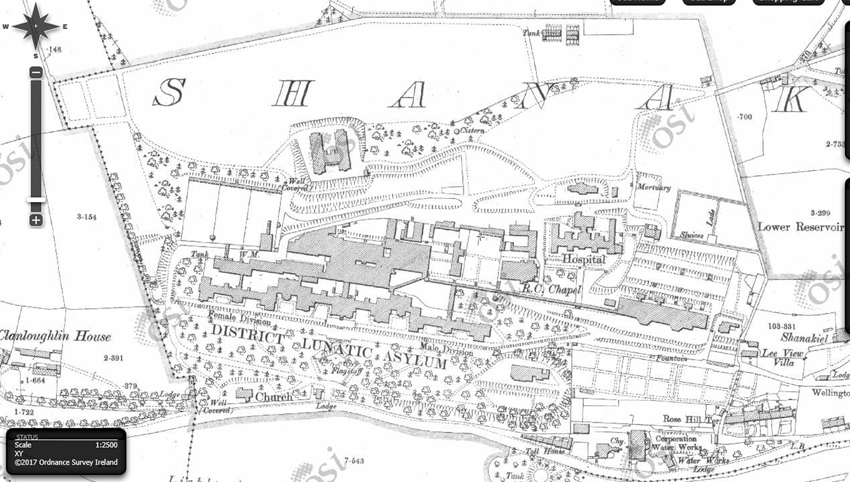

Etched into the northern skyline overlooking the Lee Fields is Ireland’s longest and one of its most atmospheric buildings. The old Cork Lunatic Asylum was built in Victorian times. The first asylum for what contemporary Cork society deemed ‘insane’ in Cork was founded under the Irish Gaol Act of 1787/8. The Cork Asylum was the second of its kind to be established in Ireland and was to be part of the South Infirmary on Blackrock Road. The Cork Asylum in the late 1840s lacked finance and space to develop a proper institution. A Committee of the Grand Jury of Cork County (leading landlords and magistrates) examined the existing asylum and began a verbal campaign for its replacement. In 1845, a Westminster Act was enacted to create a District Asylum in Cork for the City and County of Cork.

In April 1846, a Board of Governors of the Asylum at the South Infirmary purchased and commenced work at a new site in Shanakiel. The Board set up a competition of tender for an architectural design. Mr William Atkins was appointed, with Mr Alex Deane as builder. Work commenced in mid-1848.

The asylum was located on a commanding location on a steep hill, overlooking the River Lee. The building was three floors high and was divided into four distinct blocks. Three blocks were located at the front and were designed to contain the apartments for patients, along with the residences for the physicians, matron and other officials of the Asylum. The building materials were reddish sandstone rubble, obtained near the site, and grey limestone quarried from sites from the opposite site of the River Lee. Internal fittings such as fireplaces were said to be of marble supplied also from the southside of the city.

The fourth building block was located at the rear of the central block, and comprised the kitchen, laundry, workshops, bakehouse, boiler house and other rooms of an office nature. Heating was steam generated in a furnace house.

The new Asylum was named Eglinton Lunatic Asylum after the Earl of Eglington, and was opened in 1852. The principal types of people admitted which made up the highest number comprised housewives, labouring classes, servants, and unemployed. Forty-two forms of lunacy were identified from causes such as mental anxiety, grief, epilepsy, death, emigration to ‘religious insanity’, nervous depression, want of employment and desertion of husband or wife.

Plans for an extension to Eglington Asylum were put together in the 1870s. The aim was to accommodate over 1,300 patients. The three blocks were connected into a single building. In 1895, the Cork Asylum described as one of the most modern asylums in Western Europe. Conditions in the institution were quite good. Making up staff, there were 72 men and 56 women.

Lectures were given to staff by lecturers of mental illness at Queen’s University College Cork now University College Cork. A Church of Ireland chapel was completed in November 1885 with William Hill as architect. In 1898, a Roman Catholic Church was designed by Hill. In 1899, a new committee of management for the Asylum was established under the newly formed Cork County Council.

In 1926, the Asylum became known as Cork District Mental Hospital. In 1952, The Hospital’s name was changed to Our Lady’s Psychiatric Hospital. The complex closed in the late 1980s. In recent years, parts of the main grey building have now been redeveloped into apartment units.

Motorcycle Record Setting on the Straight Road, 1927:

In the early Irish Free State, tarmacem was introduced on Cork roads and the Straight Road in 1927 became a two-and-a-half-mile concrete road, which inspired the breaking of professional speed records of motorcycles.

The first major attempt to set a record was for a motor cycle speed meeting in 1929 at which speeds of a hundred miles per hour were attained. The first fastest motorcycle record was set unofficially by Glenn Curtiss in 1903. The first officially-sanctioned Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme record was not set until 1920. In mid-1930, Joseph Wright of Britain lost the motor cycle speed record to Jacob Ernst Henne (BMW) of Germany. Later that year, plans were made to retake the record. The 1930 Motorcycle Exhibition at Olympia, London was coming up in the second week of November 1930 and it was generally felt it would be good for business if a British machine could regain the record.

A few days before the London Motorcycle Exhibition in early November 1930, the Cork and District Motor Club directed the organising bodies of the new record attempt by British interests to the Carrigrohane Straight Road. The road’s fine surface brought Joseph S Wright, one of Great Britain’s foremost motor cycle racers came to Cork to attempt a new record. French officials arrived in Cork with special electric timing apparatus. Lieutenant-Colonel Crerar was director of the test. The first attempt was on 5 November 1930 but was postponed owing to continuous rain and greasy conditions on the road. The trial took place the following day.

Joseph Wright rode a 1,000 cc QEC Temple JAP-engine machine and regained the record by clocking up at just over 150 miles per hour. Appearing in a British Pathé movie, his clothing was strapped down to cut back on wind resistance. He even had tape put around his throat. He wore a streamlined motorcycle helmet. The bike was towed behind a car to get up to starting speed. the bike was built by Claude Temple who had himself already broken the speed record for motorcycles in about 1927.

Watch British Footage of Joseph Wright on Cork’s Carrigrohane Straight Road in 1927:

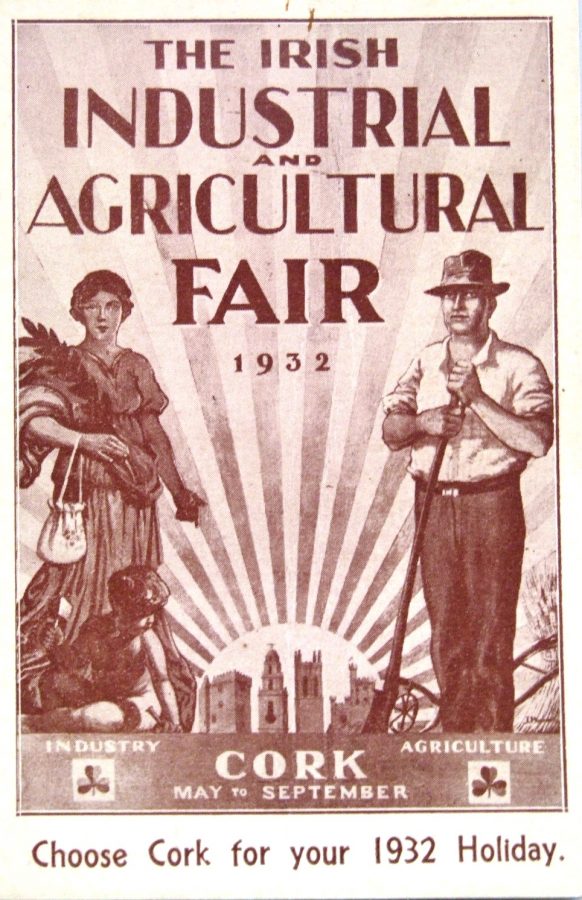

Cork’s Irish Industrial and Agricultural Fair, 1932:

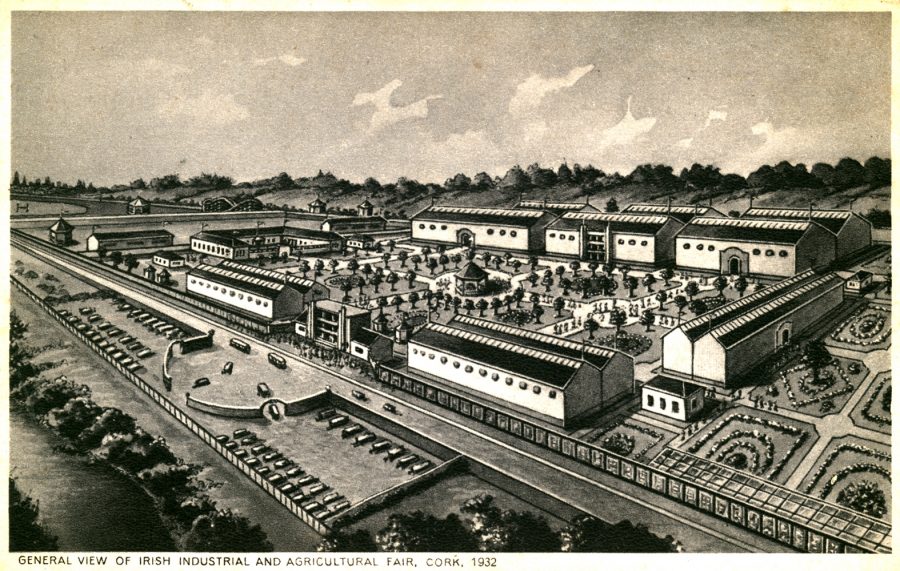

The ambitious Irish Industrial and Agricultural Fair was held in Cork in 1932 attempting to showcase Cork and Irish products in the early Irish Free State. Located in the southern section of the Lee Fields, south of the Straight Road, it is a lesser known fair in the history of the Exhibitions in Cork. It was the fourth attempt (1852, 1883, 1901/ 2, 1932) within eighty years to showcase Cork and its assets on a national and international stage.

Over eighty acres of land just off the Carrigrohane Straight were purchased from Mr T Corcoran, vice-chairman of the Cork County Council for this enormous fair. The architect responsible for the layout and design of an array of buildings was Mr Bartholomew O’Flynn, 60 South Mall, Cork.

The key buildings at the 1932 fair were listed as the ‘Industrial Hall’, ‘Palace of Industries’, ‘Hall of Commerce’, ‘Hall of Agriculture’, ‘Concert and Lecture Hall’, ‘Art Gallery’, ‘Tea Rooms’ and two large bars for which special licensing legislation was passed. Messrs. O’Shea Ltd., 41 South Mall, were the successful contractors for the building of the industrial halls, restaurants and car parks.

The ‘Hall of Agriculture’ main entrance and offices were constructed by Mr E Barrett, Knockeen, Douglas Road, Cork while the bars and lavatories were built by Messrs. Coughlan Bros. Sawmill Street. Mr Barrett was also responsible for the construction of an enquiry bureau on Cork’s St Patrick’s Street as well as the drainage system of the fair and a number of stalls and kiosks. Greenhouses and other structures in the agricultural and horticultural sections were erected by Messrs. Eustace and Co Ltd, 43 Leitrim Street. Messrs. Barry and Sons Ltd. of Water Street provided the timber for the buildings.

Over 50,000 people in the first two weeks visited in the first two weeks of the six-month run. Conscious of the fact that the fair was on the edge of the City, a new wide footpath was built along the Straight Road. The motor car visitor could park in an organised car park, which accommodated upwards of 3,000 cars under the supervision of the Fair authorities. Special exhibition buses, operated by the Irish Omnibus Company, ran from the city centre to and from the grounds. Special trains running from the western road terminus of the Muskerry Light Railway ran in the evenings to the site and back again.

In the years following the fair, a city dump or landfill was located on the site. This landfill remained in place for a number of decades before the Kinsale Road landfill came into being. That perhaps also added to the memory of the Irish Industrial and Agricultural Fair disappearing out of Cork’s public history. The site in recent years has become playing pitches.

Watch British Pathe Footage from 1932, “A Panoramic View of the Irish Industrial & Agricultural Fair at Cork”,

Lee Baths:

Photographs, a square hut of concrete in the Lee Fields and memories are all that remains of the infamous Lee Baths. The summer of 1934 coincided with the opening of Cork’s new municipal and open-air unheated swimming pool on the Lee Fields. Billed as one of the largest of its type in Ireland, it was officially opened on Wednesday afternoon, 20 June 1934 by Mr Hugo V Flinn TD, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Finance. There was a growing interest internationally in swimming and how the popularity of swimming pools was spreading. Oliver Merrington, in his work on the history of open air swimming pools, records that over 37 such pools opened in the UK in the 1930s. In Cork, the Eglington Street Baths (which were opened in 1901) could not accommodate the growing numbers of swimming enthusiasts.

The City Manager Philip Monahan with City Engineer, Stephen Farrington, set out to create an enterprise of considerable magnitude, which would have in it a large labour content for even the unskilled labourer, plus create a municipal project that would have social and economic value. In the wider context, Monahan was probably well aware of the growing interest internationally in swimming and how the popularity of swimming pools was spreading. Oliver Merrington, in his work on the history of open air swimming pools, records that over 37 such pools opened in the UK in the 1930s. In Cork, the Eglington Street Baths (which were opened in 1901) could not accommodate the growing numbers of swimming enthusiasts.

The inaugural gala at the Lee Baths took place after the official opening 20 June 1934. Witnessing the events was the Lord Mayor Sean French, Hugh V Flinn TD and other guests. Competitors compared the new site favourably with the Eglinton Street Baths and spectators commented on their spacious accommodation.

In the early years, women were not allowed to swim in the Lee Baths. The Cork Examiner’s record of the opening day highlights a letter of protest against the exclusion of ladies at the baths; seventy signatures were attached to it, the majority of which were women; others included that of a TD. They claimed that the Corporation was abusing its authority by prohibiting a large section of the population from bathing at the Lee Baths. Their letter gave the example of equality at the open air pools at Blackrock and Dalkey in Dublin Dun Laoghaire, Bangor, Portrush, Armagh, Warrenspoint and Newcastle. They asked for restrictions to be lifted at the Eglinton Street Baths and for the entire use of those baths during the summer months for women. Their requests were only met years later.

The site of the Lee Baths is now the Kingsley Hotel.

VIEW more nostalgia pictures here: Nostalgia: A look back at Cork’s famous Lee Baths (echolive.ie)

Grand Prix Car Racing, 1936-1938:

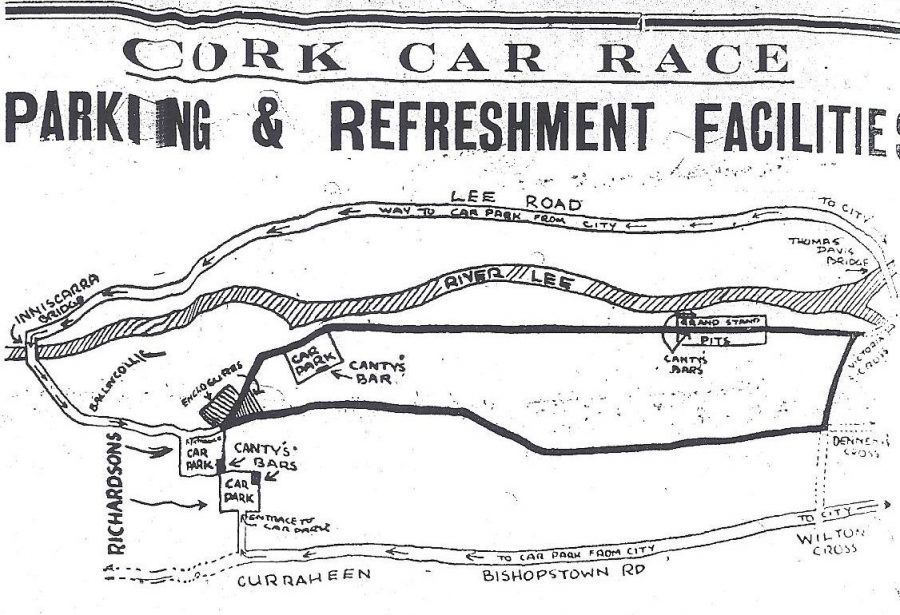

The years 1936-38 will be remembered as those which coincided with a sense of the international stitched into the Carrigrohane Straight Road. In the years 1929-1931 Phoenix Park, Dublin was the key venue for the Irish Grand Prix in motor car racing and was very well supported. Similarly, thousands of people came out on 5 August 1935 to see the first Grand Prix race in Limerick. Inspired by the Limerick races, the people of Cork were spurred to host a similar event in 1936 and subsequently in 1937 and 1938.

Being the first time, the venture was run in Cork, the race was not granted international status. An entry of twenty-seven was received. The most famous of the drivers was Austin Dobson, of Surrey, who piloted the Alfa-Romeo, in which the Italian ace Nuvolari won the German Gran Prix in July 1935. This car was reputed to be the fastest ever seen in Britain and Ireland, being capable of speeds up to 180 miles per hour, and in it Dobson was hopeful to set a new record. He already held the Phoenix Park record with 99.6 m.p.h. The majority of the English drivers who came for the Cork race arrived from Fishguard on the MV Innisfallen.

On Saturday 16 May 1936, the race day, the entire 6 ¼ miles of the course was crowed on both sides while all the vantage points held crowds six or seven deep. The distance of the track was 201 miles or 33 laps of the circuit. The starting time was 3.30pm and the estimated time of the race was two hours and twenty minutes. This is shown in the British Pathé short film of the event, In this there are various shots of cars starting the race in groups, multiple shots of the race and the crowds of people watching from walls of houses and front gardens along the race route.

The Irish Press in their press coverage (18 May 1936, p.12) noted that the course did not prove as fast as anticipated. Speeds of up to 130m.p.h were attained in the two mile Carrigrohane Straight Road but the back stretch, with its curving and undulating nature, was a severe test for cars and drivers. There was the Victoria Cross semi hairpin, the Poulavone hairpin, the wide right angled Dennehy’s Cross and the wide ‘s’ at the Gravel Pit bend, where the steep descent to a left hand turn called for as the Irish Press noted “extreme caution or dare devilry”. Reginald Ellis Tongue of Manchester won the race in an English Racing Automobile or ERA. at an average speed of 85.53 mph. in 2 hours, 12 minutes and 22 seconds.

Such was the success of the 1936 that two further Grand Prix took place on the Straight Road and environs in 1937 and 1938.

Watch British Pathe film footage from 1936, Cork Motor Race – British Pathé (britishpathe.com)

Cork County Hall:

Cork County Hall for many years had the title of the tallest building in Ireland, to be surpassed by the Elysian Tower on Eglinton Street, just east of Cork City Centre. Since 1899, Cork County Council met at Cork City Courthouse and various departments of the Council were scattered throughout the county. A site was purchased prior to World War II but with the rapid post war expansion of the local government services it was decided that the site, located in the city centre was entirely inadequate.

In 1953, the idea of a central headquarters for the Council’s officers was first mooted by Mr Joseph F Wrenne, first County Manager. At the time, the times and costs were not considered. Mr Owen Callanan succeeded Mr Wrenne and he attained the council’s approval in principle to one big roof for all in 1954.

The original proposed building was to be ten storeys, 116 feet tall, 187 feet long and 42 feet high. Its long frontage was to face the Carrigrohane Road and the cost of £137,000. The final plans different to what was originally proposed. The County Hall as finally designed by the then County Cork Architect, Patrick McSweeney, cost half a million pounds, was built of seventeen storeys, 211 feet tall, 131 feet long and 46 feet wide, with the main entrance facing the city.

Cork County Council acquired the site from John A. Wood. Previously, the greater part of the land was the headquarter grounds of the Munster Football Association. In 1964, the tender for the sum of £479,508 was accepted from Cork’s largest firm of building contractors, Messrs P J Hegarty and Sons, Leitrim Street, was accepted for the construction of the seventeen storey skyscraper.

A design feature also made it possible to build higher than ever before without the necessity for scaffolding, which would have cost circa £20,000. The cost cutter was to extend the floors beyond the outer walls – so that each successful floor became the work platform for the laying of the next floor on its supporting 28 columns and beams. The beams were 14 inches thick and the floors were comprised of 6 inches of reinforced concrete.

The building rose at the rate of one floor every three weeks until it reached the 16th floor. Instead of finishing off the upper storeys, a decision was made, arising out of the expectation of the advent of the worst of winter weather, to consolidate the lower floors installing curtain walling, glazing internal partitioned walls and giving the building a chance to dry out.

Cork County Hall was officially opened on 16 April 1968

WATCH: Cork County Hall celebrates 50 years of service to people of Cork:

County Hall Sculptures:

At the base of County Hall are two bronze figures entitled Two Working Men. Sculpted by prominent Irish sculptor, Óisín O’Kelly, the bronze figures were a commission by the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union. They were designed to stand at the base of Liberty Hall in Dublin, the union’s skyscraper headquarters. However the figures could not be erected because Dublin Corporation refused planning permission for them.

Through the generosity of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union the figures were acquired on loan by the then Cork Sculpture Park Committee. In 1969 the bronze figures came to Cork through the good offices of the sculpture committee and were put on exhibition in Fitzgerald’s Park.

When the time came to pack the figures up and send them back to Dublin the committee felt that it was a pity to see such beautiful artistic work going away for possible storage. It was at this stage that the Cork branch of the the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union stepped in and through their influence the figures were retained in Cork on loan for exhibition at County Hall. In February 1971, Mr Patrick MacSweeney, the then County Architect, had them placed in a most appropriate position in front of the 211 feet high Cork County Hall – and there they remain.

Cork Coco Cola Bottling Plant:

The opening of the Coco Cola bottling plant in Cork adjacent the road on the 9 May 1952 was a success story for the Irish government who sought out such companies. It was also a success for the directors of the Munster Bottlers Limited that had only been founded 11 months previously to the opening. Company chairman Mr. P. Fitzgerald from Rushbrooke greeted the guests at the opening.

With a legacy going back 125 years, the beverage Coco Cola was invented in 1886 in Atlanta, USA and quickly blossomed into one of America’s most important exports abroad. In 1900 there were two bottlers of Coca Cola; by 1920, there were about 1,000. In 1941, when America entered World War II, thousands of men and women were sent overseas. Coca Cola rallied behind them when its CompanyPresident Robert Woodruff ordered that every “man in uniform get a bottle of Coca Cola from five cents wherever he is and whatever it costs the company”.

In 1943, General Dwight Eisenhower sent an urgent cablegram to Coca-Cola, requesting shipment of materials for 10 bottling plants. During the war, many people tasted their first Coca Cola, which laid the foundations for Coca-Cola to do business overseas. Hence by the mid 1940s until 1960, the number of countries with bottling operations nearly doubled. Post war America was deemed alive with optimism and prosperity. Coca-Cola was part of a fun carefree American lifestyle. Ireland was part of the expansion of the bottling works. The case of the country was also strengthened by Jim Farley, Chairman of Coca Cola.

In an article in the Irish Press in September 1968 it outlined that his Jim Farley’s grandfather came from Co. Meath. Jim was described a “legend in U.S. Politics” and was a former member of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s cabinet. Farley started in public life as town clerk of an up-state New York town and from there became chairman of the Democratic Party National Committee. He helped start the Roosevelt campaign in 1932 and managed his presidential campaign, after which Farley became Roosevelt’s first Postmaster General. He had been associated with the Coca Cola company since 1940.

At the Cork plant, all the necessary commodities that went into the manufacture of the drink were native products with the sole exception of the concentrated syrup, which was imported from England. The Coca Cola Export Corporation was the largest single consumer of sugar in the world. The creation of bottles, crates and the use of vehicles created business for local industries. In addition, starting off the Cork Plant had a dozen staff.

The Cork Examiner on the day of the opening (9 May 1952) carried a feature on the workings of the plant: “The factory itself is very modern and it was designed by Mr. H. Fitzgerald-Smith to conform with the high standards required by up-to-date bottling factories. A single storey building…in the factory proper there are large windows, which will allow the maximum of light necessary for the work on complicated machines….At the eastern end there is an overhead syrup room. From which the main ingredients flows to the factory below to be processed.”

In view of the fact that the Coca-Cola Company insisted on one quality of water it was found necessary to install a water treating plant. Another unique feature was a washing machine, which was capable of washing and treating 30 bottles per minute. The regulations of the Coca-Cola Company required that every bottle had to be thoroughly sterilised before it is passed for use. Temperature, too, had to be kept at a certain degree, and in this connection a special refrigeration plant was in operation.

The bottling machine was described as a “mechanical marvel, which performs several operations. As the bottles pass along a conveyer they are filled, crowned and then go through a very minute inspection before being finally adjudged as suitable for dispatch to the retailer.”

The firm had a special department for training salesmen and these men when trained were to act as driver salesmen throughout the Munster counties. The crown corks were made in Cobh. The bottles were supplied from Dublin as well as wooden containers. A fleet of ford trucks were used. The factory was erected by Daniel T. O’Connor and Sons. By 1963, there were four bottling plants in Ireland of Coca Cola and these were part of a wider family 650 bottling plants in 118 countries.

Saurian Sculpture Piece:

Taking its home at the Lee Fields in August 1985, Jim Buckley’s dragon like sculpture called ‘Saurian’ is approximately 15 feet tall, 30 feet long.

Jim’s monster shaped piece was only one of six sculptures made outdoors at the ANCO headquarters at Bishopstown in Cork, and all six works were placed in and around Cork city before the end of 1985. They were part of the Cork 800 Sculpture Symposium.

Five of the six sculptors were Cork based, Jim Buckley, John Burke, Eilis O’Connell, Patrick O’Sullivan and Vivienne Roche, while the sixth, Hironon Katagiri came from Japan.

Lark by the Lee, 1985 at the Lee Fields, Cork:

U2 surprised Cork with an unannounced performance at the annual August music concert Lark by the Lee. U2 flying high with their ‘Unforgettable Fire’ tour play to an astonished but delighted audience of around 7,000 people by the River Lee in Cork. The band were introduced to the unsuspecting audience as,

“There’s an up and coming band coming on the stage now and playing for you, they’re called…U2”.

U2 played a nine song set in total. In this footage shot for RTÉ News the band are playing ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’. A number of fans close to the stage pass out during the performance and have to be taken to a nearby hospital.

The free open air concert was organised by RTÉ Radio 2 and Cork Local Radio.

An RTÉ News report broadcast on 25 August 1985,

RTÉ Archives | Entertainment | U2 Appear At Lark By The Lee (rte.ie)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnnUodmraeM

Ends.