Background to Cork and its Railways (c.1800-1850):

As a port city, Cork has always had a strong tradition of people coming and going through the ages, all striving to make a satisfactory living in the rebel city. If anything, this is reflected in the varied architecture of the buildings of the urban area, in some areas the non geometrical pattern of streets, and then there is the thousands of merchant names, local and not so local, that appear in Cork street directories through centuries.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the division between the middle and poorer classes in Cork became wider. In general, the rich got richer whilst the poor got poorer. For the lower socio-economic classes, unemployment, slum conditions and emigration were all part of daily life. Without any enlargement of the housing capacity in Cork’s inner city, the poor were further concentrated in the former medieval area of North and South Main Streets, around Barrack Street in the southern suburbs, and Shandon Street in the northern suburbs. Many of the impoverished homes were located in narrow and very unclean lanes. The habitations varied from cabins to cellars, all in a poor and rundown state.

Individual fortunes providing provisions to the war between Britain and France, from 1805 to 1815 (Napoleonic) meant that the middle and upper classes were able to withstand short-term economic pressure. In the city there was an increased incentive to sell houses in the central area. With an increased population and a growth in the value of building land for shops and offices, more middle and upper class people began to move out to the already rich suburbs outside the city. As the nineteenth century progressed, these new middle class residence areas comprised Douglas, Ballintemple, the Mahon Peninsula and Montenotte.

As new residence areas emerged, new modes of suburban transport were created. County and national rail links were developed. By the late 1800s, there were five county railway lines and one national line, all of which operated in and out of Cork City.

The Great Southern and Western Railway:

The idea for the Great Southern and Western Railway (G.S. & W.R.) began in the 1840s and initially aimed to link Dublin to the southern provinces. The network was to cover 1,500 miles and the G.S. & W.R., were to become Ireland’s largest railway company.

In 1846, William Dargan, a highly successful contractor, was awarded the contract for the Thurles-Cork section of the line. Despite the difficult landscape conditions encountered, by 1849 the line had been constructed from Mallow to Cork. High embankments were needed along with three stone viaducts over the River Blackwater at Mallow, Monad and at Kilnap near Cork City.

The railway’s approach to the city quaysides was important. The initial route proposed was along the Blackpool valley (northern suburbs) and along the Kiln River. However, it was found that property acquisition was too expensive due to the built up nature of the area. The second route proposed involved a route up the Glen River Valley, one of the rivers that flows into the River Kiln in Blackpool, in what is now the Ballyvolane area. However, the landscape there was found to be too steep. A third alternative was proposed and adopted, that of a tunnel to be bored through a sandstone ridge.

Under William Dargan and Sir John MacNeil, the boring of the tunnel began in 1847 and took seven years to complete. A temporary terminus was built at Kilbarry to accommodate the Dublin-Cork Services. The tunnel had four ventilation shafts; two sunk on either side of what is now Assumption Road, one in Barrackton and the southern most shaft at Bellevue Park. These can still be seen today in the Montenotte –St. Luke’s area, under which the tunnel runs.

Work on boring within the tunnel was slow. On average just over a metre per week was bored through day and night shifts. Work was also was hindered by fatal accidents.

One such accident occurred on the morning of 13 March 1850 when explosives, which were used to clear rock, were mistimed and the blast killed two people and left many people injured. The two killed were from the heart of Cork’s Blackpool, Michael Driscoll, aged 24 of Broad Lane and John McDonnell, aged 30 From Foster’s Lane. To mark the tragedy, a plaque was erected by Blackpool Historical Society in association with Cork City Council, and located on the North Ring Road.

On 19 July 1854, the tunnel was completely bored through and was opened in 1855.

In the early 1850s, the viaducts between Mallow and Cork were put in place along with the bridges over the old Dublin Road and Spring Lane. In July 1856, the passenger building and train shed at Penrose Quay was erected. The was designed by architect Sir John Benson. Its centre-piece was a covered way, just over 60 metres wide and was supported by twenty Doric columns. The problem of building the station on slob land was overcome by piling foundations. Six hundred beech piles, all just under eight metres in length were piled. Over these piles, concrete was laid.

In 1866, the Cork, Youghal and Queenstown Railway whose trains ran into Summerhill Station, immediately north of Penrose Quay became part of the G.S. & W.R. Quay Terminus. By the end of the nineteenth century, it became necessary to replace the original Penrose Quay terminus with a larger station, Kent Station, which opened in 1893.

The original Penrose Quay Station later became a cattle depot and its Doric colonnade was demolished sometime between 1895 and 1896. A small number of associated buildings have survived. These comprise of the former station manager’s house near Penrose Quay of the shell at the former goods shed, adjacent to the Cork tunnel entrance.

In the foyer of Kent Station, one of the original engines manufactured for the G.S. & W.R. is on public display. Bury, Curtis and Kennedy of Liverpool made it. It weighs just over 22 tons and in its lifetime covered over 350,000 miles. It was withdrawn from service in 1875. It is on display on original G.S. & W.R. cast-iron rails.

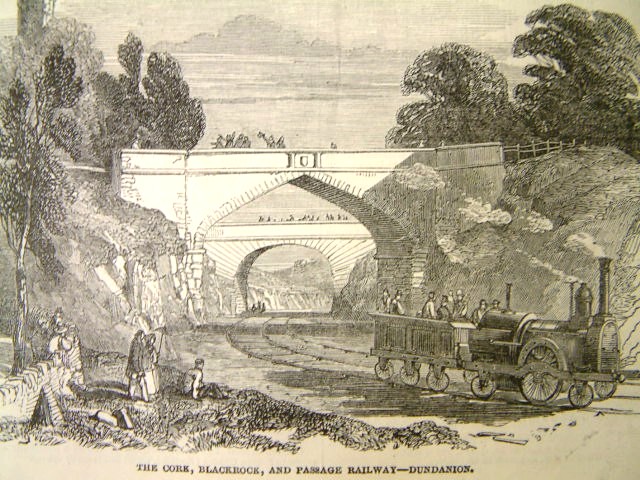

Cork Blackrock and Passage Railway:

The year 1834 marked the opening of Ireland’s first railway, between Dublin and Kingstown. A year later in 1835, the plan for a Cork Passage railway was first, proposed by Cork based merchant, William Parker and Cork solicitor, J.C. Besnard. In that year, Passage West had its own dockyard and had become an important harbour port for large deep-sea sailing ships whose cargoes were then transhipped into smaller vessels for the journey up-river to the city. This transhipment would be faster by train.

In the summer of 1835, a committee was set up to plan the railway and the Harbour Board, the treasury and other bodies were approached for financial support. The matter was deferred as it was deemed too late in that year to apply for an Act of Parliament to authorise the line.

Charles Vignoles was appointed engineer of the venture. The initial plan in 1836 was for the railway to go through Douglas and build a tunnel underneath Langford Row. However, it was eventually decided that it was cheaper and more level to construct the line along the south bank of the Lee. The line would run close to the south of the Navigation Wall (now the site of the Marina) on reclaimed land and remain close to the river to Passage.

Preparatory works immediately began at the Cork site and in 1837 the Passage Railway Bill was passed in the Westminster parliament. However, by 1838, the project was shelved due to the difficulty of raising finance and the worsening social conditions at the time. In addition, the main shareholders had lost interest and wanted their investments returned. The idea of a railway was abandoned.

In the mid 1840s, the railway project was resurrected. In 1845, legal powers were sought to establish three railways; Cork-Passage Railway, Cork, Blackrock, Passage and Monkstown Railway, and Cork-Kinsale Railway. In the case of the first two requests, their plans were amalgamated to form the Cork, Blackrock and Passage Railway Company in 1846.

The relevant legislation was passed in 1846 and in September 1846, the company’s engineer, Sir John MacNeill was employed to complete initial survey work. Patrick Moore won the contract for the first six miles of the line between Cork and Horsehead in passage. The cost of tender was £38,000 and work began in June 1847.

In the mid 1840s, the railway project was resurrected. In 1845, legal powers were sought to establish three railways; Cork-Passage Railway, Cork, Blackrock, Passage and Monkstown Railway, and Cork-Kinsale Railway. In the case of the first two requests, their plans were amalgamated to form the Cork, Blackrock and Passage Railway Company in 1846. The relevant legislation was passed in 1846 and in September 1846, the company’s engineer, Sir John MacNeill was employed to complete initial survey work. Patrick Moore won the contract for the first six miles of the line between Cork and Horsehead in passage. The cost of tender was £38,000 and work began in June 1847.

Due to the fact that the construction was taking place during the Great Famine, there was no shortage of labour. Huge numbers of unemployed people were attracted to the construction areas. In fact, trouble arose on more than one occasion with people who did not get jobs.

For example, on 21 June 1847, seventy out of two thousand men were hired. A week later, six hundred of those who did not get a job entered the site in protest. A total of 450 men were taken on for the erection of the embankment at the Cork end of the line. Another eighty were employed in digging the cutting beyond Blackrock.

The entire length of track between Cork and Passage was in place by April 1850 and within two months, the line was opened for passenger traffic. The Terminus, designed by Sir John Benson was based on Victoria Road but due to poor press was moved in 1873 to Hibernian Road.

In the late 1800s, the Cork Blackrock and Passage Railway also operated a fleet of river steamers in competition with River Steamer Company (R.S.C). The Railway Company expanded its fleet in 1881 but it was only when the service was extended to Aghada that profits grew. By 1932, the increase in the use of motor cars caused a decrease in the use of the line by passenger. Consequently, the railway was forced to close.

Much of the traces of the Cork-Blackrock line have been destroyed while the Blackrock-Passage section is now a pedestrian walkway with several platforms and the steel viaduct that crossed the Douglas viaduct still in public view.

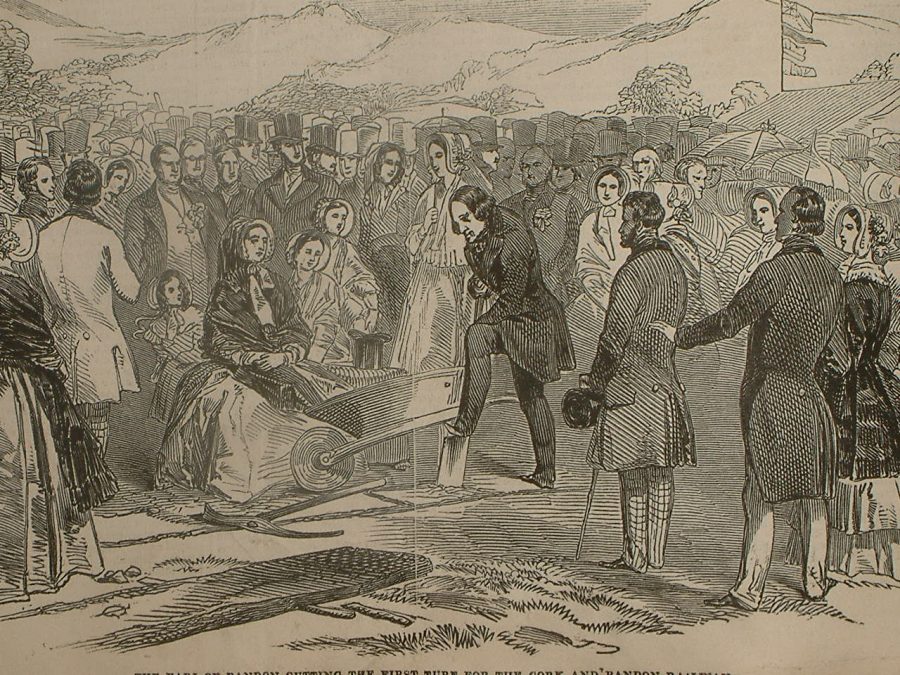

Cork Bandon and South Coast Railway:

Apart from the Cork Blackrock and Passage Railway, which linked the city to Cork Harbour towns by rail, another railway company operated a line connecting the south-west of the county to the city.

Engineer, Charles Vignoles, first proposed the idea of a railway that would connect Cork to Bandon in the Railway Commissioners report in 1837-38. In 1843, this idea was promoted strongly by Edmund Leahy who had just completed a county survey of the area and by local solicitor, J.C. Besnard. Consequently, in 1844, a provisional Bandon and Cork Railway Committee was established.

Charles Vignoles was appointed as the consulting engineer to survey and give his ideas on how to approach the proposed line. Besnard and Leahy became acting engineers and in 1845, the legislation was passed authorising the development to go ahead. In the same year work began on the Bandon to the Ballinhassig section. In July 1846, Leahy was dismissed for not ordering the right rails. Subsequently, Charles Nixon was appointed as acting engineer who had previously worked under an eminent British architect, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

A young Cork engineer named Joseph Philip Ronayne assisted Nixon. One of Nixon’s first proposals involved the adoption of cast-iron instead of timbers on the proposed Chetwynd Viaduct. He also proposed that tunnels should be bored at Goggin’s Hill and Kilpatrick instead of the deep cuttings.

The construction of the line was divided into six sections. Each section was the responsibility of different contractors. In 1849, due to financial difficulties, a decision was taken by company to open the Bandon–Ballinhassig line as fast as possible. Subsequently, it was opened in June 1849. In September 1849, the company chose a tender of £87,000 for the Cork-Ballinhassig section of line. The contractors chosen were Sir Charles Fox and John Henderson.

The Cork Bandon Railway Project was an enormous undertaking. The main parts included; a long railway tunnel at Goggin’s Hill; The Chetwynd Viaduct; a short tunnel bridge under old Blackrock road near the Albert Quay Terminus; 21 cuttings; 19 embankments and 15 road bridges.

One of the greatest problems was the construction of the Ballyphehane embankment. It was just over nine metres high and crossed the Tramore River’s floodplain. The track crossed the river initially on a wooden bridge, which in time was replaced by a stone culvert. On the southern approach to the city, it became necessary to cut deep through and into the limestone bedrock. The line also cut across three south-eastern approach roads which led into the city itself.

The entire stretch of line between Cork and Bandon opened to the public on 6 December 1851. The Cork terminus for the Cork Bandon and South Coast Railway was also completed in this year at Albert Quay. The main building is now the parking fines office on Albert Quay, next to City Hall. The old terminus had three passenger platforms, a carriage storage area, and sidings into the Cork Corporation’s stone yard and into the corn market.

In 1869, a goods siding was added and in 1875, a siding for carriage repairs added. However, it never had locomotive sheds until later years. Feeder lines were also added in the early twentieth century to the roller-milling complex on Victoria Quay and to the Ford tractor works on the Marina.

The first locomotive to operate on the Ballinhassig-Bandon line was manufactured by W.B. Adams of the Fairfield Works, Bow in London. On the Cork –Ballinhassig line, the Vulcan foundry of Newton-Le-Willows in Britain provided the first locomotive. Between 1852 and 1894, a further 25 engines were acquired by the company.

Between 1851 and 1893, the mileage of the West Cork Line extended from 20 to 94 miles. Many West Cork Towns attained their own railway stations; Kinsale (1863), Clonakilty (1866), Dunmanway (1866), Skibbereen (1877), Bantry (1881), Timoleague and Courtmacsherry (1890), Bantry Bay (1892), and Baltimore (1893).

In 1898, the Cork and Bandon Railway, the Cork and Kinsale Junction Railway and the West Cork Railway amalgamated together to form the Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway. This company further amalgamated with the Great Southern and Western Railway in 1925. The last passenger service to West Cork ceased in 1961. In 1979, the track bed approaching the city was widened for construction of the South Link Road as far as the former Macroom Junction in Ballyphehane.

5

Cork, Youghal and Queenstown Railway:

Between 1854 and 1862, a rail link was constructed between Cork and Youghal. It was supposed to be the southern half of a proposed line between Waterford and Cork. The full line though was never constructed. Independent companies eventually completed the Waterford and Tramore section and the Cork-Youghal section. In the case of this latter section, work was sanctioned by Parliament in 1854 and a branch line to Queenstown was sanctioned in 1845.

The first section of line to be constructed between Midlelton and Dunkettle was awarded to Moores of Dublin who proved problematic and were replaced by R.T. Carlisle of Canterbury. This line was opened in November 1859, taking three years to complete. As a temporary measure, Cork bound passengers continued their trip in horse-drawn omnibus. By May 1860, line had seen completed to Youghal and to Tivoli in September. Eventually, in December 1861, the entire line was completed and first locomotive left Cork for Youghal.

The initial location of the proposed terminus was at the corner of St. Patrick’s Hill and MacCurtain Street, then known as King Street. The selected location though was at Summerhill, on a rock cut ledge overlooking the Lower Glanmire Road. The terminus could accommodate two tracks, a simple station house, a goods shed and single passenger and goods platforms. Leaving Cork, the line ran parallel with Glanmire Road as far as Tivoli where the road crossed over it.

Access to important residences on north side of line was also facilitated by three ornate cast-iron footbridges, which were supported on large brick columns. These still exist today. In addition, the Cork-Youghal line had ten locomotives. Neilson and Co. of Glasgow built them all between 1859 and 1862.

In March 1862, the Queenstown branch opened but from here on in, the profits were hindered by financial problems. Eventually, the railway was sold to the Great Southern and Western Railway in 1865 for £310,000. From 1868 onwards, the Cork Youghal and Queenstown line could be taken at Penrose Quay. A connecting line was constructed at Grattan Hill. This crossed over a specially constructed lattice girdened (check) bridge, which also spanned Hargrave’s Quay.

Until 1877, a direct route could be taken from Queenstown to Dublin – Kingsbridge. The Summerhill station closed in 1893 and in February 1963, passenger services to Cork and Youghal discontinued. In 1992, Iarnród Eireann began to remove the rails on certain sections of the Cork-Youghal line. In recent years, the Cork-Cobh line has been re-established.

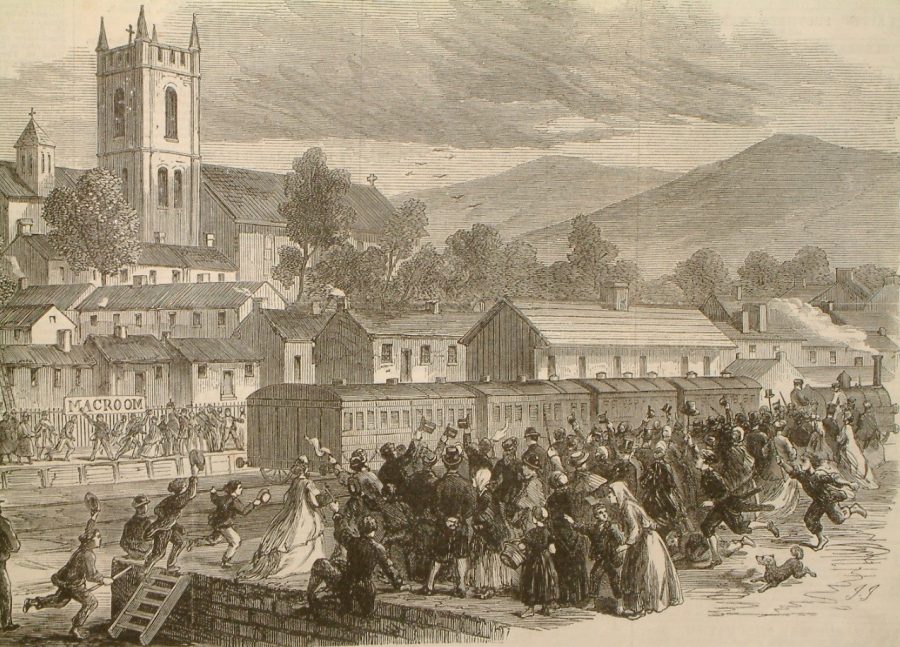

Cork and Macroom Direct Railway:

Sir John Benson, an eminent Cork City architect and engineer, initially proposed the Cork and Macroom Direct Railway. It was incorporated in 1861 and was chaired by Sir John Arnott and Joseph Ronayne. The first eight miles was bought in 1863 under the Cork-Grange division. The foundation on part of this section comprised of logs lying beneath the track. This underlay a section of slob-land near Wilton.

Five stations lined the 37-kilometre track and the line cost £6,000 per mile. The line was opened in May 1866 and in agreement with the Cork Bandon and South Coast Railway Company utilised the terminus at Albert Quay. However, in the 1870s, the company built its own terminus. Nearly a kilometre of an extension was sought and attained from Parliament. This extension connected Cork-Macroom line’s junction with the West Cork line at Ballyphehane to the site of the proposed terminus at Summerhill South.

The station was opened in September 1879 at a cost of £28,000. The station possessed two passenger platforms, an engine shed, and a repair depot. Draught horses were used for shunting wagons and carriages within the station’s precincts. This was to utilise power efficiently.

In 1925, the Cork-Macroom Railway Company amalgamated with the Great Southern Railway and the Summerhill terminus closed. Trains to Macroom ran from Albert Quay. In 1929, the station buildings were acquired by the Irish Omnibus Company and eventually by C.I.E., which still retain the site. The main brick – two storey office buildings still survive. Between 1866 and 1925, the company had six locomotives, over 27 coaches and over 117 wagons. One of the original engines was manufactured by Dubs. & Co. of Glasgow. The Cork-Macroom line eventually closed in 1953.

Cork and Muskerry Light Railway:

The Cork Muskerry Railway was one the city’s first narrow gauge lines. It was established with the help of the Tramways and Public Expenses (Ireland) Act of 1883, which enabled companies to obtain part or all of the finance to construct a line. The main beneficiaries were the Cork and Macroom line railways and the Schull and Skibbereen Line.

Primarily, the line was built for tourist reasons. It was to link Cork to the tourist town of Blarney with its historic castle. The supporters of the schemes also aimed to provide improved transport for passengers, livestock and farm produce between the farming area north-west of Cork and the city, and for coal and minerals in the reverse direction In 1887, Robert Worthington was awarded the contract for the near thirteen kilometre stretch, which was successfully opened as well in the same year.

A year later in 1888, the section to Coachford was added along with a line to Donoughmore in 1893. The Cork terminus was located at Bishop’s Marsh, now the site of Jury’s Hotel on the Western Road. The line crossed the South Channel via a small bridge leading to Western Road. The first four miles of the line were very like that of a tramway. The terminus was simple in nature, a single-storey building covered by a corrugated iron roof with a long platform. The iron engine and carriage shed spanned three tracks.

Known also as the Blarney Tram or the Muskerry Tram, the Cork & Muskerry Light Railway was financially successful and attracted much local use. Over its period of operation, the carriages and engines for the company were manufactured by three companies; Falcon Engine and Car Company of Loughborough, Perott’s iron Foundry, and Robert Merrick’s foundry on Warren Place (now Parnell Place).

In the 1920s, the line began to lose passengers to the Southern Motorways Omnibus Company who began to operate buses on the Western Road. The advent of motor vehicles also led to its demise and on 29 December 1934, the line was eventually closed.

The Bishop’s Marsh terminus is now occupied by The River Lee Hotel. However, the piers of the bridge spanning the south channel of the River Lee just west of Jury’s Hotel are still present and in their original position.

Kent Station:

Kent Station was originally built to replace the Dublin and Cobh termini, which were situated at Penrose Quay and Summerhill respectively. The deteriorating conditions of both these stations along with an increase in the use of trains by people in the city meant that a new more elaborate train station would have to be built.

Hence, in the early 1880s, it was proposed by the leading railway company in Cork City, the Great Southern and Western Railway, to construct Kent Station. Originally, the plan was to have trains running right through Kent Station or as it was known the Glanmire Road Rail Terminus and not have it as a terminal but in the course of time, all passenger trains using the station either started or ended there.

Building began in the late 1880s when the present day railway engine shed was built. Next, the coal gantry line was built and the goods warehouse already situated on the proposed station site was turned around to face east instead of north and additional tracks were also laid in the new goods yard. By 1890, the marshy land at the back of the houses on the Lower Glanmire Road overlooking the River Lee was filled in. In the spring of 1891, the real construction work began on the main building of the station.

The contractor was a Mr Samuel Hill, who was a native of Cork City. The architecture chosen for the station was basic and plain, primarily comprising ruabon brick faced with limestone. Two years later, this work was completed and the station was opened in February 1893, adjacent to the railway tunnel constructed under Blackpool. The local newspaper, The Cork Constitution reported the event on the morning after the opening;

” Yesterday the new Cork Passenger of the G. S. & W.R. was opened to traffic (at a final cost of £60,000 ) with the departure of the 6 a.m. train to Dublin. The last train had arrived in Summerhill around midnight, and at Penrose Quay at 2 a.m. and both these stations are now closed to regular traffic “.

The main building after construction was approximately 100 metres in length and various shops were built along with a booking area. Today this area is more noted for the ornate steam engine, which is on display. This is the oldest engine, the Number 36 on indoor display in Ireland. Another covered building was constructed at a right angle to the main edifices in which are two further platforms and an inclined subway. These are present today. In this area are offices, which can be seen a fabulous collection of rail line insignia or crests from around the world.

A large mural by artist Marshall Hutson is also on display. The mural depicts an old Hibernia Locomotive, working the first commuter line in the world, which served Dublin and Kingstown – present day Dun Laoghaire.

One of Kent Station’s famous events in the late twentieth century occurred in the 1970s, when the name ‘Kent’ was changed to “Folkstone Harbour”. This was due to the fact that a major part of the film, “The Great Train Robbery” starring Sean Connery and Lesley Anne Downes, was filmed at the station. The scenes were set in the 1850s and told the story of a train heist.

Kent Station was chosen as a film location to the fact that the station possessed an old world air, which was ideal for showing the sense of time and especially since the structure of the station has not changed since 1893.

Read more and Explore more: 6. Cork, The International City, c.1900 | Cork Heritage