In September 1690, King William despatched the Earl of Marlborough, and a large contingent of men to regain control of Cork. On Monday, 22 September 1690, Marlborough arrived in Cork Harbour with over eighty ships and approximately five thousand men. A landing was opposed at Passage by Irish rebels, who possessed a battery of seven or eight cannons. However, they were soon overrun by several armed boats sent ashore to deal with this opposition.

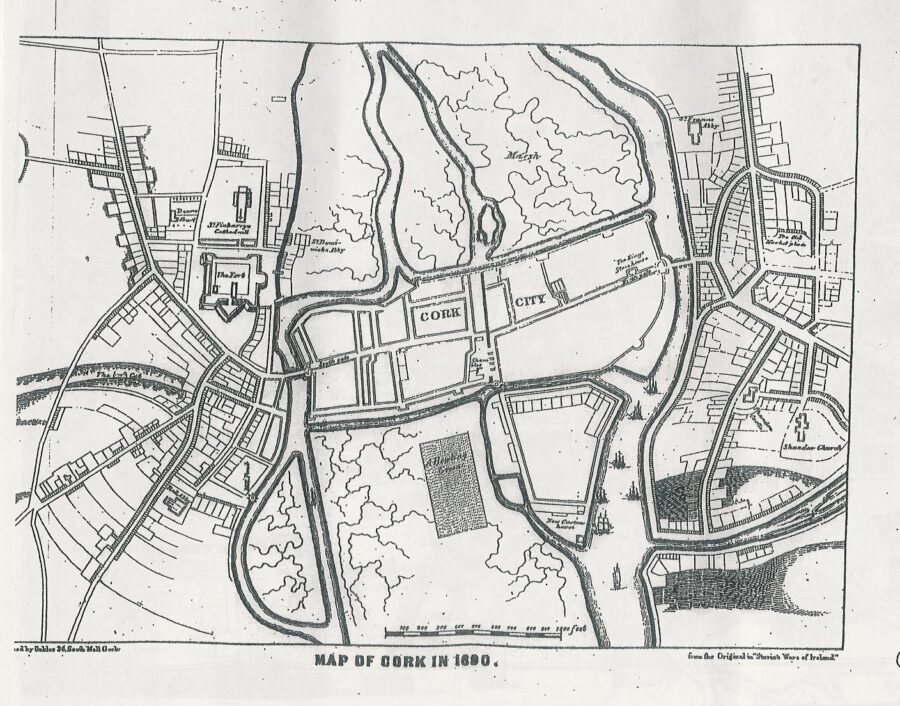

The next day, Marlboroughs’ troops disembarked at Passage. A regiment of about 800 men marched through Douglas and camped in the area of the Lough. A small contingent of Irish rebels attempted to block their passage but they were fired upon and killed. Marlborough decided that he could exploit the main defensive disadvantage of the walled area: its low-lying position overlooked by hills. Control of the hills would mean control of the walled town.

After advancing on the southern environs of the town, the English regiment set their sights on Cat Barracks, which was adjacent to the southern road leading to South Gate Drawbridge. This was a small barracks, constructed in 1685 by Thomas Philips, used as a storage depot for the firearms of nearby Elizabeth Fort. The rebels retreated into the town as the English advanced, setting fire to the southern suburbs as they did so – the area now occupied by Douglas Street, Cove Street and Barrack Street.

Marlborough dispatched General Ginkel and General Scravenmoer to secure the northern liberties of the town with the assistance of a cavalry comprising 1,200 men. An infantry consisting of Dutch soldiers under the command of a Major-General Tettau was also dispatched. At this point, Scravenmoer sent a message to the leader of the rebels, known as Colonel Mc Ellicutt, asking him not to burn any part of the city. The governor replied that he was not afraid of the advancing army and would burn what he saw fit.

In the afternoon of 23 September 1690, Tettau ordered the cannons to be transferred from their camp in the northern liberties to Fair Hill, just to the west of present-day Commons Road. This was an attempt to mount an assault on Shandon Castle. The rebels again set fire to the suburbs, this time around Shandon, and retreated within the safety of the town walls. Even an old church called Shandon was burned along with the Franciscan Friary on the North Mall.

On Thursday, 25 September, Col. Hale and two hundred members of his regiment advanced on Cat Barracks and, finding it deserted, immediately took possession of it. At this time the focus of the attack moved towards Elizabeth Fort, the stronghold of the Jacobite side. Bombardment of South Gate Bridge and the eastern wall also began. During the night, the attackers moved closer to the fort and hid themselves in ditches and laneways.

On Friday, 26 September, constant bombardment of Elizabeth Fort resulted in the collapse of the wall above its gate and part of the adjacent bastion. Shells from a mortar were fired into the city, killing two or three people. Meanwhile, on the northside, the Duke of Wurtemberg arrived at Scravemoer’s camp with a large force. Together, they made an advance on Shandon Castle, which they found also deserted. Scravemoer sent all his cavalry to join Marlborough on the southside, just by the site of present-day St. FinBarre’s Cathedral.

On Saturday, 27 September, the bombardment of the city escalated. The cannons concentrated on breaching the eastern wall, a point now marked by the City Library on the Grand Parade. Scravemoer decided to use the spire of St. FinBarre’s Cathedral as a vantage point from which to fire into the town. Lieutenant Horatio Townsend was chosen along with two files of men to mount a gun on top of the spire. The governor of Elizabeth Fort was killed by a musket shot from the spire. In retaliation, the Jacobite soldiers aimed two guns at the steeple and shook it immensely. Townshend is reputed to have refused to yield, ordering the access ladder to be removed from the base of the cathedral. Eventually, however, he was forced to retreat.

After a few more days of sustained attack, the rebels within the walled town surrendered. There were several reasons for this. Large portions of the town walls, North and South Main Streets, laneways and houses had been destroyed. The leader of the rebels, Mac Elligott, noticed that there were significant breaches in the wall and that the enemy had dug large ditches on adjacent marshy islands in an attempt to get closer to the town walls. In addition, Mac Elligott’s side was nearly out of ammunition. McEllicutt’s terms of surrender included the plea not to burn the suburbs surrounding the walled town. His request was denied, but he was obliged to sign the conditions of the Duke of Marlborough.

The key figures on the rebel side were summarily executed, along with several members of their families, and the suburbs were burned and destroyed. Elizabeth Fort was surrendered within one hour of the signing of the agreement, as stipulated, and the town gates were surrendered the following Monday morning at eight o’clock. All arms and ammunition were left in a secure place for the English to collect.

The principal rebel leaders were transported to the Tower of London. Many of the Jacobite soldiers were imprisoned in Clonmel, while many more were sent to jails in London. Col. John Hales replaced MacElligott as governor and was presented with the freedom of the town in a silver box. The Duke of Marlborough also received the freedom of the town from William of Orange.

Today, two interesting remnants of the Siege of Cork can be seen in the city. On the corner of Grand Parade and Tuckey Street, embedded into the pavement, is a canon that was reputedly used in the battle; it is thought that it was later used as a mooring post for a quayside in the 1700s.

The second item is a canon ball fired from Elizabeth Fort at the tower of St FinBarre’s Cathedral. During the rebuilding of the cathedral in 1735-1738, this twenty-four-pound cannon ball was found embedded in the spire, about ten metres from the ground. It is on display in the ambulatory of the present cathedral. The siege proved to be a major catalyst in initiating change in the physical and social landscape of the city.

Read more and Explore more: 4a. Cork, A Venice of North West Europe | Cork Heritage