Introduction:

Many stories can be read on The Great Famine in the multiple published works in our local history libraries. In these huge questions on this era are raised on how the Famine transformed localities and ultimately affected society across the spectrum of the Irish landscape.

In the present day history books in school, the reader is drawn to very traumatic terms. The recurring visions comprise words such as potatoes blackened, rotten, wasted, human destruction, appalling, tragic, stretched bodies, trauma, devastation, sorrow, harrowing, holocaust-like, loss, exile, suffering, eviction, poverty, starvation, perishing, disease, lethal fevers.

Basic Stats:

In truth, The Great Famine, of the late 1840s, was the most tragic event in modern Irish history. Prior to the Famine’s commencement, the Irish population had more than trebled in the century before it, from approximately 2.5 million people in the year 1750 to about 8.5 million in the year 1845.

An increase in population growth put huge strain on the country’s land and food resources, and placed a dangerous dependency on a single food source, that of potatoes.

In September 1845, the potato blight emerged in Ireland for the first time, and destroyed about one-third of the country’s main crop of potatoes. In the following year, blight returned and affected almost the complete potato harvest.

Autumn 1845, The Crop Fails:

By the Autumn of 1845, the poverty situation in Cork City was to escalate to a new level. At this time, reports of potato plight could be heard in many parts of the country and were soon found in crops near the city. As both the majority of the both wealthy and poor depended largely on this crop as a staple diet, large scale worry began to set in.

On a national scale, it was immediately planned to keep other crops such as corn, oats and barley in the country. However, by January 1846, the supply of such crops has decreased to less than half the previous year’s figure and prices had vastly increased. This created social upheaval in the country and led to the growth of relief committees.

April 1846, Establishing the Cork Relief Committee, :

In the case of Cork City, the Cork Relief Committee was officially established in April 1846 but was operating unofficially during previous weeks. This committee bought sacks of Indian meal from the government store and sold them at cheaper prices to the public. Initially, they had three selling outlets, York Street on the northside, Little Market Street in the central area and Barrack Street on the south side.

Such was the demand for food that in one particular day on 28 March, the available meal was sold within a few hours. Meal and wheat were immediately re-ordered from Liverpool and three new selling outlets were opened by 11 April. The Cork Relief Committee itself met twice a week, and by the end of April, £3,000 had been subscribed to them by the public.

Late Spring1846, Public Meetings and Employment Schemes:

As well as their meetings, there were also public meetings where employment schemes and food distribution were discussed. Most of the discussion though involved criticising the government and the delays in sending on food and providing work.

Early Summer 1846, Forming Parochial Sub Committees:

Existing food depots were unable to keep pace with the demand for relief and the food that was given out was inadequate for the needs of a family. In addition, the more impoverished who would have gone begging in country areas remained in the city. Consequently, parochial sub-committees were established in association with the clergy and charitable groups such as an Infant Society of St. Vincent de Paul.

However, these city parish committees began to seek higher allocations to cater for higher demands within their parish. The price of food itself at depots was set, six pence for seven pounds of meal and three-quarters pence for one pound of bread. It is noted though that Indian meal tended to make children sick. The bread itself was baked from a mixture of meal and flour.

Early Autumn, 1846, The Harvest Fails Again:

By the end of the summer of 1846, there was optimism that the harvest was going to be better and discussion began on how to dispand relief schemes. Disaster occurred though as the harvest failed. This coupled with problems in the escalating price of Indian meal and delays in documentation in work schemes brought the social crisis into a worse situation.

Reports of deprivation in County areas became more alarming each day and country people continued to pour into the city to inhabit the lanes and alleys. This in turn placed increased pressure on the limited resources available in the city.

WATCH a short RTE promotional film on The story of the Irish Famine:

Autumn 1846, Further Problems:

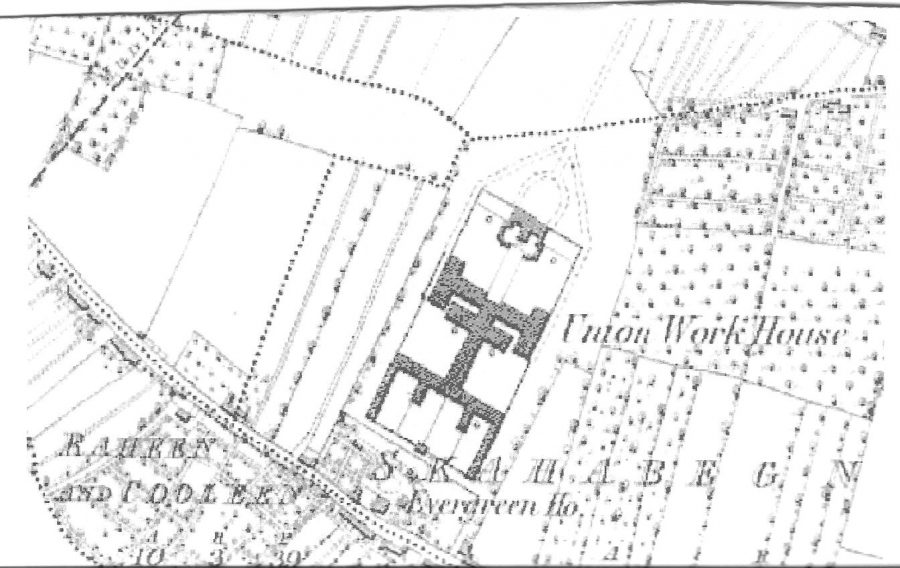

However, as the autumn of 1846 progressed, problems were to only grow. Prices of Indian corn increased considerably. Merchants began to price fix and as a result, the relief committee had great difficulty in keeping ahead of the demand for food. The Douglas Road Workhouse had 3,000 inmates due mainly to the desperate employment situation. In addition, a large number of non-residents were provided with a breakfast.

In early September 1846, there were 4,256 non-residents. By the start of October, this figure had grown to 11,633 non-residents. The Poor Law Commissioners who argued it was an insult to the labouring classes disapproved this whole practice.

October 1846, Overcrowding at the Cork Union Workhouse:

By mid-October 1846, the number of Douglas Road workhouse inmates had climbed to over 3,500. it was opened in 1841 for 2,000 people Five hundred were admitted in one week at the start of November. Overcrowding was a major problem. Four people were placed in one bed.

The Workhouse Guardians also rented additional premises, which in total brought the population of the workhouse up to 4250 by November 1846. The full capacity was just 100 inmates more, 4350. Of course by December, overcrowding was a problem again. It is recorded by mid-December that there were 4,585 inmates. In the workhouse, to help out costs, soup was substituted for other food such as milk, oven purchased, bakery manned by inmates.

There was also an increase in the rise in deaths in the workhouse. Between 17 October and 2 January 1847, there was on average four to five deaths, per week.

1846, Carr’s Hill Graveyard,

As St Joseph’s graveyard could not cope with increase, Fr. Mathew suggested to the guardians that a new burial ground be acquired. As a result, land was attained from George Carr, a workhouse official on the road between Douglas and Carrigaline.

View Kieran’s All Saint’s Cemetery film here:

1846, Works in the City:

In addition, employment for the destitute was scarce. The relief committee had 700 men on their records seeking work. Consequently, work had to created. The Harbour Board decided to employ 100 men who were to work creating new roads, in the city’s surrounding countryside and also in stone-breaking at the new park (now Pairc Ui Chaoimh area). Since the situation was so bad that the board employed several hundred extra hands.

The repair of the Navigation Wall (now The Marina) gave employment to 1,000 people who were employed by year’s end and on quay works on the northside of the river. Other relief works instigated included a new military prison in the Cork Barracks. Destitute people were also employed in building works at Cork’s Lunatic Asylum, Queen’s college (now UCC).

New railway works were also contemplated along with new city markets. 400 labourers were planned to be used on the building of a new network of railways in the northern suburbs of the city under the direction of the new Great Southern and Western Railway (see future articles).

November 1846, Poverty on the City’s Streets:

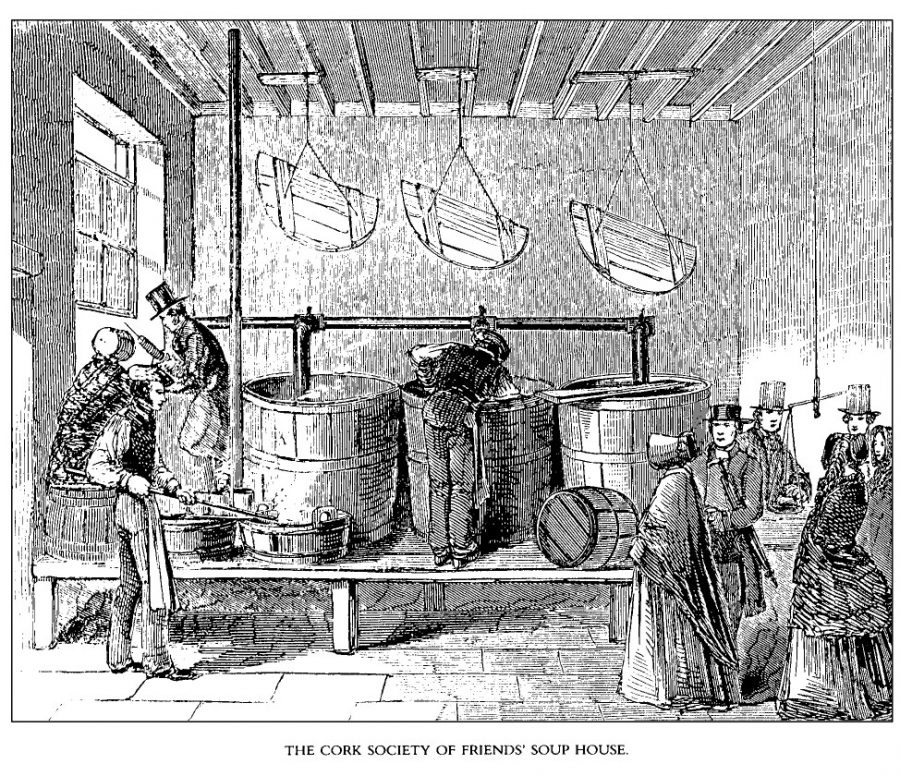

In November 1846, city officials recorded 5,000 half starved impoverished people begging on the streets. As the winter progressed, discussion began on establishing soup kitchens. The Society of Friends had applied for permission to use part of the North Main Street market for such a project. The preference by the Cork Relief Committee was that soup Kitchens should be run by local parish committees.

December 1846, More Soup Depots:

By mid December, the Cork Relief Committee had established the Southern and Central Soup Depot Committee who had set up two soup outlets. By the end of December, five soup depots were operating. These included Shandon (capacity of 400 gallons), Blackpool (200 gallons), Harpur’s Lane (200 gallons), Adelaide Street (200 gallons). Shandon Soup comprised of boiled oatmeal, rice, coarse beef, turnips, chilli pods (peppers), leeks and celery.

Winter 1846, Starvation in the City:

This was a period of extreme food shortages, which caused escalating food prices, food stealing and food riots.

The resident population of Cork city was amplified by starving people from the county and further afield who swarmed into the city in search of assistance.

The city’s limited charitable and relief resource broke.

Cork county’s workhouses filled beyond their capacity.

Fever and dysentery raged epidemically, intensified by the effects of starvation, and these diseases cut impoverished areas.

The British government’s reaction to the catastrophe was utterly inadequate.

Spring 1847, Poverty Continues:

In early 1847, more and more country paupers appear in city’s streets and laneways. During this time, it was argued that 30,000 beggars were in the city seeking relief. However, food from relief depots was beyond their financial means. Shelter was provided by the Relief committee who constructed night sheds. They roofed sections of the markets in the city and separate markets used to shelter the male and female poor. The City’s police also gave shelter. In the first week of March, 200 were given shelter at four of the citys’ stations.

April 1847, Captain Robert Bennet Forbes & USS Jamestown:

Captain Robert Bennet Forbes, commander of USS Jamestown, which had arrived in Cork harbour from Boston on 12 April 1847 with some 800 tons of relief provisions for distribution in Cork, visited the city in the company of Fr Theobald Mathew, and was shocked by the scenes he witnessed in Cork’s side streets and back lanes.

He recorded:

“I saw enough in five minutes to horrify me’, ‘hovels crowded with the sick and dying, without floors, without furniture, and with patches of dirty straw covered with still dirtier shreds and patches of humanity; some called for water to Father Mathew, and others for a dying blessing”.

1847, The Workhouse:

Regarding the workhouse, at the start of January 1847, 4,000 inmates were estimated as inhabiting the buildings of the work house. There was a concern though by house physicians that overcrowding was aiding the help of the spread of fever. As a result of overcrowding, there were limits on admissions.

Aerial view of remains of Cork Union Workhouse, now within St Finbarr’s Hospital, Douglas Road, Cork, present day (picture: Google Earth)

October 1847, Relief Depots Established:

By the end of October 1847, there were ten relief depots; the top of Mallow Lane; Shandon Street; Lower Blackpool at the Watercourse; Globe Lane; Fishamble lane; Barrack Street; St. Lukes Cross; Anglesea Bridge and the old Cat Barracks. Each day, 25,000 people supplied with yellow and white meal.

1848, The Crisis Decreases:

In 1848, the return of the crop brought a sense of hope to every citizen in the city. As the city straddled the middle of the nineteenth century, problems were still inherent, particularly the slums. In the early 1850s, there were some Local Improvements Acts, in particular the building of a number of new streets and new houses.

1851, The Middle of a Century:

A survey of the city’s lodgings along with the census of Ireland, both completed in 1851 reveal deplorable conditions. Both detail overcrowded parishes. The census of 1851 revealed that seventy per cent of families in Cork were living in slum conditions. This percentage remained the same for decades to come. The three most overcrowded parishes included Holy Trinity, St. Paul’s and St. Peters. On average, ten people lived in each house in these areas.

1845-1861, Emigration Grows:

Forced emigration was evident. Some 2 million people emigrated from Ireland in the decade 1845-1855. With 250,000 departing Cork Harbour. Death and emigration reduced the population of County Cork from 854,118 to 649,903, or by almost 24 percent.

Between the census of 1841 and that of 1851, although the city’s population increased from 80,720 to 85,745 as a result of the influx of rural migrants.

The demographic impact was dramatic and were to linger for the remainder of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century.

WATCH: A re-creation of “Mud Hovel” at UCC:

WATCH: Images from the book, Atlas of the Great Irish Famine

Irish Famine Video – Atlas of the Great Irish Famine- book – YouTube

In Truth:

The memory of the Great Famine is both sensitive and compelling. There are many threads of its history to interweave – the political, economic and social framework of Ireland at that time plus the on the ground reality of life in the early 1800s – family, cultural contexts, individual portraits.

There is much to remember, reflect upon and commemorate and much, which has shaped Irish society in the present day.

Read more and Explore more, 5c. On Track, Cork & its Railway Heritage | Cork Heritage