Society:

The population of Cork c.1300 is estimated at 800 people with the main language of the law being English. It is likely that wealthy Anglo-Norman families of the merchant class were the principal residents as they would have been able to afford the rents payable to the King.

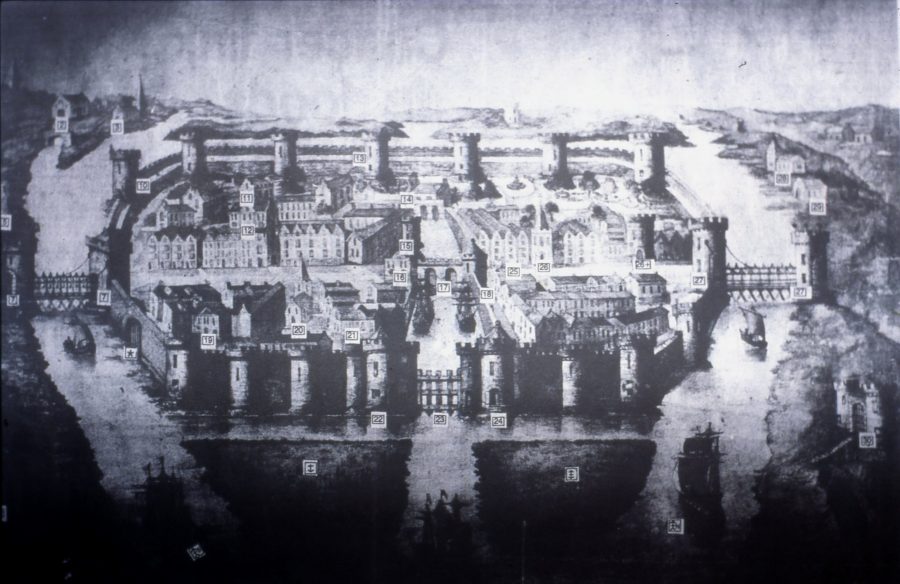

Some of these wealthy merchants founded the Corporation of Cork, a municipal, legal, and administrative body; it is unknown when it was formed or how many members it had. The Corporation controlled the town’s financial affairs and aimed to create a vibrant mercantile economy in the town, ensuring that all associated taxes were paid. It was also responsible for upholding the laws of the town and paying a watchman to supervise after the towns’ defences and streets. Much of the Corporation’s public business was conducted just off South Main Street, in the area now occupied by the former Beamish and Crawford Brewery. The council tower, armoury, the court house, commandant’s house and the treasury were all located nearby.

Mercantile Families:

The families involved in the government of the town included the Roches, Skiddys, Galways, Coppingers, Meades, Goulds, Tirrys, Sarfields, and the Morroghs. These surnames comprised the mayoral list from the early thirteenth century until the seventeenth century: forty mayoral titles in the Galway name are recorded between 1430 and 1632; thirty-six Skiddys between 1364 and 1624; and twenty-nine Goulds. These families also controlled large portions of Cork’s trade and owned land which they rented out to less fortunate merchants.

From the fourteenth century to the sixteenth century, the majority of the houses overlooked the main streets. Extending perpendicular to North and South Main Streets were numerous narrow laneways, which provided access to the burgage plots of the dwellings. Comprised of individual and equal units of property, burgage plots extended from the main street to the town wall and their size was carefully regulated by owners and tenants.

Housing:

Several archaeological excavations have revealed evidence for the construction of different types of houses within the walled town. The remains of thirteenth and fourteenth-century Anglo-Norman houses comprised post-and-wattle houses and sill-beam houses. For the first 300 years of the walled town’s history, it was illegal to leave a fire lighting at night – a misdemeanour punishable by a heavy fine, known as ‘smoke silver’.

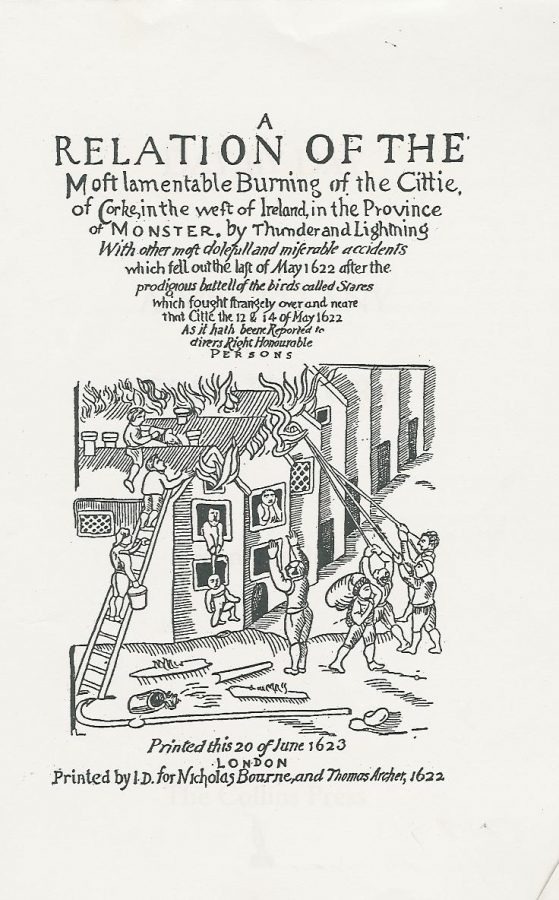

Indeed, the building of timber houses within the town was condemned in May 1622 when on the last day of this month, a large fire swept through a large portion of the town. It was not, however, caused by mismanagement of domestic fires but by lightning striking one of the timber houses on North Main Street.

Contemporary descriptions in the Council Books of the Corporation of Cork detail that 1,500 houses were burnt down and that the northwest and southeast parts of the town were destroyed. A contemporary account by an unknown author describes how the inhabitants saw a ‘dreadful lightning with flames of fire break out of the clouds and fall upon the cittie at the same instant at the east and the highest part of the cittie .. there the fire began with horrible flames.’

Daily Life:

Despite the wealth of the town, daily life in Medieval Cork would have been difficult. Overcrowding was common in poorly ventilated dwellings, whilst the water supply was subject to contamination from sewerage and improper rubbish disposal. Household waste was thrown onto the streets and laneways and dead animals were left to decay where they fell. The upper-floor of the residences usually projected out into the street, blocking out the light and lending the town a gloomy aspect.

The streets were poorly paved and very muddy due to tidal water seeping up through the marshy ground. The air would have been damp and heavy, and as a result many diseases were rampant, including; measles, mumps, influenza, leprosy, chicken pox, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, typhus and whooping cough. Inadequate personal hygiene would also have meant that fleas lice were common.

WATCH: A short now and then film based on the model of the Walled Town of Cork by Kieran.

Mortality:

The mortality rate was low: one-fifth of all babies died before their first birthday. Those who survived past the age of one had a 50% chance of surviving to adulthood, but most children died before their tenth birthday. All this death and misery was compounded in the mid-1300s when the Black Death swept through the town and its liberties. The hard lives and premature deaths of the inhabitants have been confirmed by a find at Crosses Green of over 200 skeletons.

Under the careful excavation of Catyrn Power, the majority of the graves were discovered within the boundaries of buildings especially within the church and cloister area. Since, the abbey was built on a marshy island, there was a lack of acid in the underlining soil which resulted in little deterioration of the bones of skeletons found. All were reburied appropriately and safely. The majority were excellently preserved and therefore most of the graves comprised of intact comprehensible skeletons.

Three-quarters of the individuals were found to be adults, mostly aged in their twenties. Just less than half were found to have degenerative joint diseases or some form of arthritis, and in several nutritional deficiencies, tumours and dental diseases were noted.

Learn more about the work of Catyrn Power, Archaeologist, here: The Skeletons in my Cupboard by Catryn Power. Lecture 101. for TRASNA NA TIRE | CORK ARCHAEOLOGIST Catryn Power

Crime:

The levels of poverty and misery meant that crime was a serious crime. Punishments in medieval times were severe, with the death penalty automatically given for serious crimes. Execution was usually by beheading or hanging. Up until the late 1800s, public hangings took place at Gallows Green, near the southern road leading into town. The site is now marked by Greenmount National School and the Lough Community Centre. In 1990 a mass grave was discovered in this area containing the remains of at least fifteen individuals. All the bones were disarticulated, many were broken and in most cases they were stacked into neat piles with the skulls lying close by.

Religious Orders:

It is often the case that poverty goes hand in hand with religious devotion, and Cork was no exception. Religion played a huge role in the lives of the citizens – a fact supported by the number of religious buildings the town was willing to finance. Indeed, from the mid-sixteenth to the late seventeenth century, the influx of new religions, especially Protestanism, proved contentious.

There were two parishes within the walled area, one encompassing North Main Street and the other South Main Street. Christ Church, rebuilt in 1720, was located off South Main Street, now the Cork Archive Institute. Overlooking North Main Street was St. Peter’s Church, which in recent times has been adapted as the Cork Vision Centre. Both were Christian until the sixteenth century when they were converted for a Protestant congregation.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a number of religious foundations were established in the suburbs. From the earliest times of their conquest, the Anglo-Normans had been interested in exercising control over the Christian Church. The realisation that the Church owned large tracts of land meant many of the clergy soon became indirectly associated with the conquest. Wherever a new Anglo-Norman colony was established, especially in urban areas, the foundation of new religious houses came soon after. In Cork, at least five new religious houses and three hospitals were founded during the twelfth and thirteenth century.

The Franciscans, who established an abbey (1229) in the area of the present-day North Mall, owned large tracts of land on the northern valleyside, while on the southern valley side, the main religious orders included the Benedictines (c.1230), Dominicans (1229) and the Augustinians (c.1270).