The Norwegian presence in Corcach Mór na Mumhan was interrupted by invaders from Denmark circa 914 A.D. who also attacked other Viking towns in Ireland and gained control of them. In Cork, these new invaders – the Danish Vikings – started off by raiding the monastery on the hillside but soon turned their attention to wealthier and more powerful Gaelic kingdoms in Munster.

The Danes decided to settle in Ireland. They took over and adapted existing Norwegian bases and constructed additional ones to a similar but larger design. Unfortunately, the information available regarding a Danish settlement at Cork is historically and archaeologically deficient compared to that arising from excavations in Waterford and Dublin. Nevertheless, there are some clues that give an insight into the location, structure and society of Danish Viking Age Cork.

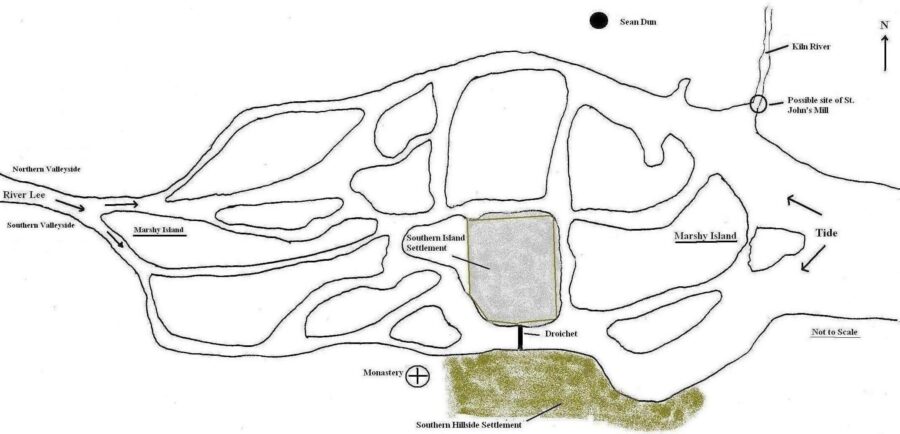

It is known that there were at least three main areas of settlement: firstly, they lived on the southern valley side next to the monastery, the core area of which is present-day Barrack Street; secondly, they settled on a marshy island now the location of South Main Street, the Beamish and Crawford Brewery, Hanover Street and Bishop Lucey Park; and thirdly they settled on the adjacent northern valleyside, now the area of John Street in Lower Blackpool.

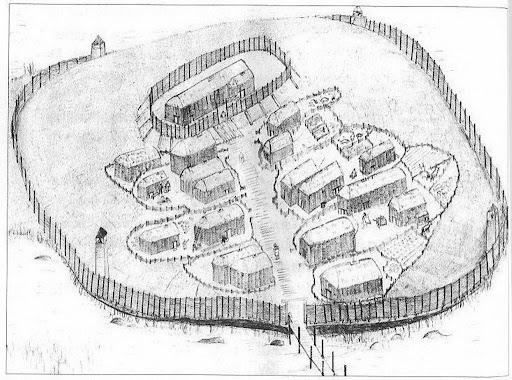

The second habitation zone was located on an adjacent marshy island, an area now occupied by the former Beamish and Crawford Brewery, South Main Street, Hanover Street and Bishop Lucey Park. An enclosing fortification of either timber or stone encompassed the settlement, and the entrance comprised a timber bridge called Droichet, similar to the Irish derivation droichead, meaning bridge. In Viking times Droichet would have linked the second Viking habitation on the island to the first habitation zone on the southern hillside. South Gate bridge now marks the spot of Droichet.

The publication Archaeological Excavations at South Main Street 2003-2005 (Brett & Hurley, 2014) records Hiberno Norse structures found under South Main Street area at the South Main Street and former Sir Henry’s Nightclub site. On trowelling back the earth, the archaeologists pealed back different temporal contexts. Two to three metres underneath our present day city, they exposed the remains of timber structures lingering, intrusive and protruding through the mud. There is an indication from the dendrochronological dates of the timbers found on the sites that there was a continuous felling of trees and construction of buildings and reclamation structures from just a few years before 1100AD to 1160AD.

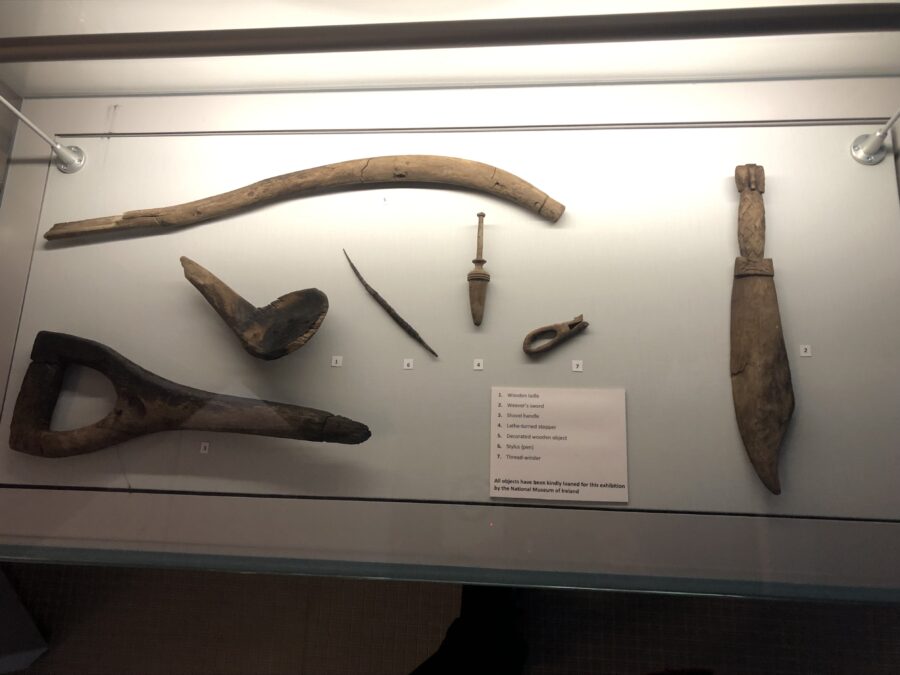

In 2017, archaeological discoveries made on the former Beamish and Crawford Brewery site uncovered the remains of a 12th-century church and a home dating to 1,070 AD along with other small wooden items such as a weaver’s yew wooden sword. In addition, intact ground plans of 19 Viking houses, remnants of central hearths and bedding material were unearthed.

So here on a swamp 900 years ago, a group of settlers decided to make a real go at planning, building, reconstructing and maintaining a mini town of wood on a sinking reed ridden and wet riverine and tidal space.

To obtain an overview of what the Viking settlement may have been like for its citizens, we must combine information from finds in Cork with evidence retrieved at excavations in Waterford and Dublin. The settlement on the island had a central routeway on a north-south axis. Property plots, laneways, outhouses, storage pits would have run at right angles to the routeway itself. Houses within the settlement would have been small and basic, comprising one large room and a maximum of two other rooms. They would have been made of timber or wattle and daub with thatched roofs, which meant there was always a risk of fire.

The first houses built in Cork were of a type recognised by archaeologists as Hiberno-Norse (Viking Age) Type 1. The houses built in Cork for the first 50 years or so of the settlement (1070AD-1130AD) had an identical ground plan to the Type 1 houses of Dublin, Wexford and Waterford and every feature in the Cork houses is paralleled in these towns and therefore the early buildings of Cork were clearly within the mainstream Of Hiberno-Norse culture.

Life in the town would have been harsh. Although no skeletal remains have yet been found in any of the three primary habitation zones, evidence from other sites indicates that the lifespan would have been short, with most people living no longer than thirty to forty years. In Cork, the mortality rate would have been influenced by overcrowding, inadequate waste disposal and the effects of living on damp, marshy land. The presence of rubbish would have attracted rats, while the smoke from the household fires would have polluted the air. Infectious diseases such as influenza and tuberculosis would have been rife.

The third habitation zone was situated on the northern valleyside, primarily around present-day Lower Blackpool, through which the Kiln River flows before joining the northern channel of the River Lee, directly across from Cork Opera House. The origin of the name Kiln River is unknown, but its waters comprise three main streams: the Glen River, the Kilnap River and the Bride River. The name ‘Kiln’ is used to describe the meeting of these three rivers at Blackpool. It is known that a Viking water mill, St. John’s Mill, was located on the Kiln River. In the 1920s work on John Street revealed an inscribed stone with the inscription: St. John’s Mill 1020 A.D.

In 1844, just north of this site at Kilbarry in upper Blackpool, a Viking Age hoard was discovered accidentally by Denis Murray during farming operations. In May of that year, Murray’s find was displayed at the meeting of a Cuverian Society, an upper-class antiquarian club, which reported that the hoard consisted of approximately fifty silver rings in a wooden box. Burying hoards of silver was common practice during Viking times.

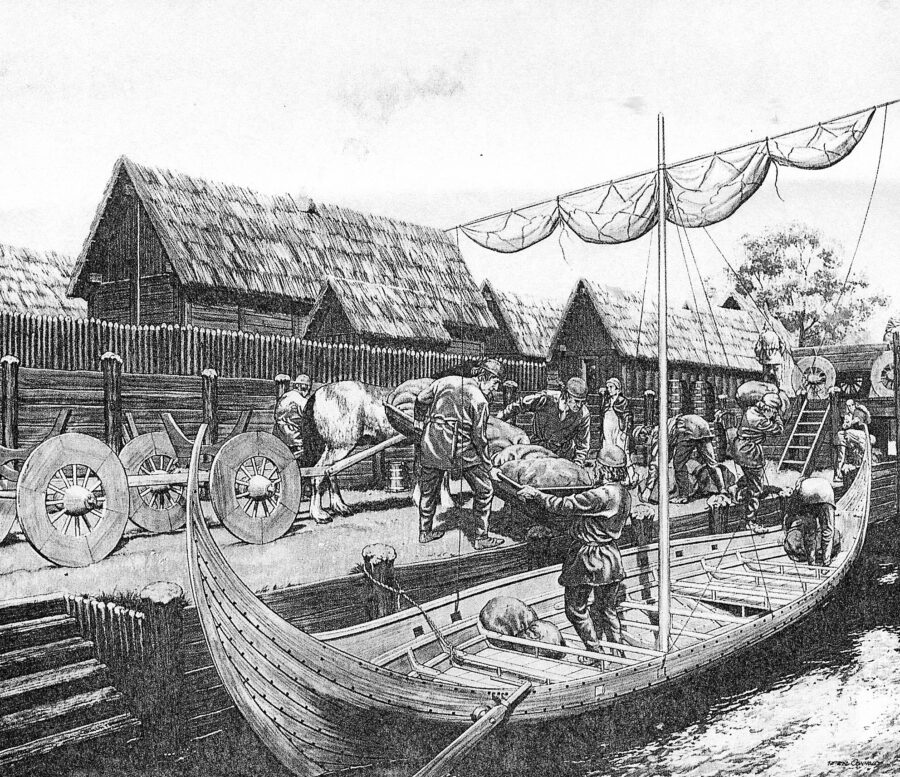

It is known that trading took place in the Danish Viking settlement. The monks in the adjacent monastery recorded in their annals that once could get a boat from Cork to mainland Europe. Goods such as wine and salt comprised the main imported commodities. Wine would have been imported for church use while salt would have been imported for the preservation of meat. The exact source of these commodities is unknown; remaining documentary evidence suggests that the trading network reached across to Britain and France. In terms of exports, it is likely that the principle exports were sheep’s wool, hides and meat from cattle and fish from the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea. It is also possible that perhaps an internal trading system was set up between the Cork Viking port and other the Danish Viking ports at Youghal and Kinsale.

We also know that trade was conducted with the monastery and also with local Gaelic families, with whom the Vikings had made alliances. It is unfortunate that much of the surviving documentation does not give a detailed account of the relationship between the natives and the foreigners. Adjacent to the Viking settlement on the northern valleyside was a Gaelic Irish ringfort settlement called Sean Dún (later anglicized as Shandon).

The McCarthy clan owned this and they also had strong territorial claims throughout counties Cork and Kerry. Sean Dún, which means ‘old fort’, was one of a number of fortifications on the clan’s land. The main historical evidence for this area comes from Cormac McCarthy’s Vetus Castellarium, which dates between 1128 and 1131 and describes the system of power-sharing, especially equal trading rights, which existed between the McCarthys and the Vikings.

Read more: Newspaper column write-ups and interviews with archaeologists:

26 September 2017, RTE, 1,000-year-old Viking sword discovered in Cork city, Consultant Archaeologist Dr Maurice Hurley said it was one of several artefacts of exceptional significance unearthed during recent excavations at the South Main Street site, along with intact ground plans of 19 Viking houses, remnants of central hearths and bedding material”, 1,000-year-old Viking sword discovered in Cork city

24 May 2018, Irish Examiner, Viking artefacts indicate industrious life within Cork city; “While many of the artefacts taken from the ground below Cork’s former Beamish & Crawford brewery site in the inner city look like the possessions of dignitaries, the rich decorations instead reflect the craftwork of those who lived there nearly 1,000 years ago”. Viking artefacts indicate industrious life within Cork city

4 April 2022, Irish Examiner, Cork In 50 Artworks, No 48: The Viking Weaver’s Sword, found at the Beamish site. “The Weaver’s Sword is a Viking artefact, believed to date to the late 11th century, that was discovered in the course of an archaeological dig at the Beamish & Crawford site in Cork city in the spring of 2017”. Cork In 50 Artworks, No 48: The Viking Weaver’s Sword, found at the Beamish site

20 August 2023, The Echo, Archaeologist provides insight into lives of first Corkonians, “According to Dr Rebecca Boyd, who has analysed materials uncovered in archaeological works carried out in the South Main Street area in 2003/4, the data tells “precious stories” and gives “glimpses of daily life in Cork 1,000 years ago”. Archaeologist provides insight into lives of first Corkonians

Read More: Archaeology & Development – Cork City Council, Archaeology & Development – Cork City Council

Publication: Archaeological Excavations at South Main Street 2003-2005:

This is the eight book on the archaeology and history of Cork to be published by Cork City Council. This publication outlines the results of two large-scale excavations which took place at 36-39 and 40-48 South Main Street. Both sites are located in close proximity to the South Gate Bridge, one of the main entrances to the medieval walled city of Cork.

The excavations were undertaken by Sheila Lane and Associates and the Department of Archaeology, UCC. Cork City Council. With the financial support of the Heritage Council and in partnership with the Department of Archaeology, Cork City Council through the City Archaeologist undertook to publish the reports.

It is co-edited by Dr Maurice F Hurley and Ciara Brett, City Archaeologist, Cork City Council. The publication is available directly from the City Archaeologist Ciara Brett (ciara_brett@corkcity.ie) or read it in Local Studies, Cork City Library, Grand Parade, Cork.

Read more and Explore more: 2a. Anglo-Normans and the Medieval Town | Cork Heritage