By the early 1170s the Anglo-Normans had taken control of large tracts of land from Waterford to Dublin. In 1172 they turned their attention to Cork. Two Anglo-Norman lords, Milo de Cogan and Robert Fitzstephen, were despatched to Corcach Mór na Mumhan with a small land force to confront and dispossess the Vikings and chief of the McCarthys, Dermod McCarthy, of his lands in counties Cork and Kerry.

Once the McCarthys had been defeated, Fitstephen and De Cogan’s began the transformation of the settlement into an Anglo-Norman town. It was to become one of fifty-six early Anglo-Norman walled towns established in Ireland, some re-founded on adapted and extended Viking settlements sites.

Initially, the Anglo-Normans noted that the Danish settlement on the marshy island was “fortified” and had a gate (“porta”) leading into it. The nature of the fortification, whether it was stone or timber, was not recorded. Incorporating elements of the old settlement, the newcomers instigated many fundamental changes to the town.

The name of the town was shortened to Corke. The renaming was significant as it was the first instance of the anglicising of local Gaelic culture. In addition, in the late 1100s, Henry II chose Bristol as the model to be followed in developing manorial towns in Ireland, especially in issues such as liberties, privileges and immunities.

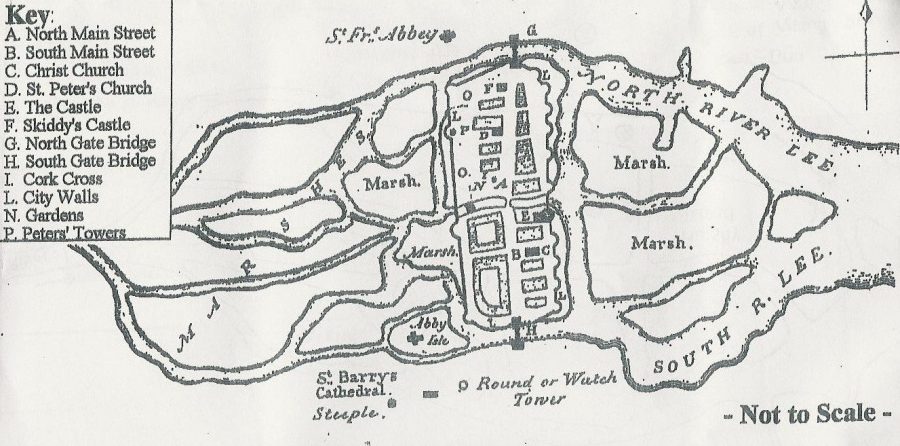

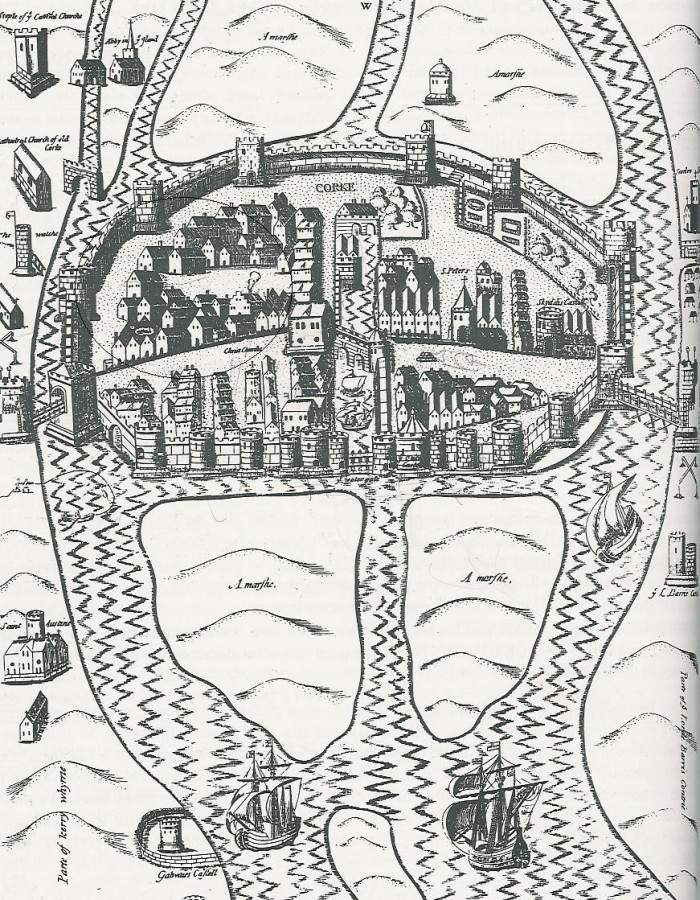

Between the 1170s and 1300s, a stone wall, on average eight metres high, became the new perimeter fence for the old Viking settlement area on the island, which was accessible via a new drawbridge built on the site of the Viking bridge, Droichet. Beyond this wall, a suburb called Dungarvan (now the area of North Main Street) was established on a nearby island.

By 1317 the full circuit, which included the extension of the wall around Dungarvan, was complete. Thus the redevelopment of the town walls created one single walled settlement (16 acres in extent) instead of a walled island with an unfortified island settlement and Dungarvan outside it. Within the town a channel of water was left between the old walled settlement and the newly encompassed area of Dungarvan, with access between the two provided by an arched stone bridge called Middle Bridge. A millrace dominated the western half of this channel, while the remaining eastern was the town’s central dock.

On the wall at regular intervals were mural towers, which projected out and were used as lookout towers by the town’s garrison of soldiers. The walled town extended from South Gate Bridge to North Gate Bridge and was bisected by long spinal main streets, North and South Main Streets. These were the primary routeways and although narrower than the current streets, would have followed an identical plan. They would also have been the main market areas.

The town was now well defended and all those seeking to gain entry had to use one of the three designated entrances: one of the two well-fortified drawbridges with associated towers or the eastern portcullis gate. The first drawbridge, allowing access from the southern valleyside, was South Gate Drawbridge, while entry from the northern valleyside was via North Gate Drawbridge.

From 1300 to 1690 these were the only two bridges spanning the River Lee. There are still bridges on their sites today and they still possess the names North and South Gate Bridge. The present South Gate Bridge dates to 1713 while the present North Gate Bridge dates to 1961.

The third entrance overlooked the eastern marshes and was located at the present-day intersection of Castle Street and Grand Parade. Known as Watergate, it comprised a large portcullis gate that opened to allow ships into an small, unnamed quay located within the town. On either side of this gate, two large mural towers, known as King’s Castle and Queen’s Castle, controlled its mechanics.

The Anglo-Normans consolidated this port by establishing new export destinations and by the end of the seventeenth century, the walled town of Cork was exporting to other European ports such as to Bordeaux, in France, and to a large range of English Ports such as Bristol, Chichester, Minehead, Southampton and Portsmouth. Trading contacts were also made across the Atlantic Ocean to eastern North American ports such as Carolina and those in the Carribean, trading goods such as beef and butter. In addition, the sheltered nature of the mature river valley and Cork harbour has provided a safe berth for ships right through the ages.

Great digital map by ‘Sketch-Up Expert’ showing former area of the walled town of Cork:

Read more and Explore more: 2b. Life in Medieval Cork | Cork Heritage