Regional Conflicts:

At the beginning of the 1500s, the English Crown did not have much power in Ireland. Rebellions during the previous centuries had been so successful that by the time King Henry VIII attained the throne in 1509, it is recorded that the native Irish chiefs held almost all of Ulster, three-quarters of Connacht, the midlands of Meath and Leinster, part of the east coast between Dublin and Wexford and north and west Munster. In the Cork area, the McCarthy clan, whose lands had been taken by the Anglo-Normans in the 1170s, had managed to regain a substantial amount of their territory.

In Munster, fighting was common as the Native Irish clashed with descendants of Anglo-Norman families, such as the Desmonds and the Ormonds, over land. Indeed, so strong were these local conflicts that royal power in England was often forgotten about. In addition, such was the prosperity of the walled town of Cork that, in truth, the settlement could be described as an independent, self-governing republic. This situation also existed in walled towns such as Limerick, Waterford and Galway.

The accession of King Henry VIII to the throne was to change many aspects of Anglo-Irish relations. A royal survey commissioned in 1515 revealed that in several counties bribes were being paid to Irish chieftains to buy their good will. For example, the citizens of Cork were paying the McCarthy chieftain forty pounds a years for immunity from attack. It was also revealed that many English settlers had integrated alarmingly well into Irish culture. In some instances, they were going so far as to make peace with the Irish without the prior permission of the King. This report called for radical political change.

Reformation:

The subsequent reforms included the forcible introduction of a new religion – the Church of England. The first effects of the Reformation were felt in Cork in the 1540s when the abbeys of the Franciscans, Augustinians and Dominicans were forced to close. The monasteries’ possessions were confiscated and redistributed among the wealthy supporters of the Crown. In response there were rebellions throughout the country, which continued during the subsequent reigns of Henry VIII’s Protestant son Edward and his Catholic daughter Mary.

During Edward’s reign, English power declined further, but the reign of Queen Mary brought hope for the Catholic population. This hope faded rapidly after 1558 when she died and Elizabeth, her Protestant step-sister, became queen. Elizabeth I spent the first year of her reign re-examining the state of affairs in England and Ireland before re-establishing the Church of England. She brought back her father’s Act of Supremacy – a strong policy of colonial control – and subsequently enacted several other regulations to increase the monarchy’s jurisdiction in Ireland. However, her laws succeeded only in those areas where English dominance was strongest, such as Dublin and The Pale, while elsewhere the Irish chiefs continued to hold sway.

To counteract this, Elizabeth initiated the ‘Plantation’ concept, sending English farmers to live and work on Irish land. In places such as Cork, pardons and financial compromises were offered to powerful clans, such as the O’Sullivans and the McCarthys, to persuade them to accept this new set of rules. The Catholic clergy, however, were immune to such promises. Neither bribery nor the severest punishments could make them conform, and Catholicism continued to practised openly. The worsening situation in Ireland was compounded by England’s war with the Catholic King of Spain, Philip II.

The Spanish Armada & Cork:

The discovery of the Americas quickened the Empire’s thirst for power, especially through trading links. England and Spain were vying for control of the maritime trading routes. The tension between the two escalated in July 1588 when the first of several planned Spanish expeditions set sail to invade England. The Spanish Armada was the largest naval force ever seen. When the huge fleet came into view of England’s coast, Elizabeth sent her best admiral, Sir Francis Drake, to repel the Spanish. Using clever tactical manoeuvres, the English gained the upper hand. During the ensuing battle, Sir Francis Drake’s five ships of war were pursued into Cork Harbour by the Spanish. The English sailed up the Carrigaline River and anchored under Currabinny Hill. The Spaniards entered the river in pursuit, but failed to find them and sailed out again. The placename Drake’s Pool marks Drakes’s safe hiding place.

In 1580, Sir Walter Raleigh, famous English sailor and explorer arrived in Cork at the behest of the Queen to suppress any disloyalty, as the English feared that the Spaniards might launch another attack and use Ireland as a ‘backdoor to England’. Spending much time in Munster, in particular on his estate in Youghal, Raleigh made regular visits to the Youghal town and Cork.

New Fortifications:

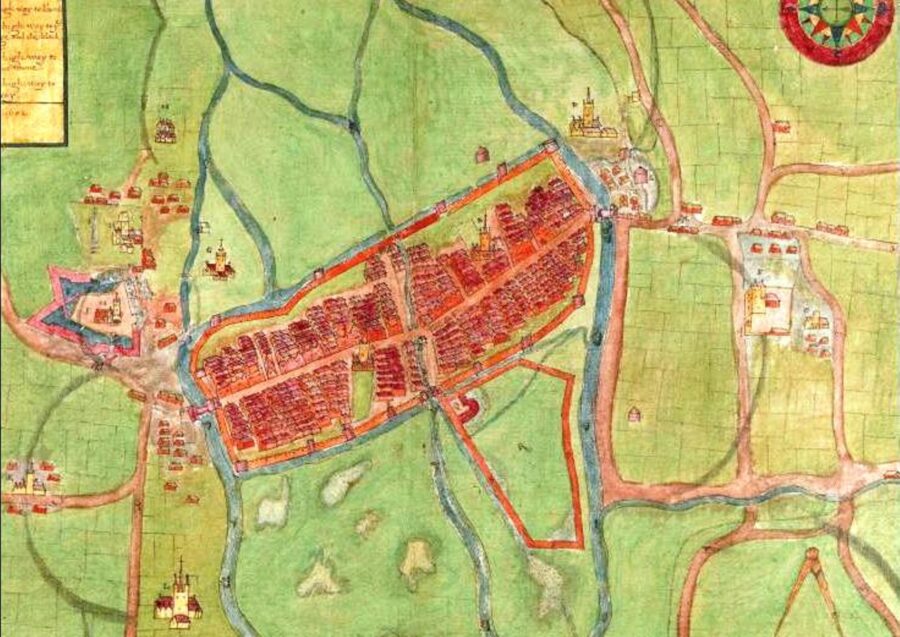

To protect the town walls from attack, two fortifications were constructed: Blackrock Castle and Elizabeth Fort. Blackrock Castle was built in 1582 by the citizens of Cork and has been restructured twice, in 1722 and 1827. In recent times, Blackrock Castle has been purchased by Cork City Council and is awaiting redevelopment. In the case of Elizabeth Fort, an order was given by Elizabeth I in January 1590 to create new fortifications in each major coastal walled town, in particular Waterford, Limerick, Galway and Cork. Accordingly, in 1601 an earthen embanked fort was constructed to accommodate an English garrison, and was named in honour of the queen.

As well as these new fortifications, Shandon Castle stood overlooking the main northern approach road known as Mallow Lane, now Shandon Street. In 1177 the castle had been the stronghold of Diarmuid McCarthy, but was taken over by the Anglo-Normans. It passed through a number of hands, but in the early 1500s was owned by the Barry family. The Pacata Hibernia (c.1585-1600) depicts the castle as having two large towers adjoined to each other, one being larger than the other.

Culture and Edmond Spencer:

Despite the many insurgencies and political machinations, sixteenth-century Cork was also a place of culture and genteel pursuits. For the wealthy, there were many pleasurable diversions, such as reading and hunting. The city also enjoyed the presence of famous personages, most notably the eminent poet Edmund Spencer, who spent nineteen years in Cork His residence was the Castle of Kilcolman near Doneraile in North Cork. In 1580, Spencer was appointed secretary to Lord Grey, the Lord Deputy of Ireland. In 1595*, Edmund married Elizabeth Boyle, a relative of the first English Lord Cork, in the medieval church of St. FinBarre. It was also whilst Spencer settled in Cork that he wrote his famous poem, ‘The Faerie Queen’. On 30 September 1598, Spenser was named Sheriff of the County of Cork. His duties included acting as adviser to the Lord Deputy and collecting rents from tenants of the Crown in County Cork.

Read more and Explore more: 3b. Seventeenth Century Cork | Cork Heritage