From a waterway, to the boundary of a town wall to being a canal and broad street, Cork’s Grand Parade has a myriad of historical stories attached to it.

Below is a brief historical walking trail, which covers some of the topics on my physical walking tour. The information is abstracted from various articles from my Our City, Our Town column in the Cork Independent, 1999-present day, Cork Independent Our City, Our Town Articles | Cork Heritage

The King’s Castle:

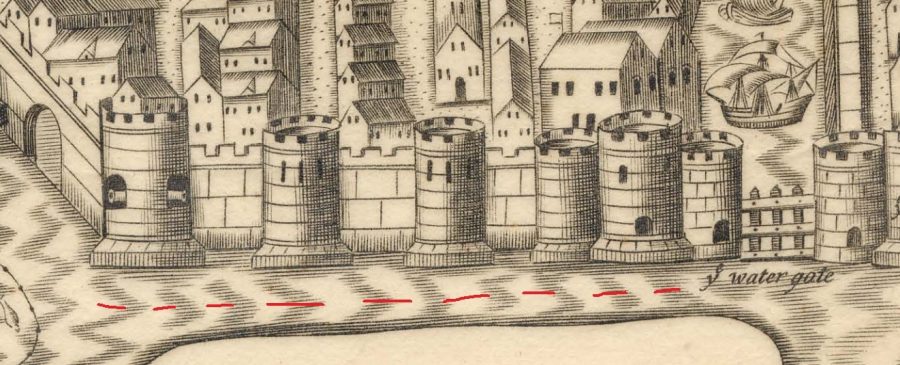

The Watergate of the Walled Town of Cork was situated at the junction of the present Castle Street and the Grand Parade.

The Castle on Watergate’s northern side – the site of Cornmarket Street -was known as the Queen’s Castle.

On the southern side of Watergate stood the King’s Castle, the most important building in the ancient city. It is mentioned in the old charters under various titles — The Castle of Cork, The King’s Castle, The King’s Own Castle, and The King’s Old Castle.

A charter in the reign of Charles I, dated 7 April 1632 states: “The King’s Old Castle, the County Gaol, then called the lower room of the said Castle, with the common place of execution to continue- in the county at large. The Corporation covenants with his Majesty to build the same Session House and keep it for ever in repair.”

This Session House was built in 1680, to which the Corporation contributed £100 It is described as a large, commodious structure, with adjacent grand and jury rooms.

The Courthouse built in 1680 was rebuilt and renamed King’s Old Castle in 1806. It consisted of a handsome pediment of Portland stone, supported by fluted Doric columns, resting on a rustic basement.

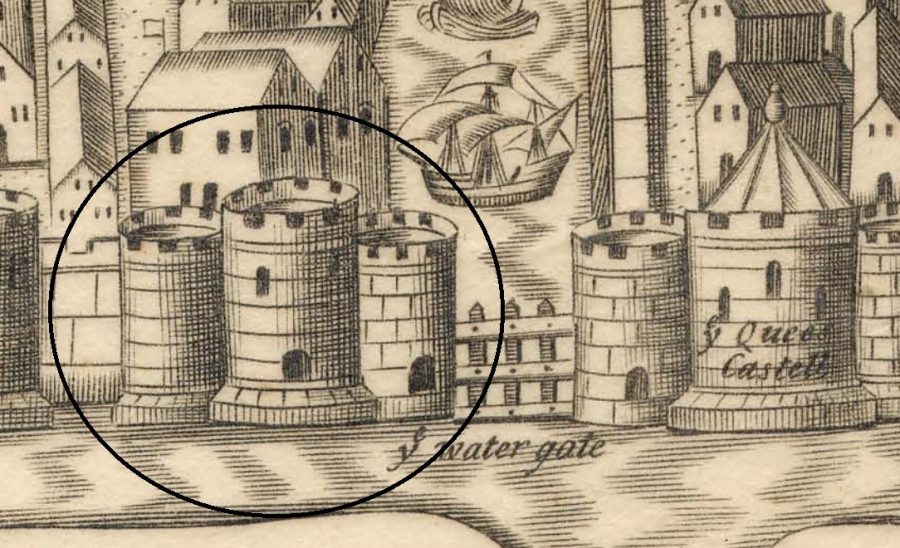

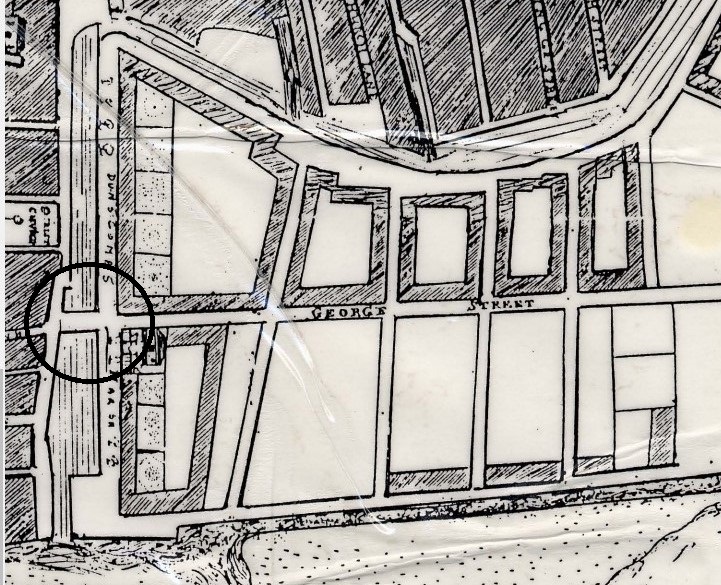

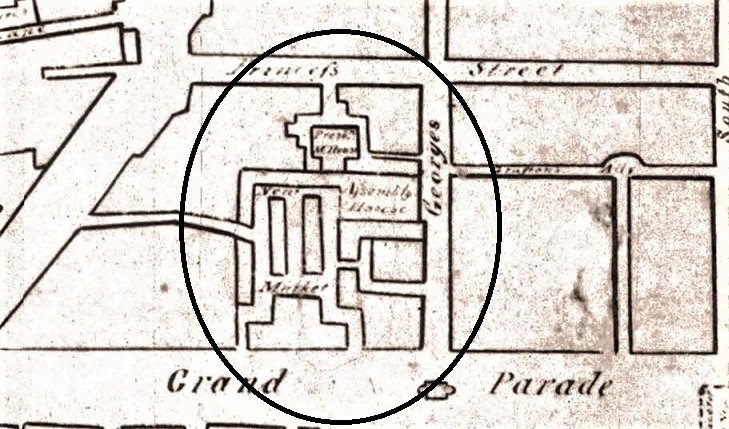

Sketch of Watergate and King’s Castle (circled), centre right, from George Carew’s Map of Cork c.1600 (source: Cork City Library)

Creating Queen’s Old Castle:

After the erection of the new Courthouse in the 1830s on Washington Street, these premises being no longer required by the county, an Act of Parliament was obtained for their surrender on valuation.

The building on passing into the possession of William Fitzgibbon was renamed The Queen’s Old Castle, a compliment to Queen Victoria who was then reigning.

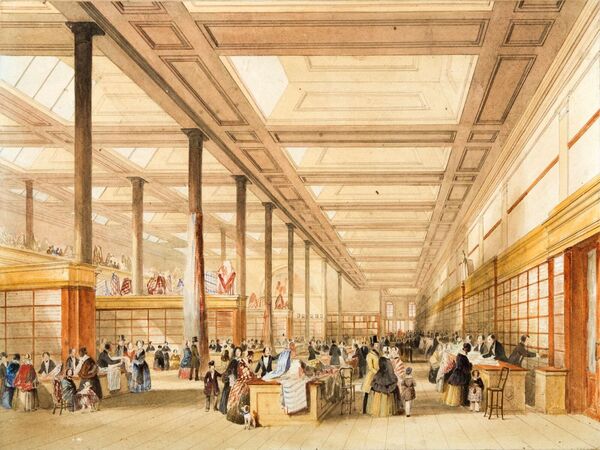

William Fitzgibbon, a native of Rathkeale, Co. Limerick, began a drapery store in Mallow Lane (now Shandon street), and proved a great success. After a few years he transferred the business to George’s Street, now Washington Street. Here his success continued until Fitzgibbon conceived the daringly ambitious project of acquiring and roofing in the entire block, bounded by the South Main street, Castle street, Grand Parade, and Brunswick street. Bit by bit he acquired leasehold and fee-simple properties, including the disused Cork Courthouse. Work commenced in 1844, and in 1846 the new warehouse was ready for occupation. It was a signal and instantaneous success.

Cork can reasonably claim to be the pioneer of monster warehouses in Ireland, England, or Scotland. The American Department Store was then unknown. All shops previous to this were specialised. For instance, you had milliners, costumiers, jewellers, hosiers, tailors, outfitters, silk mercers, stationers, house furnishers, ironmongery, baby linen, boots, Manchester goods, woollens, etc. He foresaw the advantages of the departmental system by introducing the different trades under one roof. In this way the Queen’s Old Castle was the first fully equipped monster warehouse in the Kingdom.

William Fitzgibbon went into the Corporation, became Mayor of the city, and distributed the entire salary of chief magistrate during his successive years of office between the charities of the city. Many of those trained under him afterwards attained high positions, not alone in the drapery, but also in the banking and industrial world.

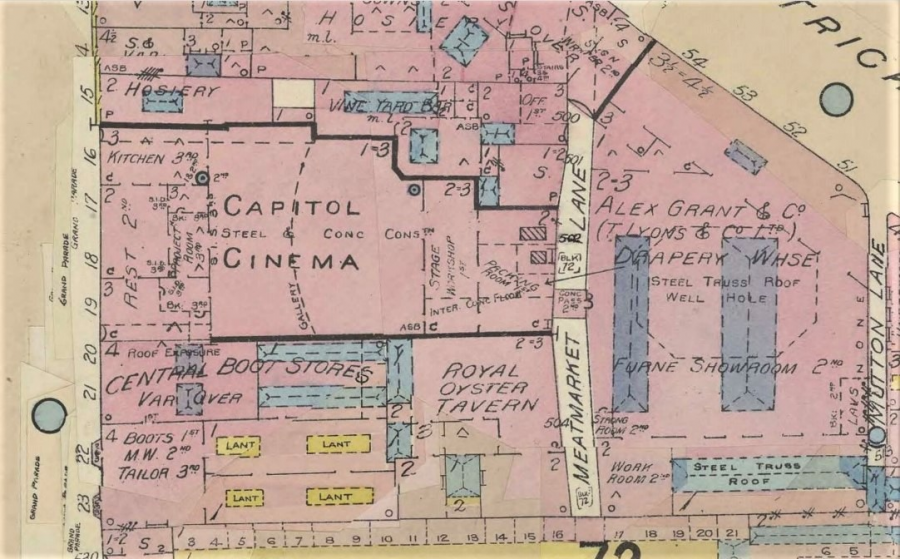

William Fitzgibbon was succeeded in the business by his son, Mr. Victor Beare Fitzgibbon. In 1873, in conjunction with Messrs. Alexander Grant and T Lyons, the business was converted into a limited liability company under the title of T Lyons and Co., Limited, the three gentlemen above named forming the principal members of the directorate, and, by a combination of the three houses on what was known a s the stores system, established a trade which in point of magnitude and volume has never before been equalled in the annals of commercial enterprise in the South of Ireland.

Creating Queen’s Old Castle Shopping Centre:

From the 1840s to the 1970s, The Queen’s Old Castle was in operation as a department store, and ownership changed hands a number of times over the decades.

The premises was eventually purchased by Power Securities Ltd, who made the change from department store to shopping centre. Former Taoiseach Jack Lynch opened the Queen’s Old Castle Shopping Centre on 7 May 1980.

There were dozens of individual shops, cafes and restaurants in the centre, with men’s and women’s clothing stores joined by jewellers, bookshops, galleries and more.

There was further change in 1996 when Clarendon Properties purchased the building. It shut for refurbishment and when it re-opened it was with two large tenants rather than many small stores.

The Virgin Megastore was opened by Roy Keane in December 1997, followed two month later by Argos. Virgin closed in 2009 and that store, which changed hands a number of times in the last decade, is currently a Dealz.

Cork shoppers will be waiting to see what’s next for the venerable old building.

VIEW more old pictures here: Picture special: Another twist in the Queen’s Old Castle tale (echolive.ie)

Bishop Lucey Park:

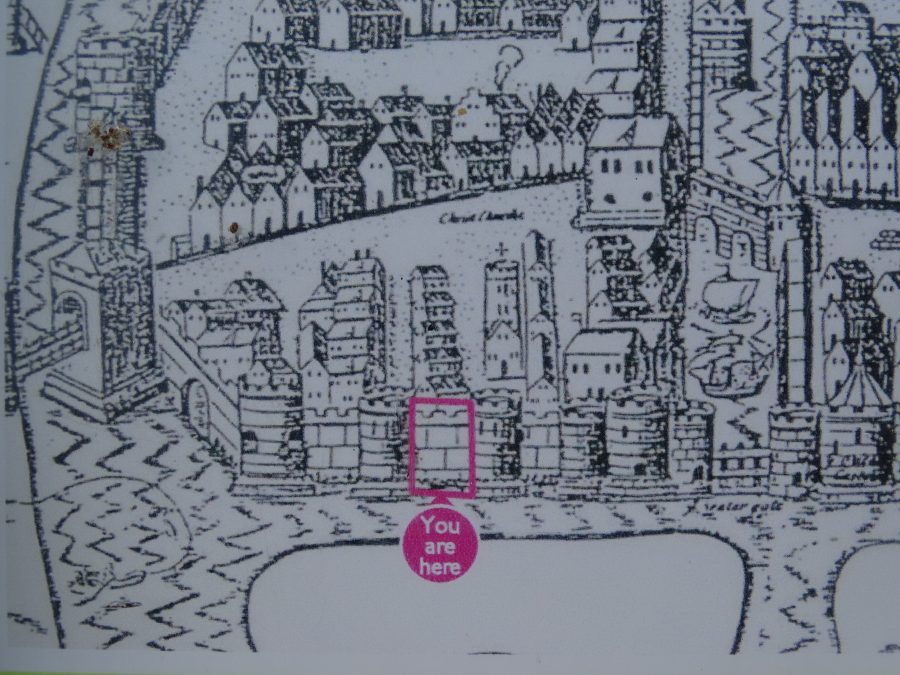

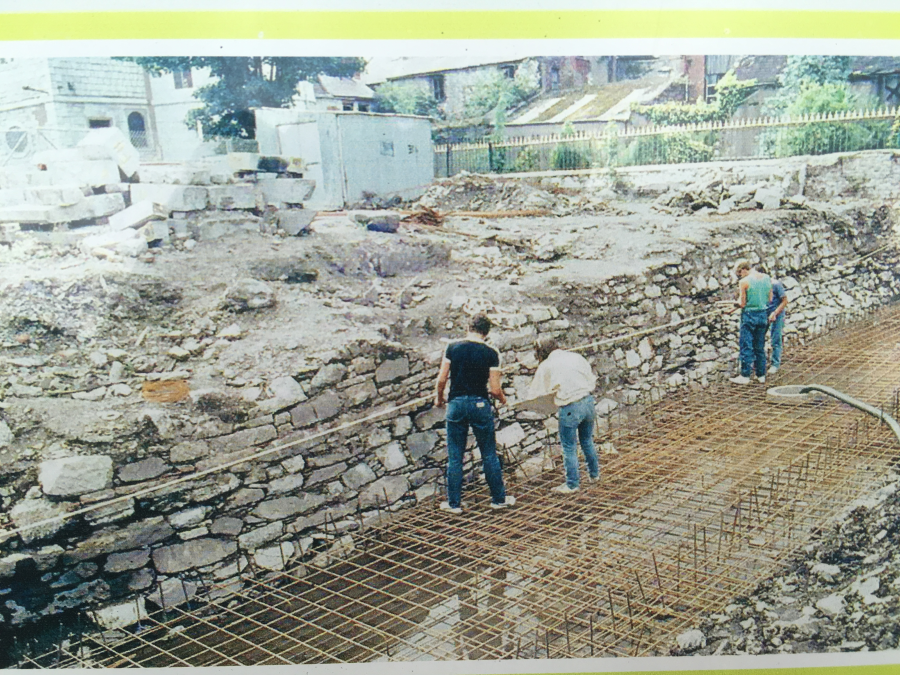

In 1984 / 1985, Bishop Lucey Park was created to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the granting of the first charter by King Henry II to the citizens of the walled town of Cork. Ironically, whilst preparing the ground for the park, a section of the imposing town wall was exposed, excavated and was added to the park.

WATCH a short news piece from an RTÉ News report broadcast on 10 June 1985. The reporter is Tom MacSweeney and features footage of the town wall find at Bishop Lucey Park. Click here: RTÉ Archives | Environment | Cork Heritage (rte.ie)

VIEW: Kieran’s stroll through Bishop Lucey Park

VIEW: GLOW – The Christmas Festival at Bishop Park hosted by Cork City Council; pictures by Kieran McCarthy

READ: Cork City Council and the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland (RIAI) have announced the winning architectural design of the competition to redevelop Bishop Lucey Park in Cork, Winning design unveiled for the redevelopment of Cork’s Bishop Lucey Park (irishexaminer.com)

An Upturned Canon:

In September 1690 a Jacobite army along with a number of Irish rebel factions combined forces to take control of Cork to provide a stronghold position against King William. The actual number of insurgents is not recorded, but it is likely that several hundred soldiers were involved in the takeover of the walled town. These forces were welcomed by the Catholics in the area. They manned the drawbridges and the town wall-walks, readied numerous buildings and waited for the attack they knew must surely come.

In September 1690, King William despatched the Earl of Marlborough, and a large contingent of men to regain control of Cork. On Monday, 22 September 1690, Marlborough arrived in Cork Harbour with over eighty ships and approximately five thousand men. Marlborough decided that he could exploit the main defensive disadvantage of the walled area: its low-lying position overlooked by hills. Control of the hills would mean control of the walled town.

On Saturday, 27 September, the bombardment of the city escalated. The cannons concentrated on breaching the eastern wall, a point now marked by the City Library on the Grand Parade. After a few more days of sustained attack, the rebels within the walled town surrendered. The principal rebel leaders were transported to the Tower of London.

Today, two interesting remnants of the Siege can be seen in the city. On the corner of Grand Parade and Tuckey Street, embedded into the pavement, is a cannon that was reputedly used in the battle; it is thought that it was later used as a mooring post for a quayside in the 1700s. The second is a cannon ball fired from Elizabeth Fort at the tower of St FinBarre’s Cathedral. During the rebuilding of the cathedral in 1735-1738, this twenty-four-pound cannon ball was found embedded in the spire, about ten metres from the ground. It is on display in the ambulatory of the present cathedral. The siege proved to be a major catalyst in initiating change in the physical and social landscape of the walled town.

Picture: Canon, Grand Parade during renovation works – reputedly used in the Siege of Cork, 1690 and subsequently as a mooring post for ships when the Grand Parade was a canal (picture: Author)

Mapping the Grand Parade:

The damage from the Siege of Cork in 1690 was significant. Cork’s town walls lay heavily broken down and houses has been raised to the ground. The decision to take down the town walls and to leave the town to expand on expanding marshes was not taken likely and it was a process that took 50 years.

The Quaker family of Tuckeys led the way in the taking down of their south east town wall section. The first member of the Quaker Tuckey family arrived in Cork in the army of Oliver Cromwell. A leading figure in the parish of Christ Church, Timothy Tuckey Senior died in 1668, and was interred in a vault in the crypt of the Church. Tuckey’s son Timothy was elected Mayor of Cork in 1677, and it is after him the lane and subsequent street was named.

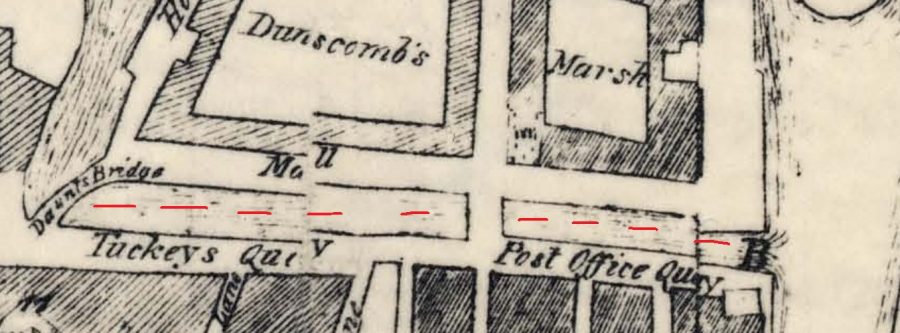

Tuckey’s Quay:

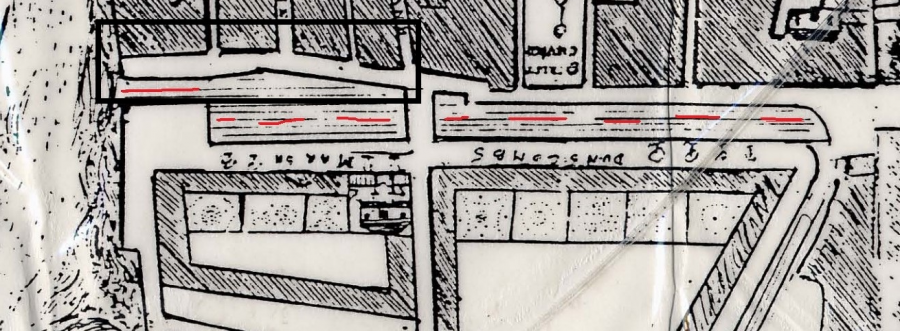

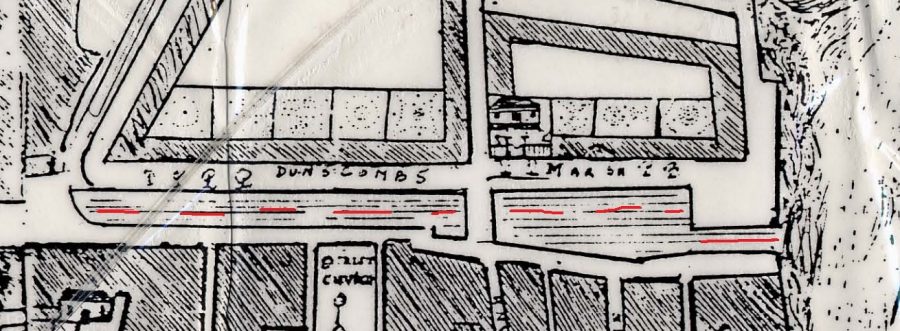

Circa 1694, Ormond’s Quay outside the town wall was leased to Alderman Timothy Tuckey for 99 years at a yearly rent of eleven shillings. It became formally known Tuckey’s Quay (now City Library section of the Grand Parade to Tuckey Street). A year later in 1695 Timothy Tuckey was given liberty to build houses on the Quay providing he left twenty feet clear in breath of the quay. Over the ensuing ten years, Timothy Tuckey also took down several sections of the town wall to its foundations.

Tuckey’s Bridge:

One particular and significant venture, which was recorded at length in Cork Corporation’s council books, was the agreement between Alderman Tuckey and the Dunscombe Quaker family in 1698. In mid-January 1698, Captain Dunscombe was given liberty to build a stone bridge from Tuckey’s quay onto his leased marsh. The Corporation of Cork required that the new bridge have arches high and broad enough for a small boat to pass under at high tide and must be kept in repair by the Dunscombe family and their heirs. Berwick Fountain is the exact site of Tuckey’s Bridge, which spanned a canal at that place, and on which the equestrian statue of George II was first erected.

The Post Office Quay:

Maps from 1750 t0 1773 show the emergence of the placename Post Office Quay and a post office. Little history has survived on the nature of the post office building but it does have a large footprint on the maps. Between 1759 and 1773, the canal in front of Tuckey’s Quay was filled in as was Daunt’s Bridge on the canal.

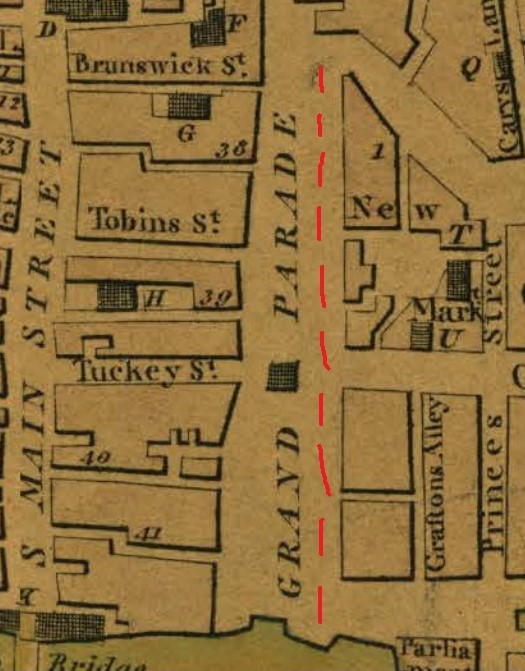

The Street of the Grand Parade:

Between 1773 and 1801, the Post Office Quay had been filled in and the broad thoroughfare of the Grand Parade emerged. The post office footprint is denoted as Old Post Office. it is known that the post office moved to the reclaimed eastern marshes,

The Street of the Yellow Horse, Grand Parade:

One of the more interesting felonies committed within the city centre in 1862 was the destruction of the hollow yellow horse of King George II at the intersection of the Grand Parade and the South Mall. A symbol of British colonialism in Cork, for just over one hundred years, it was to meet its demise in this year.

Originally planned for in October 1760, the Mayor Thomas Newenham, was announced that any subscriptions towards the creation of the statue of King George 11 would be greatly appreciated. In the same month, the statue was completed by designer Mr Van Oost and on 21 April 1760, the completed statue of King George, was landed at the city’s eighteenth century Custom House (now part of the Crawford Art Gallery, Emmett Place).

In late August 1760, it was decided to erect the equestrian statue with its pedestal on a specially constructed arch on the south side of Tuckey’s Bridge (centre of present day Grand Parade and marked by Berwick Fountain). In late September 1760, it was further decided to enlarge this bridge so that carriages can pass on each side of statue.

In mid-February of the following year, 1761, cast iron rails around the proposed site were attained and a cast iron copy of the Cork of Arms was attained. However, it was only in the following year, 1762 that the leaden Statue of King George II was actually placed on Tuckey’s Bridge.

The statue was eventually moved to its nineteenth century location c.1860 when Berwick Fountain was constructed on the site. The Fountain is named after Walter Berwick who came to Cork to preside as Chairman of the quarter sessions. He gave a gift of the fountain to the city. Sir John Benson was given the honour of designing the fountain and took six months to come up with a plan. On 27 August 1860, Cork Corporation laid the foundation stone of Berwick Fountain.

George II Statue on the corner of the Grand Parade and South Mall, c.1830 by W H Barlett in G N Wright’s Ireland Illustrated (1830).

On 9 March 1862 during the middle of the night, it is reputed that a person climbed over the security railings around George II and hacked away the supporting metal beam holding the hollow horse in place. The horse collapsed into the adjacent street and was hacked apart and broken into pieces by the general public. Part of the pedestal has survived the test of time is on display at the hall entrance of the present city museum in Fitzgerald’s Park.

The Irish derivative on the placename plaque for the street is Sráid an Chapaill Bhuí or Street of the Yellow Horse.

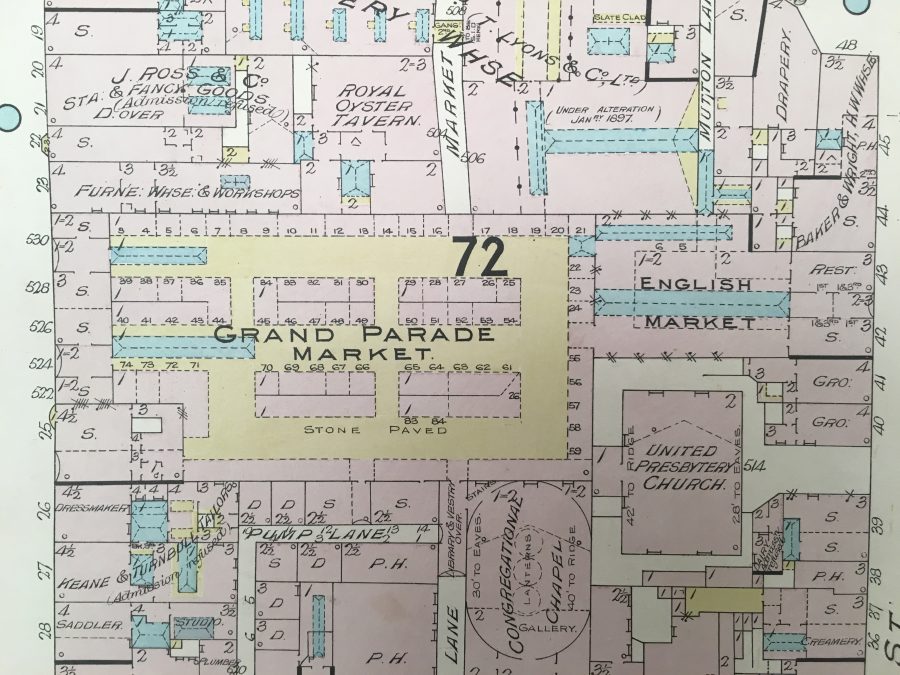

English Market:

The English Market was opened in 1788 and was known then as the root market. Today Corkonians know the market under several names: The Princes street market, the English Market, the Grand Parade market or some call it ‘de market’. By the mid-1800s, the market had fallen into a state of disrepair. In 1862 the market was rebuilt under the direction of architect sir John Benson. the renovations were considered very successful.

The market has suffered two fires, one in 1980 and the other in 1986. After the 1980 fire, the market was again renovated at a cost of £500,000 and once again it was considered a great success, some of the original features were retained even. the fire of 1986 caused an estimated cost of £100,000 worth of damage. nevertheless, the market was again repaired. A characteristic of the market is the selling of tripe and drisheen, which are both traditional foods and have been eaten in Cork for centuries. Drisheen is extra special as it is indigenous to Cork.

VISIT the website of the English Market: English Market – Cork City Council

VIEW: The English Market by Discover Ireland:

St Augustine’s Church:

A report on the “State of Popery” in 1766 also describes an Augustinian Friary in Fishamble Lane. This lane no longer exists but in present day terms was located near present day Liberty Street. In 1770, their chapel was in a very bad state of repair. The head of the order Fr Edward Keating selected a site in the parish of SS Peter and Paul but this was rejected by the Bishop. He stated that a new chapel could not be built in this Parish or in the Parish of Shandon due to the presence of other chapels and convents. Hence a new site was chosen in the South Parish on Brunswick Street. On 20 November 1780, the foundation stone was laid. Seven months later on 4 June 1791, the bishop complied with the Rome mandate by opening the church in the presence of Fr. Edmund Keating himself.

In 1791, the Augustinians rented land from a nearby grocer where they built a new sacristy. In 1872, the Augustinians built two new priory houses on Great Georges Street. With the growth in population, it became clear that the chapel would have to be extended again in order to cope with the crowds. However, a shortage of funds meant building could not take place. Approximately, fifty years later, the finance was finally raised and in 1944, the present-day church was opened.

Today’s church took seven years to complete. During these years, a major problem encountered, involved the marshy land on which the building was to be constructed. In addition, the lack of raw materials for building existed. This was due to the Second World War which restricted the supply. Consequently, there was a severe shortage of steel for the roof and stone. Stone had to be attained from the blown up remains of a stone viaduct in Mallow. The design chosen was one of a Roman Style.

An absence of pillars means the altar can be seen from any part of the interior. The doorway adjoining Washington Street today was designed in an Italian style. Its sculptor was Mr Christopher Fitzgerald. The lack of funds led to many unconstructed features. For example, at the entrance from the Grand Parade, a large bell tower was supposed to form an elegant entrance. Today, a narrow tunnel forms the Grand Parade entrance instead.

Finn’s Corner:

The Finn’s Corner business was founded by Drinagh draper, William Thomas Finn. The landmark shop, was ran by the Finn family for over 140 years and including former Irish rugby legend Moss Finn as a co-director jointly with his brother Will, The business closed in 2020 and awaits a new owner.

READ more here: End of an era in Cork as Finn’s Corner to close doors as building sold (irishexaminer.com)

Singer’s Corner:

The foundation stone for the Singer’s Corner terrace was laid in 1827 and the Singer Sewing Machine Company moved into No 1 Washington St, a late Georgian building, between 1873 and 1875. The building was the headquarters of the Singer Company in Ireland and every floor was in use for offices and workshops.

In 2014, Johnny Bugler, a member of Cork Printmakers, is leading a team of four artists — Conall Cary, Fiona Kelly, Dominic Fee and Cathal Duane — who are painting a striking black and gold Chinese-inspired floral motif on the historic end-of-terrace building on the junction of Washington St and Grand Parade.

VIEW an interview with Artist Johnny Bugler on the mural at Singer’s Corner by the Irish Examiner:

The Square and Compass, Masonic Hall:

The Masonic Hall is located at 25-27 Tuckey Street. This building has been the headquarters for Freemasonry in the province of Munster (County & City of Cork & County Kerry) since 1844. This is an end of terrace, seven bay, four-storey building, with a slate pitched roof. Archival material on the walls of the Lodge denotes that it was built c.1770, in the then recently developed Tuckey’s Street (1761) and is shown as ‘The New Assembly Rooms’ on a city map of 1771.

The ground, first and mezzanine floors of this building were constructed at this time: there were 3 shops on the ground floor, generating income for the maintenance of the building, while a sweeping staircase led to the Assembly Room (now the lodge room) and upward to the gallery (now a storage room). The upper floor was available for rental by various societies and clubs, among them the First Lodge of Ireland which, in 1844, purchased the entire building for its use, and that of the quarterly general meeting of the province.

In 1925, when all other city lodges came together at this premises, the top floor was added (now Royal Arch Chapter Room) to provide additional capacity. From the outside this building may seem unassuming, even austere, but behind its walls lies an interior of vast beauty and history.

In the Supper Room on the ground floor there are many display cabinets containing historic items relating to important events in the life of the Masonic Order in Cork, Ireland, and overseas, including old Masonic aprons, levels and badges dating back to the eighteenth century. One of the levels displayed there was used at the laying of the foundation stone of St Patrick’s Bridge and St Fin Barre’s Cathedral. A section of this room is devoted to the Hon. Mrs Elizabeth Aldworth (nee St Leger) who was reputedly the only female ever to be admitted to the Masonic Order.

The Lodge Room is reached via the original 1770 staircase, which is lined with fascinating pictures depicting many important historical events in Cork City. On entering the Lodge Room it feels as if one has stepped back in time. The stalls and paneling are over 300 years old having come from the former St FinBarre’s Cathedral (demolished 1865). The armorial banners on the walls are the coats of arms of some of the highest-ranking members in the Freemasons; those over the stalls belong to current stall holders, while those higher up towards the ceiling belonged to members now departed.

The figures which surround the large mosaic are the plaster casts used in making the figures of the four Evangelists which surround the west window in St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, and examples of craftsmanship by Cork firms past and present are on display on all sides. The Lodge room is used every month from September to May by the seven Lodges, which meet in Cork City.

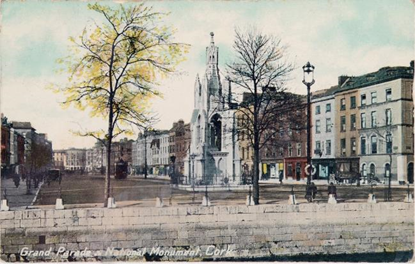

Berwick Fountain:

The fountain is named after Sergeant Walter Berwick who came to Cork to preside as chairman of the quarter session courts in the city which were held every season in the 1850s. Berwick was a comical and popular man and came up with the idea of financing to the city a drinking fountain. He gave £350 to finance the cost of it, just before he departed from his position. The Corporation of Cork approved and Sir John Benson was given the honour of designing the fountain and took six months to come up with a plan.

On 27 August 1860, Cork Corporation laid the foundation stone of Berwick Fountain. The builders never finished the fountain completely as one part did not arrive on time and is still missing today. Where the pipe protruding up at the top of the fountain is, is where Benson’s figure of a little boy with a water lily was supposed to be located.

Cork School of Music:

On 24 March 1876, a committee was appointed at a public meeting held in the Royal Cork Institution aiming to establish Schools of Science, and Music and a larger School of Art in Cork. The School of Art Headmaster James Brenan and architect Arthur Hill were the honorary secretaries of this committee. In the same month, the managers of the Royal Cork Institution sent a petition in favour of establishing such latter schools to the Committee of the Council on Education at the Westminster Department of Science and Art in London.

A public meeting of Cork citizens was held, to discuss the establishment of a School of Music. A Cork member of parliament proposed in the Westminster Parliament a Cork School of Music. Under the Public Amendment Act (Ireland) 1877, the same conditions were granted to music as were passed in 1855 to science and art.

Early in 1878, the Cork Borough Council, in accordance with this Act, appointed a permanent committee. The Council assigned to them an income to the full extent permitted by the legislature, and opened the School of Music in temporary premises at 51 Grand Parade. The funds from the Borough Council were augmented by many generous subscriptions. The School of Music made remarkable progress and in 1890 was moved to Morrison’s Quay. Music was incorporated in the national educational scheme of 1900. In 1902, the School was moved to larger premises on Union Quay.

The Early Days of the Cork IDA:

Inspired by the efforts of the Cork International Exhibition, on 7 May 1903, a public meeting was held at the Chamber of Commerce premises on St Patrick’s Street, for the purpose of forming a permanent industrial association for the city and county, and to put forward the interest of Irish manufactures and products. A meeting of the Council of the new association – the Cork Irish Development Association – was then held on 27 May at their rented offices at 13 Marlboro Street, Cork.

Those present were leading merchants and politicians in the city. Mr George Crosbie, chairman, presided, and the other members present were: Messrs W B Harrington, honorary treasurer; Augustine Roche, J McFerran, C M O’Connell, Michael Egan, George Coates, C J Dunne, Charles MacCarthy. J O’Brien, P Cahill, Diarmuid Fawsitt and William Roche, Honorary Secretary.

On the recommendations of the sub-committee Mr E J Riordan was unanimously appointed to the post of secretary and organiser of the association. It was decided that manufacturers be required to pay an annual subscription of not less than one guinea and ordinary members an annual subscription of not less than one shilling.

The Cork IDA soon included important Irish manufacturers and traders. They insisted on they themselves buying Irish-made goods and persuading others to do likewise. They held meetings throughout the country and within a few years similar bodies were established in Dublin, Limerick, Belfast, Galway and Derry. One of the chief successes was to gain legal recognition for the Irish National trademark, Déanta in Éireann (Made in Ireland), which went far towards preventing the bogus sale of so called Irish products.

With the help of John Boland MP for Kerry, advantage was taken of a new bill, which made it possible to register and enforce a national trademark. The Cork IDA instituted numerous prosecutions, which soon restricted the previous abuse of Irish names and labels. It also gave help to firms, which were willing to start new industries in Ireland.

By 1920, the Cork IDA offices were at 27 Grand Parade.

By 1949, the regional IDA branches merged under the umbrella of IDA Ireland.

The Grand Parade, 100 years ago:

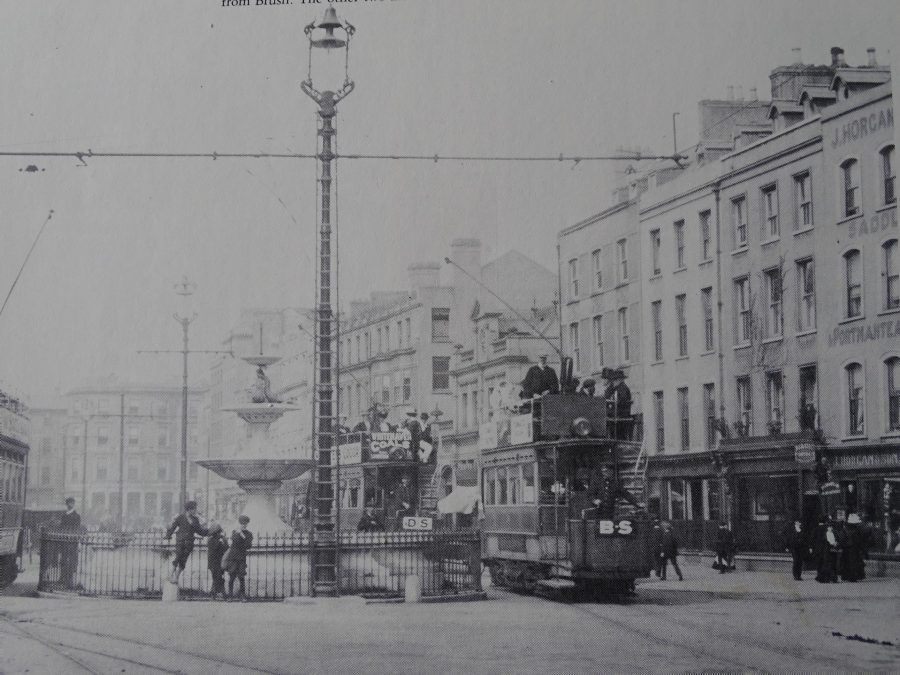

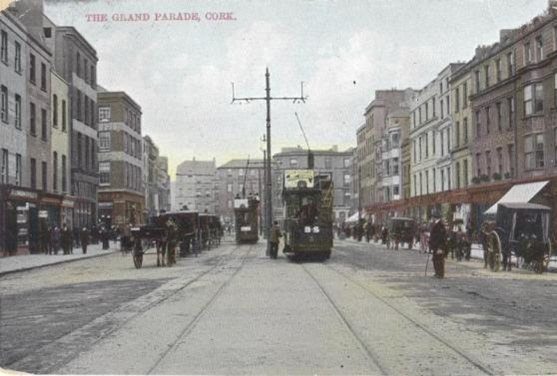

In 1911, the businesses that extended from the corner of St Patrick’s Street to the buildings at the right of the postcard included: The Mexican Tobacconist, Murray’s Stationers, The Central Dairy, Butterfield’s Dentistry, Gabriel’s Hosiery, Foley’s Confectioners, Post Office, Music Supply Stores, Smith’s Hosiery, Elliott’s Dress Warehouse rooms, Bollar’s Baby Linen Warehouse, Munster Boot Company, Cudmore’s Fruiterer, Greig’s Tailor and Clothier, Murphy’s Shirtmaker and Hosiery, Grant’s Furnishing Warehouse Rooms, Wolfe’s Outfitters, Lebin’s Millinery warehouse rooms, and Central Boot Stores.

The central feature of the postcard below is the English Market. To the right of the site, the businesses included Hill’s Hosiery, Swales’s Dentistry, Shinnick’s Costumiers and Milliners, Keane & Turnbull’s Ladies Tailors, Murphy’s Dress and Mantle Rooms, Guider Millinery warehouse rooms, Horgan’s Saddlers, Shandrum Dairy, O’Sullivan’s Jewellers, and McGrath’s Dress Warehouse Rooms. In recent years, the public space on the Grand Parade has also been redesigned by Catalan Architect, Beth Gali.

Grand Parade, c.1900 from Kieran McCarthy’s and Dan Breen’s Cork City Through Time (2012, Amberley Publishing)

VIEW: Cork’s Grand Parade, filmed by Mitchell and Kenyon, c.1901

The National Monument:

The National Monument on the Grand Parade honours the Irish patriots who fought in rebellions. An inscription on it reads: “To perpetuate the memory of the gallant men of 1798, 1803, 1848 and 1867 who fought and died in the wars of Ireland to recover her sovereign independence and to inspire the youth of our country to follow in their patriotic footsteps and imitate their heroic example. And righteous men will make our land A nation once again”. Several lists of names are recorded on the monument, which features five statues: Mother Erin; Wolfe tone, the leader of the 1798 rebellion; Fenian leader Peter O’Neill Crowley; Young Irelander Thomas Davis; and United Irishman leader Michael Dwyer.

Picture: Maid of Erin, National Monument, present day (picture: Author)

The foundation stone was laid in 1898, close to where a statue of George III on horseback once stood, but the finished structure was not unveiled until St Patrick’s day 1906. unveiled by patriot Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa from Rosscarbery, County Cork, the landmark monument became a regular meeting place for many nationalist political meetings over the years.

VIEW Kieran’s short film around the National Monument, Grand Parade:

The Shamrock Hotel:

Cappoquin born Michael O’Donoghue was a final year student in early 1921, who was studying for his Batchelor of Engineering degree (mechanical and electrical) in UCC. He was Engineer Officer of the 2nd Battalion, Cork IRA Brigade No.1. In his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History (WS1741), he provides insight into his life going between student and IRA member.

During January and early February 1921, Michael kept a Colt .45 with ammunition in his lodgings in the Shamrock Hotel at 31 Grand Parade. The Shamrock was located above Miss O’Brien’s Restaurant. Many a night the landlady Mary O’Brien took the gun from him and concealed it herself during the long night hours, handing it over to him in the morning. There were a number of IRA men in the building sharing its 6-8 bedrooms, including her own brother.

However, the 1921 Martial Law Ordinance decreed that all heads at households had to list the names and occupations of all those residing in their house and that they should hang this list for military inspection on the inside of the front door. Absentees or fresh arrivals or new residents were to be especially noted. The penalty for evasion of this blacklisting decree was all the rigours of a British military court martial. Miss O’Brien had complied, as did every other householder.

One day when Michael was at the university, a British military officer with about ten armed soldiers visited 31, Grand Parade. The officer removed the list of names, questioned Miss O’Brien about the then whereabouts of all the residents – who were out and noted the names of the men who were in. He ordered Miss O’Brien to show him to the rooms of these in turn, leaving his armed soldiers below in the hallway and at the door. He queried each man of those in about his name, age, occupation, and reason for being in, and checked, with particulars on list. Satisfied, he returned the sheet to Miss O’Brien and withdrew with his troops.

That night Michael remembers he kept the gun loaded in his overcoat pocket hanging in the wardrobe of his room. He shared the room with Mick O’Riordan, an IRA man with B-Company, 2nd Battalion, who worked as a draper’s assistant over in the South Main Street.

The night passed without incident and next morning he brought the gun, loaded and all, with him to the Crawford Municipal Technical Institute where he was to do some practical work and study in the electrical laboratory.

Cork City Library:

The first public library in Cork was formed in 1893 on Emmett Place. The purpose-built Carnegie Free Library, which opened on Anglesea Street in 1905, included a dedicated children’s department and reading room. Fifteen years later, the library became a casualty of reprisal burnings by Crown forces in the city on the night of 11 December, 1920, at the height of the War of Independence. The building and the stock on site – approximately 14,000 books – were engulfed by the fire in the neighbouring building, the City Hall. Considering the competing urgent demands placed on the local authorities in the wake of this decimation of the city centre, that a library service was re-established on a temporary site in Tuckey Street was due largely to the herculean efforts of the then librarian, James Wilkinson.

Wilkinson issued an appeal for book donations which yielded an extraordinarily generous response from the national and international community. The accession ledgers in which acquisitions to stock were recorded continue to be housed by the Central Library’s Local Studies Department and make for fascinating insight into the history of reading in Cork city.

Some notable donors were Charlotte Bernard Shaw, wife of the playwright George Bernard Shaw; Mrs W B Yeats, wife of the poet, and novelists Edith Somerville, Lennox Robinson, Daniel Corkery and Annie M P Smithson. A letter written by Wilkinson in 1923 to the superior of St Brigid’s Convent, Sydney, apologising for the delay in acknowledging receipt of the order’s financial donation, captures the turmoil of this historic period: the delay “was due to the fact that the cheque and list of donors was transmitted by Professor A O’Rahilly at a time when he was an interned prisoner, who sent the cheque on to me, but not the list of names.”

The library transferred to its present location on the Grand Parade in 1930 but a curious relic of the Carnegie Library may be seen on Tuckey Street. Two pillars embossed with the Irish language translation of Carnegie Library on the cap stones are visible, though, as set back from the street, largely unnoticed. Whether these were salvaged from the library after the burning, or how they were conveyed to their present location, is unknown.

The Capital Cinema:

On April 5, 1947, one of Cork’s best-loved buildings opened its doors for the first time. In 1989, to fight back against the popularity of TV and videos, the cinema closed for six months for major reconstruction. It became the Capitol Cineplex, the first multi-screen cinema outside Dublin, a 1,100-seat, six-screen theatre that served the cinema-going public in Cork until its closure in 2005.

The redevelopment of the Capitol site was one of the most significant retail projects in Cork city in this decade and was completed in July 2017.

READ MORE: Nostalgia: Capitol cinema was one of Cork city’s favourites, Nostalgia: Capitol cinema was one of Cork city’s favourites (echolive.ie)

READ MORE with Ellie Byrne, Our picture-perfect memories of Cork’s Capitol Cinema, Our picture-perfect memories of Cork’s Capitol Cinema (irishexaminer.com)

VIEW: Construction timelapse video of The Capitol retail and office development in the heart of Cork City.

The City Club:

This impressive dwelling was formerly home to the Cork City Club and dates back to the early days of the 1800s, and was considerably renovated in 1860 to create the additional pediments designs. It was a Victorian gentleman’s Club called Cork City Club with card room spaces and billiard rooms.

In 1952, Cork City Club and Cork County Club were amalgamated and opted to use the premises of the County Club on the South Mall. The City Club premises were put up for auction and purchased by the Legion of Mary, a lay Catholic organisation. The building was renamed Dún Mhuire and converted into the headquarters of the Legion in the Diocese of Cork. In later years the Legion of Mary departed the building, after which ICC Bank occupied the premises until 2001. A branch of the Bank of Scotland (Ireland) occupied the premises from 2001 until 2010. Certus, a bank services outsourcing group, occupied the premises from 2010 until December 2013.

The building is now the MTU city centre hub for postgrad fine art students with the MTU Crawford College of Art & Design on the Grand Parade.

LEARN MORE about MTU campus locations:

Munster Technological University – MTU – Cork Campus Locations

Nano Nagle Bridge:

The year 1985 coincided with a cause for much celebration in Cork City as it was the 800th anniversary of the granting of Cork’s first charter. Many events took place in the city and many developments were opened by the then Lord Mayor, Mr Liam Burke TD. One of these developments was the building of a new footbridge spanning the Lee near the National Monument on the Grand Parade to Sullivan’s Quay. The bridge itself was opened on the 14 June. It has a single arch design and was built by Site Services Ltd.

Agreement was reached to name the bridge after Nano Nagle who founded the Presentation Order of nuns in 1777. She and her associates worked to ease the hardship of the Penal Laws.

ENDS.