Trail starts at Port of Cork Building.

Below is a brief historical walking trail, which covers some of the topics on my physical walking tour. The information is abstracted from various articles from my Our City, Our Town column in the Cork Independent, 1999-present day, Cork Independent Our City, Our Town Articles | Cork Heritage

Introduction:

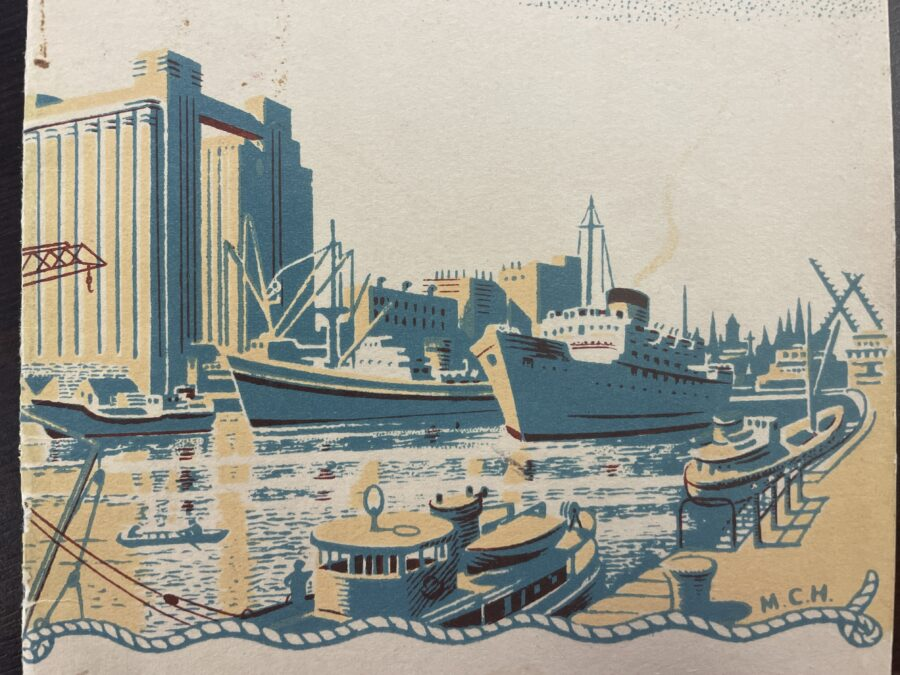

Through its docks, Cork was connected to the outside world – the international and small town – ambitious in its ventures linked to a world of adventure and exploration. The timber quays kept back the world of the tide, for reclamation in the city was still taking place as Cork people sought to bring the city centre to a new place of being.

Cork City though has always strived to be a new place. It has always been ambitious in its endeavours. The city has come so far, but it is also that past that anchors the Corkonian identity in the present day.

Change abounds at Cork’s docks in the present day as more and more of the services of the Port of Cork move to the new Port of Cork terminal in Ringaskiddy.

Watch a great video on Cork by Jason Keane – the city and harbour in miniature, the film maker has a great eye for detail, click on play below:

The Early Historic Docks of Cork:

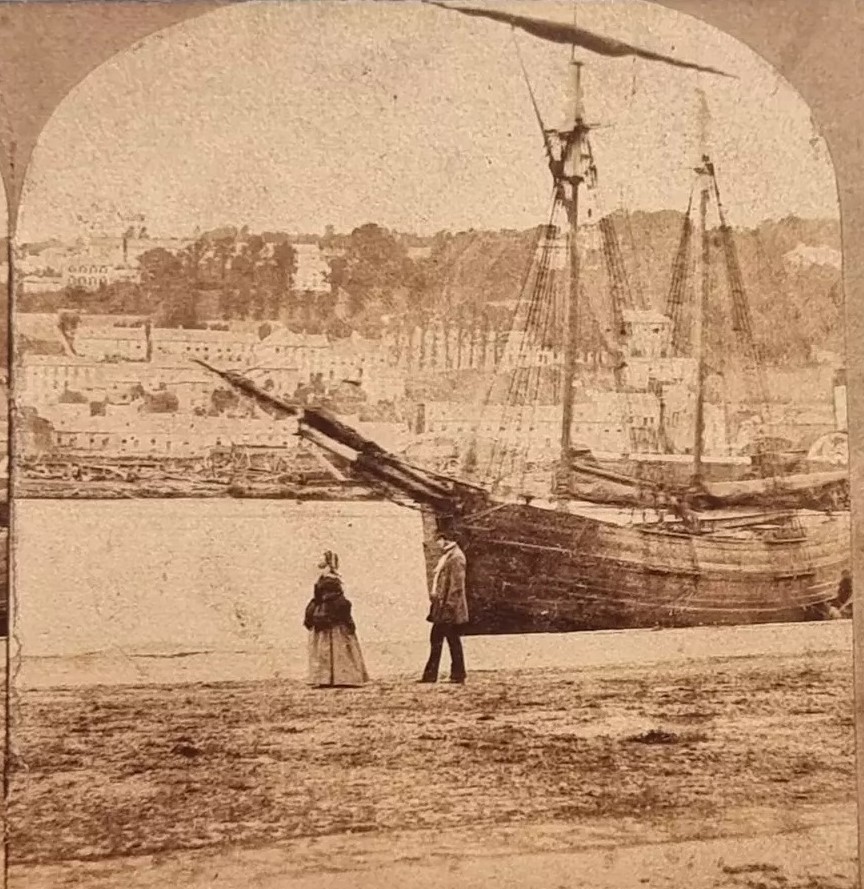

Ever since Viking age time over 1,000 years ago, boats of all different shapes and sizes have been coming in and out of Cork’s riverine and harbour region continuing a very long legacy of trade. Port trade was the engine in Cork’s development.

Two hundred years ago, considerable tonnage could navigate the North Channel, as far as St. Patrick’s Bridge, and on the South Channel as far as Parliament Bridge. St Patrick’s Bridge and Merchants’ Quay were the busiest areas, being almost lined daily with shipping. Near the extremity of the former on Penrose Quay was situated the splendid building of the Cork Steamship Company, whose boats loaded and discharged their alongside the quay.

In the late 1800s, the port of Cork was the leading commercial port of Ireland. The export of pickled pork, bacon, butter, corn, porter, and spirits was considerable. The manufactures of the city were brewing, distilling and coach-building, which were all carried on extensively. There were many large establishments in the timber trade, also many in which salt provisions were cured, and several tanneries, which produced leather of the choicest quality. There were also some salt, lime and chemical works.

The imports in the late nineteenth century consisted of maize and wheat from various ports of Europe and America; timber, from Canada and the Baltic; fish, from Newfoundland and Labrador regions. Bark, valonia, shumac, brimstone, sweet oil, raisins, currants, lemons, oranges and other fruit, wine, salt, marble were imported from the Mediterranean; tallow, hemp, flaxseed from St. Petersburg, Rig and Archangel; sugar from the West Indies; tea from China and coal and slate from Wales. Of the latter, corn and timber were imported in large numbers. Exports were principally pewter, whiskey, butter provisions, cattle, fowl, and eggs. Butter was the staple trade.

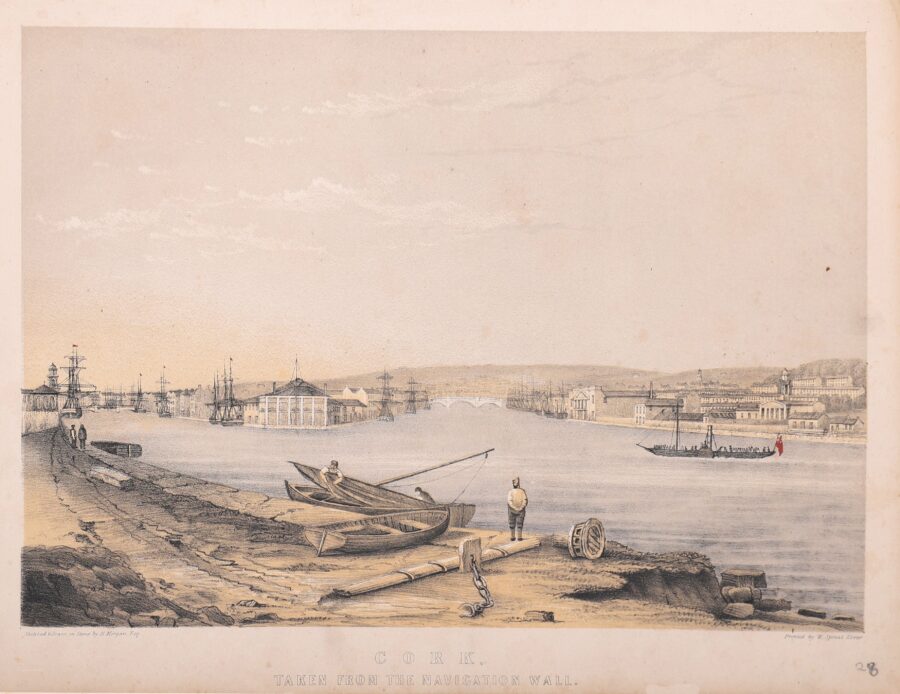

Mapping Cork’s South Docks, 1774-1852:

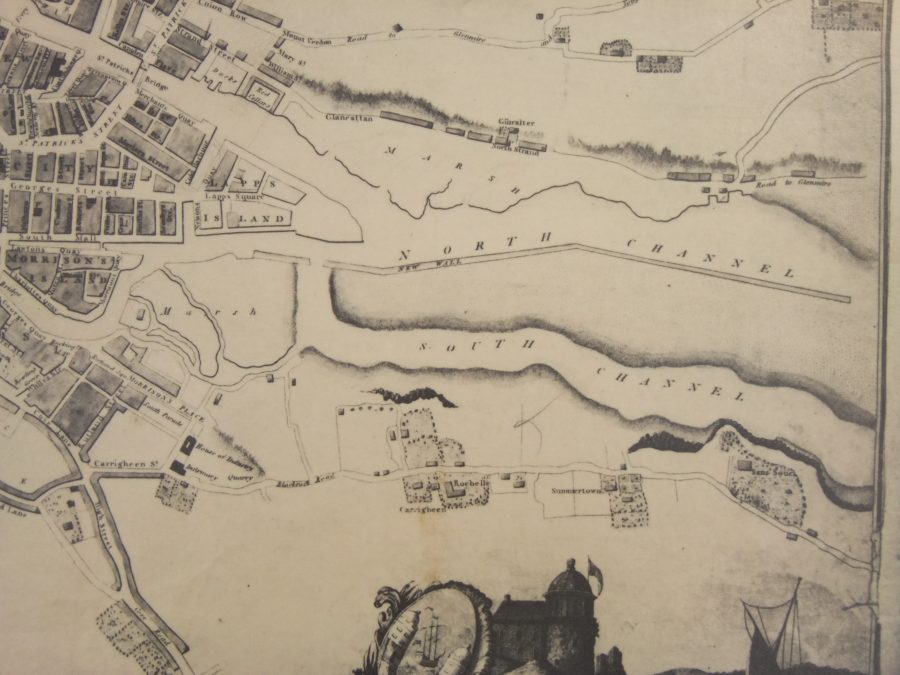

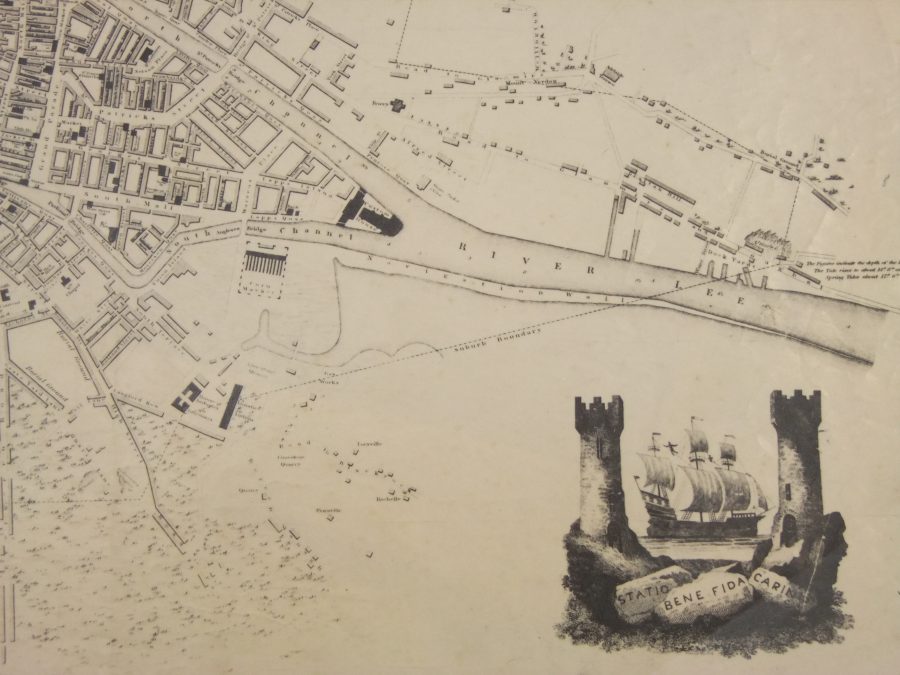

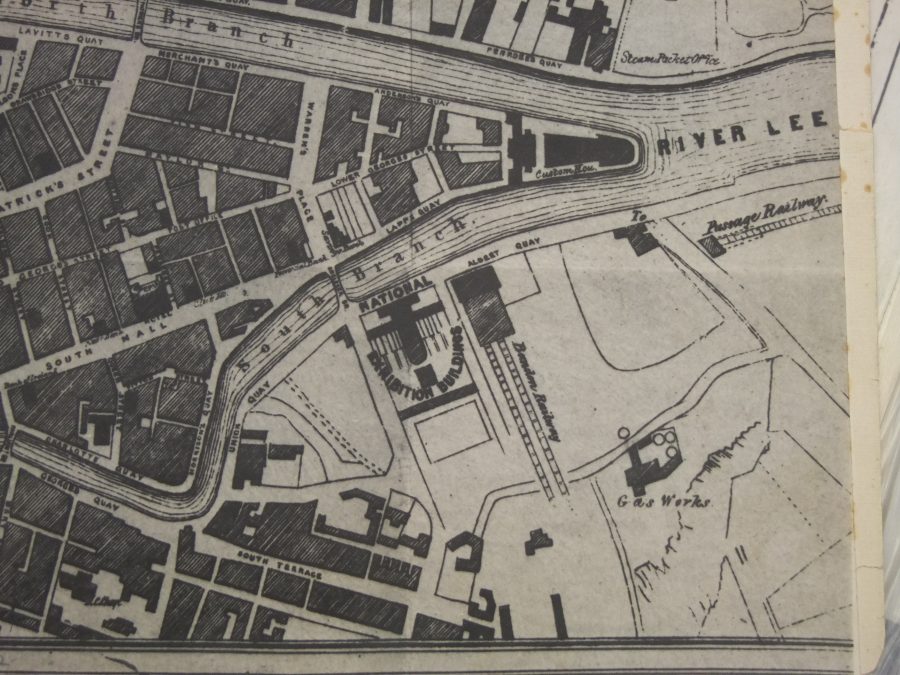

Up to the early nineteenth century, it would have been the Corporation of Cork, which managed the comings and goings of ships into the city centre’s complex of quays. The Corporation collected shipping taxes and supported the construction of bridges and public and private quaysides. Notable in earlier maps of the city are the quays depicted in the walled town of Cork and the myriad of quays constructed during the eighteenth century especially around the Custom House (now part of the Crawford Art Gallery) on the so called eastern marshes.

In early nineteenth century records, silting up of the River Lee estuary was a common problem. In 1820, Cork Harbour Commissioners were formally constituted and purchased a locally built dredger. The dredger deposited the silt from the river into wooden barges, which were then towed ashore. The silt was re-deposited behind the Navigation Wall. The Navigation Wall was completed in 1761 to be a guiding wall for ships entering into the city centre’s quays complex. During the Great Famine, deepening of the river created jobs for 1,000 men who worked on creating the Navigation Wall’s road. The road was later to become The Marina Walk.

The Old Port of Cork Building:

The Custom House and the Bonded Warehouses complex have a deep history. The archives of the Cork Harbour Commissioners survive in Cork City and County Archives and planning documents in Cork City Council contain history reports on the complex.

Buildings on Lapp’s Island are first noted in Murphy’s Map of Cork 1789.

In the Irish Architectural Archive, Dublin in the archives of builder William Deane, there are records for 1801-1802 describing that a temporary custom house and shed exists on Lapps’ Island. This was a move from the earlier eighteenth century custom house (now part of the Crawford Art Gallery).

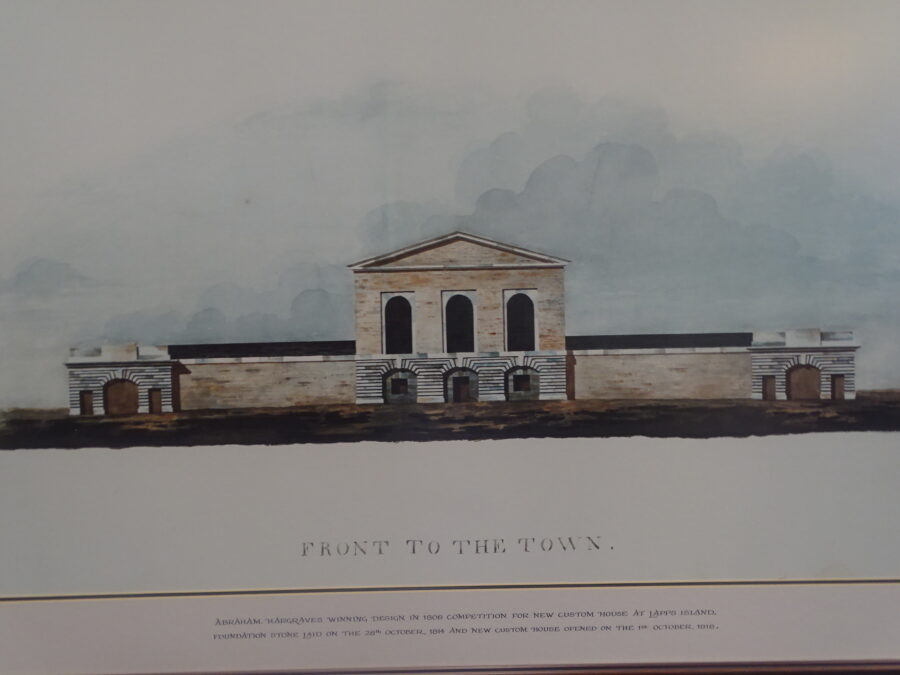

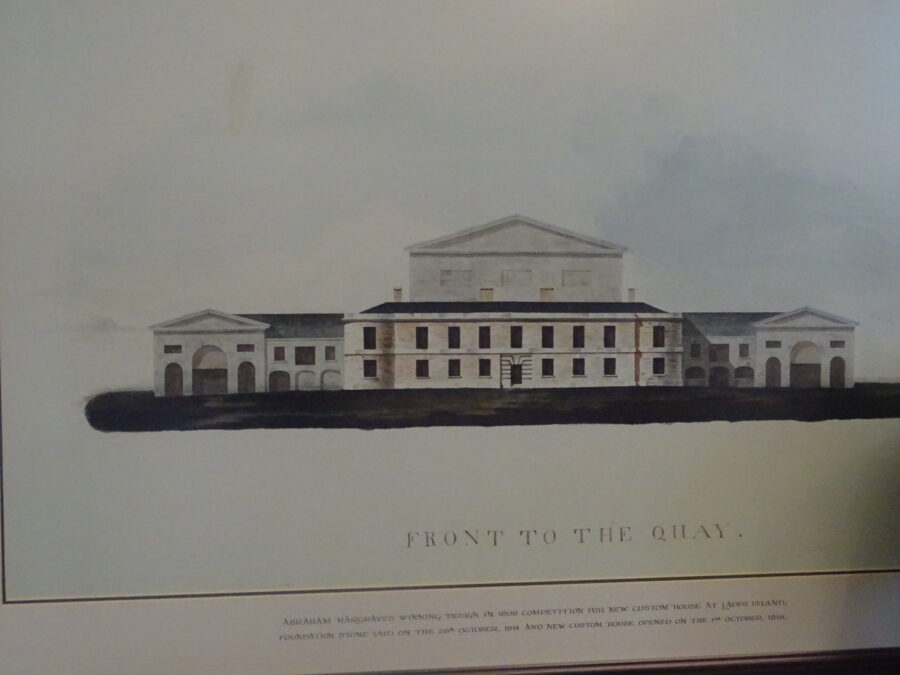

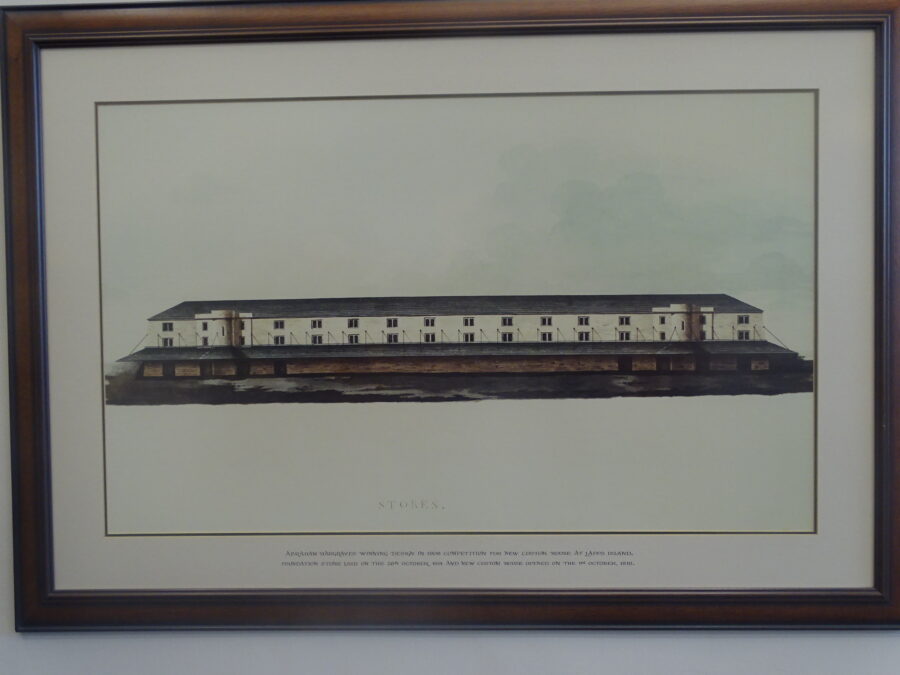

In 1808 there was competition for a larger custom house structure on the island. The architectural competition was won by Abraham Hargrave Junior. The proposal was for a central block with two adjoining wings, informed by Neoclassical design.

The principal façade was to face the city to the west with a three story block of stores facing the east.

The foundation stone was only laid in 1814. Tuckey’s Remembrancer (1837) records the event on 28 October 1814:

“The foundation stone of the custom-house on Lapp’s island, was this day laid by Robert Aldridge, esq. the collector of customs, who was attended by the officers of the several departments. A brass plate, with a suitable engraving, was placed under the stone, and Mr. Hargrave, junior. in the absence of his brother, the architect, presented a silver trowel to Mr. Aldridge, with an address. When the ceremony was concluded, Mr. Aldridge gave some bank notes, to be expended by the labourers in drinking the king’s health”.

In 1818, the construction of the custom-house complex was finished, and business began to be transacted in it, in the various revenue departments.

The Cork Harbour Commissioners were formed on 21 September 1814 and formally reconstituted under the Cork Harbour Act in 1820. Their principle aims were to improve ease of navigation, undertake dredging and repair and maintenance to the quays.

The original layout of Cork’s Custom House and the use of its various rooms changed over time due fluctuations in port trade.

In 1904-1906 a magnificently ornate boardroom with new offices, designed by William Price, the then Harbour Engineer, was added. They were built over the south wing in a new two story extension.

Towards the end of 2009, the Port of Cork implemented a Leisure and Recreation Strategy for Cork Harbour. The primary focus of the strategy was on water based Leisure and Recreation activities in and around Cork Harbour; “The Port of Cork aims to play a leading role in providing and supporting improvements of amenities in these areas. Consultation with community groups, water related clubs, statutory bodies and other interested parties will be an important feature of giving life to this strategy in the future”. In June 2010 the Port of Cork Marina Pontoon was opened.

In 2017 the Port of Cork sold the three-acre site in the city’s Custom House Quay to Tower Development Properties, a company formed by Kerry brothers Kevin and Donal O’Sullivan.

In March 2021 plans for a new 34-storey hotel tower were given the green light by An Bord Pleanála to the latter company as part of a redevelopment of Cork City’s Custom House Quay site. The current site awaits the start of this development project.

In April 2022, the Port’s container terminal opened at Ringaskiddy. It took four years to build. It cost €94m and was supported by a grant from the EU’s Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), in conjunction with bank financing. By December 2022, more than 90,000 containers were loaded and discharged at the Port of Cork Company’s (PoCC) new Cork Container Terminal (CCT) in Ringaskiddy.

The container terminal in Ringaskiddy, which is on a 39- hectare site, is operational 24/7, and is one of the largest deep-water multimodal berths in the world, at 13 metres deep and 360 metres long.

In July 2024, the Port confirmed it had secured a €38.4m EU grant from the EU’s Connecting Europe Facility (CEF).

In October 2024, a €99m financing deal was agreed to fund a major expansion of the Port of Cork’s facilities to help drive growth in the offshore renewable energy sector. The funding deal was with the Irish Strategic Investment Funds (ISIF) to add to the EU’s CEF grant.

The Port of Cork plans to sell off its sites in Tivoli and the Cork city quays for redevelopment, which is in line with the government’s Ireland 2040 plan for economic growth in Cork.

WATCH 2017 animation video on Port of Cork redevelopment at Ringaskiddy:

VIEW: Port of Cork opens €89m cargo terminal at Ringaskiddy, 23 September 2022

READ: The Port of Cork’s ambitions for 2050, The Port of Cork’s ambitions for 2050

READ: Port of Cork Masterplan 2050 – Port of Cork

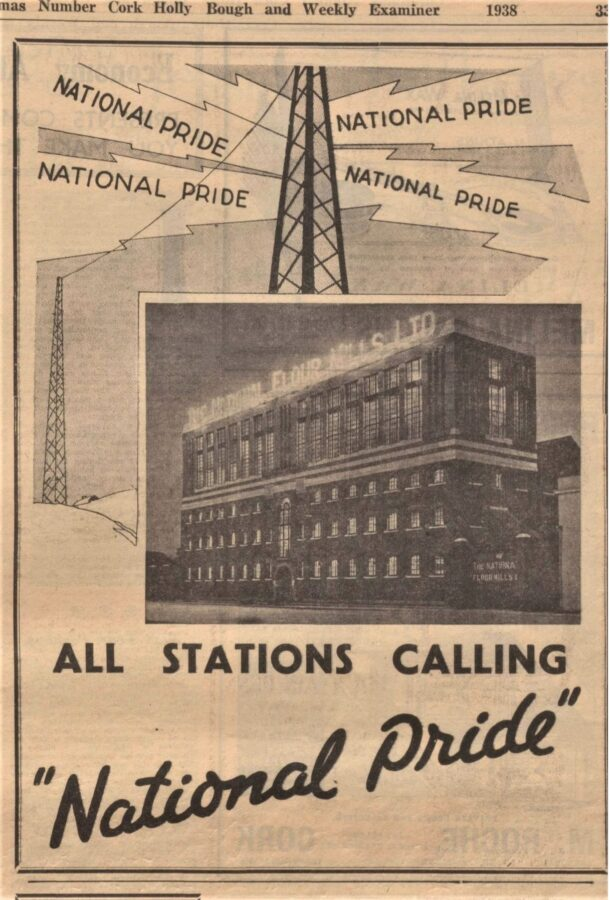

The Cork National Flour Mill Complex:

By 1810 Cork had become a big market for flour especially with brewers and distillers. The milling trade has passed through a complete revolution in the process of manufacture during the previous forty years. Up to the years 1875 to 1880 the only method of manufacturing flour was grinding by millstones, the wheat being ground between two flat circular stones.

Creating the Cork National Flour Mills: Between 1875 and 1880 Cork became one of the first milling centres in Ireland to adopt the roller process, and a number of well-equipped mills in the City and County were constructed, in which some 70,000 tons of wheat was milled annually, and in addition, close on 90,000 tons of maize was ground.

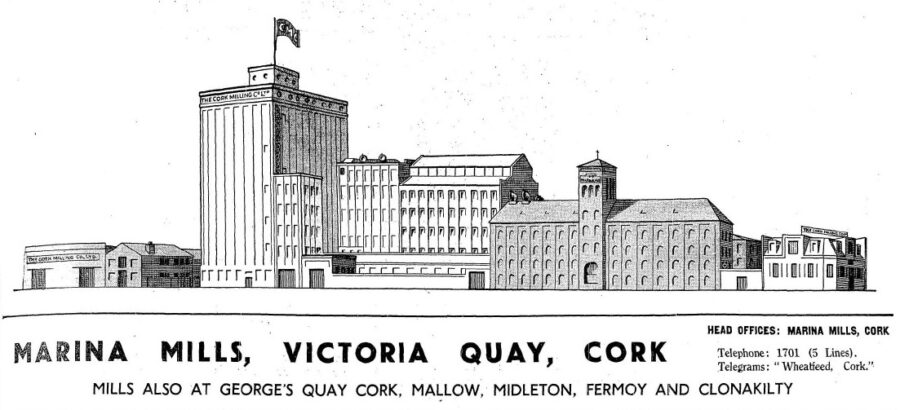

A large and landmark mill and warehouse complex known as the Cork National Flour Mills on Cork’s South Docks was built in 1892.

Since the construction of the original mill from 1892 to his death in 1936 Corkman Thomas J Fitzgibbon was mills manager of the National Flour Mills. The Cork Examiner on Thomas’ obituary on 21 December 1936 was previously connected with flour-milling all his life and coming of a Midleton family who was always engaged in this industry. He began his career with Messrs T Hallinan and Sons, millers, Midleton, and then joined Messrs Simons, an English firm of milling engineers. Whilst in their employment he superintended the erection of mills in many parts of the world, travelling extensively in the East. He later returned to his native county where he took up a responsible post with Messrs. J W McMullen and Sons George’s Quay Cork. On the inception of the National Flour Milling Company he planned the machinery for the new mills in conjunction with a Swiss company of milling engineers.

The building was revamped, c.1935. Just the lower courses this building survive today.

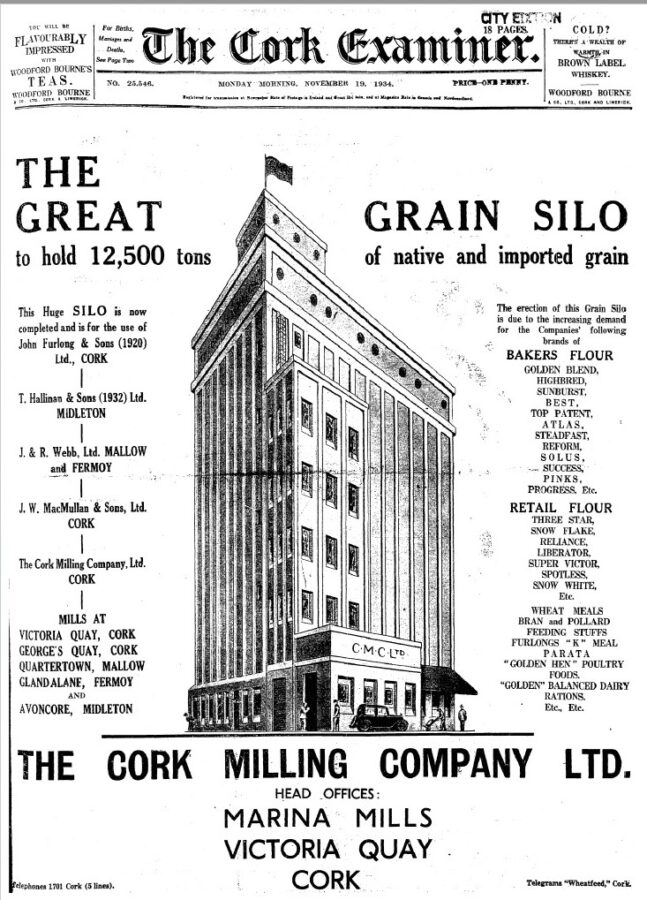

A New Name, Cork Milling Company: By the time of the Irish Free State government, the Cork Milling Company was formed and took over the Cork National Flour Mills site. It was greatly influenced by the imposition of tariffs on foreign-milled flour, and the Government’s invitation to put up mills within the emerging Free State. The Cork Milling Company, Ltd. comprised John Furlong & Sons (1920) Ltd., Marina Mills, Cork, J. and R. Webb, Ltd., Mallow Mills, Mallow and Glandalane Mills, Fermoy; T. Hallinan & Sons (1932) Ltd, Avoncore Mills, Midleton; and J. W. MacMullen & Sons, Ltd., Cork.

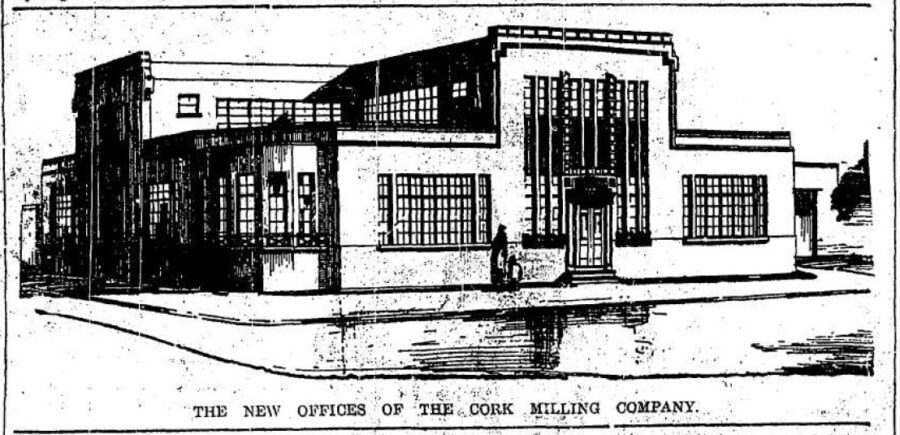

New Offices (1932): In September 1932, in order to accommodate adequately their staff, the Cork Milling Company opened new offices on Victoria Quay. The building was erected on an almost triangular site with two street frontages, and the main entrance was placed on the more important Victoria Road. Externally the building has modern tendencies which are accentuated by the shape of the site and the treatment of the first floor. Internally the ground floor was designed to accommodate a very large staff in the general office, which has a floor area of 1,700 sq. feet, with three directors’ rooms in addition.

New Plant (1934): The work of preparing the plans for a building capable of housing a modern flour-milling plant was entrusted to the noted Cork architects, Messrs Chillingworth and Levie, and in September 1933 work began on the erection and completed in July 1934. The contractors for the building were Messrs. John Sisk and Son.

According to the Cork Examiner, although there was an original building on the present site, the work entailed a large amount of engineering skill, and, thanks to the Consulting Engineer Mr J L O’Connell, the reusability of adapting the older premises as a mill, was accomplished. The original walls were supported on timber piles. These walls were raised considerably and the original floor area was doubled, and in order to ensure a thoroughly substantial job, a complete framework of steel was raised up within the main walls, each stanchion of which was supported by a concrete pile, the idea being to save the original fabric from damage by vibration.

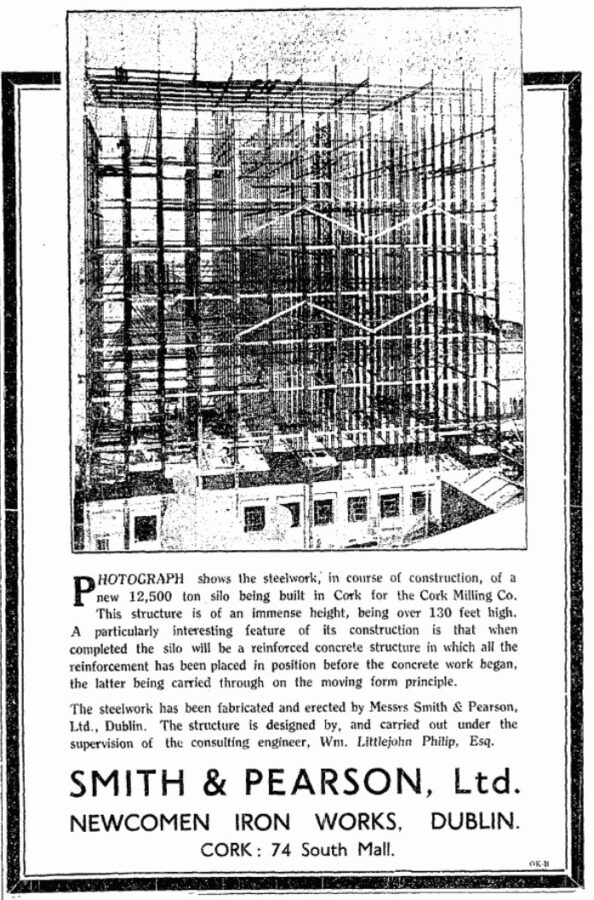

New Grain Silo (1934): In 1934, the Cork Examiner reported that the construction of a twelve thousand five hundred tons Grain Silo was finished at the Marina Mills, Victoria Quay for The Cork Milling Company.

The Company engaged the services of English engineer Mr William Littlejohn Philip, O.B.E., a consulting engineer, whose very extensive knowledge and experience in storing grain in bulk in deep bins was well-known. He was a world expert in the bulk-handling of grain and coal and designed silos in many parts of the world, including Ireland. The imposing structure on Victoria Quay, built to his designs was an outstanding landmark in Cork for its day.

The huge mass of 600 tons of internal steel structure was completed by Messrs. Smith & Pearson, Ltd. of Dublin. A large number of additional and local hands were employed by the concreting contractors to assist and expedite the process of erection.

The foundations and the entire concrete work on the building, to the designs of the consulting engineer, were carried out by Messrs Peter Lind & Co., Ltd., of London.

The method of concreting entails the pouring in of liquid cement simultaneously over the whole area, so that every twenty-four hours the mass rose four feet, and so on, every day, to the top. Sand came from local pits. Four thousand tons of Granite chips were brought by Steamer from Browhead, Goleen. These chips were mixed with several thousand tons of cement and sand, and this concrete was knitted, into one solid mass by thousands of intermingling re-inforcing rods throughout the whole area of the structure.

Contained in the building there was over five hundred tons of steel, and overall the building represented a dead weight of over twenty thousand tons. The total height of the building to the top of the elevator tower from street level is 1,35 feet,

The foundation for a heavy mass of this nature, involved careful consideration, Over 400 ferro-concrete piles averaging about 35 feet long were driven into a deep bed of hard dense gravel in order that the carrying capacity of each pile is absolutely assured. All the piles after being driven down are tied together at the top by a massive concrete beams 3′ x 0″ deep, averaging 7′ 0″ wide heavily reinforced by steel roads so designed and placed that the load coming on the foundation was equally distributed.

Second New Mill and Screenhouse (1936): Constructed of the latest type of re-enforced concrete in 1936, the mill and screenhouse were both five storeys high. The block of buildings were erected by Messrs. P. J. Hegarty and Sons, Builders and Contractors, Upper John Street. The mill proper had a slated and glass roof and the screenhouse, where the wheat was prepared for the mill has a flat roof. The floors were spacious and steel framed windows admitted an abundance of light and ventilation so necessary to an industry producing the most widely used article of human food.

The Cork Examiner on 12 August 1936 describes that the new mill drew wheat automatically from either of the 110-ton bins in the Silo, also from a 5,000 ton grain warehouse adjoining. The wheat was treated to a most elaborate series of separation, scouring, grading washing, drying, brushing, aspirating, etc., and was fitted with machinery enabling exact control to be exercised at each operation while the wheat flowed through a network of elevators, conveyors, spouts, etc., to the final grinding bins.

R & H Hall’s Re-branded Grain Silos (1950s):

R & H Hall was one of Ireland’s biggest importers and suppliers of animal feed ingredients for feed manufacturers. The company was established in 1839 and sometime in the mid twentieth century used the iconic 1930s grain stores on Cork’s quays.

The company was bought by the IAWS Group in September 1990. It has operations at deep-water port locations at Cork city, Ringaskiddy, Dublin, Waterford, Foynes and Belfast, and provides a specialised bulk cereal handling, drying, screening and storage service.

The company’s Cork complex is part of a site earmarked by the City Council for a multi-billion docklands regeneration project.

In Spring 2024, the grain silos were demolished.

In February 2025, some 16,000 tonnes of crushed concrete, the remnants of the R&H silos, will be used to upgrade the Midleton to Cork rail line, a decision estimated to save the equivalent in CO2 emissions of what 85 long-haul flights could be expected to generate (c18,000 kg/CO2), or the electricity consumption of about 250 households a year.

Read more here: Crushing end to R&H Hall silos as rubble is recycled for Midleton rail line upgrade, https://www.irishexaminer.com/property/developmentconstruction/arid-41582839.html?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR368aE5KL-kei0h-ndV8DpyWgnzgSd-ErcjfqnCT2gsRTpmIspTVArwfUM_aem_3dcD_L2fjpFIXtig5iwkqw

The Iconic Odlums Building & its Future:

The “Odlums” iconic building was constructed initially in the 1890s by the Cork National Flour Mills and was revamped in the mid 1930s. Odlums operated their flour mills venture there from 1965 for a time. The building now re-awaits a new purpose in the present day re-configuration of Cork’s South Docks.

In May 2023, planning permission was granted by Cork City Council for Conservation works including part demolition, alterations, extension and change of use of the Odlum’s Building to provide for; retail and/or café use, office space, conference facilities, food and beverage space, a cinema including a bar/ dining area, a bar/restaurant and 84 no. apartments.

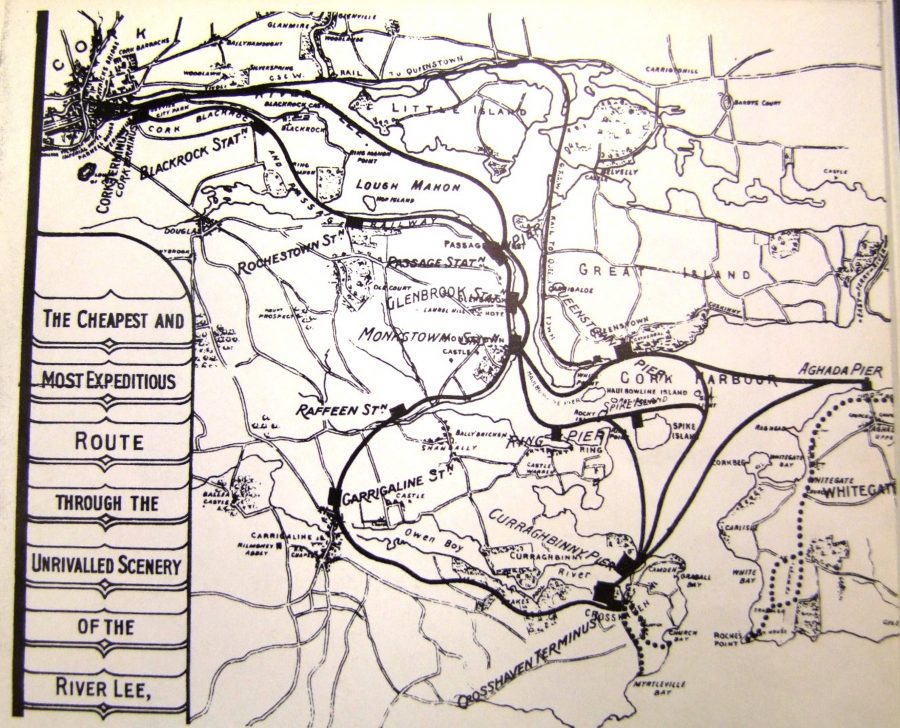

The Old Cork-Blackrock & Passage Railway Terminus:

As new residence areas emerged in the developing city of the nineteenth century, new modes of suburban transport were created. County and national rail links were developed. By the late 1800s, there were five county railway lines and one national line, all of which operated in and out of Cork City. Among the first of the suburban railway projects to be completed in Cork was the Cork Blackrock and Passage Railway on the south bank of the River Lee Estuary.

The year 1836 marked the opening of Ireland’s first railway, between Dublin and Kingstown. A year earlier in 1835, the plan for a Cork to Passage railway was first proposed by Cork based merchant, William Parker and Cork solicitor, J C Besnard. In that year, Cork Harbour town Passage West had its own dockyard and had become an important port for large deep-sea sailing ships whose cargoes were then transhipped into smaller vessels for the journey up-river to the city. The transhipment would be faster by train. In the summer of 1835 a committee was set up to plan the railway. The Cork Harbour Board, the British Treasury and other bodies were approached for financial support.

Charles Vignoles was appointed engineer of the venture. The proposed line would run close to the south of the Navigation Wall (now the site of the Marina) on reclaimed land and remain close to the river to Passage. Work began in June 1847. Due to the fact that the construction was taking place during the Great Famine, there was no shortage of labour. The entire length of track between Cork and Passage was in place by April 1850 and within two months, the line was opened for passenger traffic.

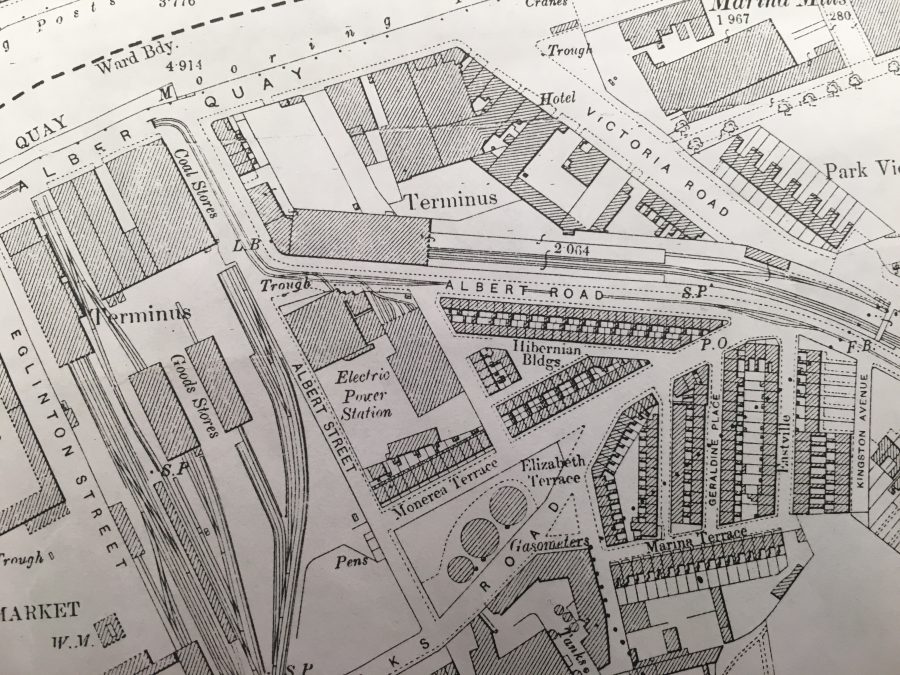

The terminus, designed by Sir John Benson was based on Victoria Road but due to poor press was moved in 1873 to Hibernian Road.

In the late 1800s, the Cork Blackrock and Passage Railway also operated a fleet of river steamers in competition with River Steamer Company (R.S.C). The Railway Company expanded its fleet in 1881 but it was only when the service was extended to Aghada that profits grew.

By 1932, the increase in the use of motor cars caused a decrease in the use of the line by passenger. Consequently, the railway was forced to close. Much of the traces of the Cork-Blackrock line have been destroyed while the Blackrock-Passage section is now a pedestrian walkway with several platforms and the steel viaduct that crossed the Douglas viaduct still in public view. The site of the second Cork terminus lies opposite the National Sculpture Factory.

Former Cork Bandon Railway Terminus:

Providing access between West Cork and Cork City for the general public including visitors and farmers was the Cork Bandon and South Coast Railway line. The Cork-Bandon line opened to the public on 6 December 1851. The Cork terminus was on Albert Quay, which had three passenger platforms, a carriage storage area, and sidings into the Cork Corporation’s stone yard and into the corn market. Feeder lines were also added in the early twentieth century to the roller-milling complex on Victoria Quay and to the Ford tractor works on Cork’s Marina.

Today Ireland’s tallest building the Elysian tower occupies the railway yards. The Cork-Bandon Railway Project was an enormous undertaking. The main parts included; the longest railway tunnel in Ireland at Goggins Hill; the Chetwynd Viaduct; a short tunnel bridge under old Blackrock Road near the Albert Quay Terminus; 21 cuttings, 19 embankments and 15 road bridges.

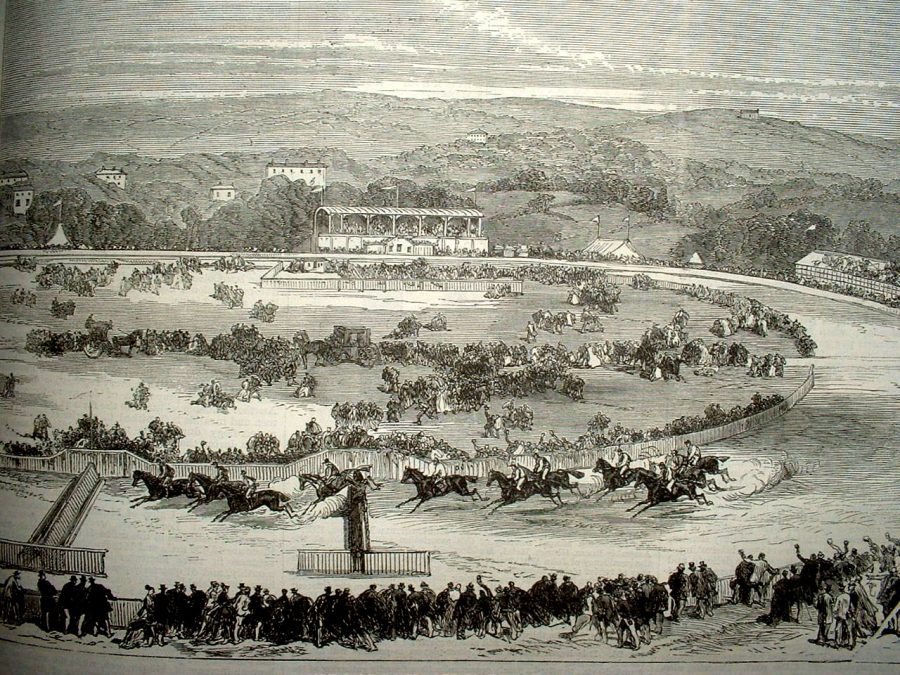

Cork Park Racecourse & Fords:

Centre Park Road crosses the new and proposed South Docklands area adjacent the National Sculpture Factory. However at one time racecourse activities and a Ford Factory were in operation here. In March 1869, Cork Corporation leased to Sir John Arnott and others slobland for a term of five years and for the purpose of establishing a race course. There were no systematic attempts at drainage. So races were held in mud and slush on many an occasion. The first races were held on 17 May and 18 May 1869. A total of 30,000 people attended. In 1892, the City and County of Cork Agricultural Society leased a space from Cork Corporation in the eastern section of the Cork Park. That later became the Cork Showgrounds.

Cork Ford Works:

In November 1916, Fords made an offer to purchase the freehold of the Cork Park Grounds and considerable land adjoining the river near the Marina. Fords, Cork Corporation and the Harbour Commissioners entered into formal negotiations. The Company acquired approximately 130 acres of land, which also had a river frontage. The factory gave employment to at least 2,000 adult males paid the minimum wage of one shilling per hour.

The plant being laid down by the company was specially designed for the manufacture of an Agricultural Motor Tractor, well known as the ‘fordson’, a 22 horse power, four cylinder tractor, working with kerosene or paraffin, adaptable either for ploughing or as a portable engine arranged for driving machinery by belt drive. The tractor was articulated, i.e. it had no frame giving accessibility to all parts for making adjustments, the motor, transmission and rear axle being assembled in one rigid unit. The casing was of special design and the pistons and gearing were of Vanadium steel. All moving parts were enclosed. The demand for such tractors was universal and great. Large areas could be brought under food production with the minimum of expense and labour. The Cork factory was to provide ‘Fordsons’ to local, regional and national farmers and further afield on the European Continent.

Watch RTE documentary piece here on the Ford Plant in Cork:

Watch a TG4 news piece on the Ford Plant here:

Victorian Architecture on Victoria Road:

Contrasting against the residences of the working class were the highly embellished Victorian residences which can be seen on Victoria Road named after Queen Victoria. Mid nineteenth century society was highly status-conscious and nothing displayed your status like your house. House fashions literally started at the dinner table. Most wealthy Victorians spent what would seem to us to be an incredible amount of time socializing: it was not uncommon for them to either attend or host a dinner party two to five times a week.

In short, your social circle saw your house a lot, so it was important that the house be impressive — that is, designed in the latest fashion. The house of a successful Victorian family was more than merely a home; it was a statement of their taste, wealth, and education. The Victorians drew deeply from history, nature, geometry, theory, and personal inspiration to create their designs. At the top end of the market, builders employed a reputable architect.

The mid to late nineteenth century Victorian buildings were varied and colourful. Architectural embellishment was ever present. Designs sprang from the relationship between social forces, ideals, techniques and individual preference. As the mid to late 1800s ensued, there was increasing interest in foreign styles such as French, Italian Gothic and French Renaissance. In most cases, mixes of medieval styles were reinvented.

In the late 1800s, the favoured architectural style in housing was High Victorian Gothic, which provided aristocracy and landed gentry with houses, which were spectacular and richly ornamented. This style harked back to medieval castles and cathedrals. Its growth in popularity came simultaneously with romantic movements in all the arts, that is, simultaneously with the infamous Victorian taste for melodramatic music, plays and novels. The Gothic Revival house is characterized by steeply pitched roofs, pointed-arch windows, elaborate vergeboard trim along roof edges and other Gothic details. The style appears in Cork in the 1870s and 1880s and appears on Victoria Road.

(JFK) Kennedy Park:

Perhaps it was a message of hope that he carried on his visit to Ireland and to cities such as Cork on his way back to the US from Berlin in June 1963. Indeed, he received the freedom of Cork, Dublin, Galway, Limerick and Wexford. President Kennedy’s itinerary meant that helicopter was his means of transport on trips through the country. The Minister for External Affairs, Mr Aiken and the American Ambassador, Mr McCioskey travelled in the President’s helicopter. The Minister for Industry and Commerce Jack Lynch travelled in another helicopter and visiting pressmen and officials travelled in two similar craft.

The rain, which had been threatening during the morning held off for the commencement of his visit. As the President alighted at Collins Barracks, a pipe band drawn from the 4th Batallion, Limerick under Sergeant Walter O’Sullivan. The President gave the crew cut White House security men an unexpected problem when he arrived in Cork. Flanked on both sides by security men, he suddenly changed course and went to a window at Collins Barracks where a group of Army nurses were waving frantically and calling “Mr President”, Mr President. With a broad grin he strode across to them and with an outstretched hand greeted them individually.

Half an hour before President Kennedy arrived in Cork, an emergency call went out from the secret service that one of the two open cars to be used in the procession had broken down. Twenty minutes later a Cork firm had supplied a black 1937 Rolls-Royce. As the motorcade progressed towards the city centre the crowds thickened. Again and again his car had some difficulty in getting through and had to stop more than once. The effective crash barriers in Parnell Place stood up well to surging crowds and all Cork wanted to get a glimpse of the smiling young President as he was brought through the streets.

In McCurtain Street a large banner erected by the ITGWU spanned the roadway issuing ‘céad míle fáilte’ to the President. One of the biggest crowds was the foot of Patrick’s Hill where Gardai had trouble holding back the crowds. On more than one occasion thousands surged forward in an attempt to reach the President’s car but the Gardaí succeeded in maintaining a narrow passage, which was just big enough to allow the procession through.

At Cork City Hall the Cork Lord Mayor, Alderman Seán Casey, TD, opened his address to Kennedy by noting:

“You stand for the weak against the strong, for right against might”. Continuing the Lord Mayor noted that Kennedy was receiving the honour “in token of our pride that this descendant of Irish emigrants should have been elected to such an exalted office and of our appreciation of his action in coming to visit the country of his ancestors; as a tribute to his unceasing and fruitful work towards the attainment of prosperity and true peace by all the people of the world, and in recognition of the close ties that have always existed between our two countries”.

The Freedom of Cork casket was decorated with Celtic designs and on the lid the arms of Cork were engraved. On the front was the American Eagle Crest and on the back of the crest of the Kennedy family.

In a well measured speech, one of Kennedy’s key points referred to Ireland’s hope and mission for freedom through the ages: “So Ireland is still old Ireland but it has found a new mission in the 1960s and that is to lead the free world to join with other countries in the free world to do in the 60’s what Ireland did in the early part of this century and indeed has done for the last 800 years and that it associates itself intimately with the principle of freedom”.

As the crowds swelled outside City Hall to get a glimpse of the President, Kennedy’s motorcade struggled as it made its way to Monahan Road to reach his helicopter for his return flight to Dublin. Despite the troops drawn from Collins Barracks and Sarsfield Barracks and the 1st Motor Squadron, the public seized their opportunity here and swarmed around the presidential helicopter and gave him a send-off that equalled anything he received to that date on his Irish visit.

A year later the site from where JFK took off from Monahan Road was renamed Kennedy Park.

Watch JFK’s speech during his Freedom of Cork City in 1963:

Commemorative Walking Tour with Kieran McCarthy marking 50 years of the taking off of his helicopter from Monahan Road on 28 June 1963.

Jewtown on Albert Road:

Immortalised by the name Jewtown, Albert Road and the area of the Hibernian Buildings have been imbued by the story of the Jewish community. The Cork Jewish Congregation was founded about the year 1725 with Shocket and cemetery. It comprised Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews engaged in import and export. By 1871, there were nine Jews in Munster. During the Russian oppression which preceded the May Lass of 1881, several Jews of Vilna, Kovno and Ackmeyan, a Lithuanian village, came to live in Cork. A congregation was formed at the close of 1881 and Meyer Elyan of Zagger, Lithuania was appointed Shocket, Reader and Mothel. The community had close links with those of Dublin and Limerick.

Several of the earliest arrivals from a cluster of shtetls in north-western Lithuania settled in a group of recently constructed dwellings called Hibernian Buildings, Monarea Terrace and Eastville off the Albert Road, c. 1880. Much of the streetscape is as it was more than a century ago when the first Litvaks arrived. Hibernian Buildings was a triangular development of a hundred or so compact and yellow brick on street dwellings.

Each housing unit consisted of four rooms, including a bedroom up in the roof. Seventy Jews prayed in a room in Eastville. About the year 1884, a room was rented in Marlborough Street from the Cork Branch of the National League. A synagogue was fitted up in the offices there. Premises were finally acquired at 24 South Terrace. The number of Jews in the city and county combined rose from twenty-six in the year 1881 to 217 in the year 1891.

The O’Flynn Brothers, based in Blackpool, were responsible for the construction of the Hibernian Buildings as well as the Rathmore Buildings, St. Patrick’s Hospital, The Good Shepherd Convent, Magdalen Asylum, additions to Our Lady’s Hospital, a new presbytery at the North Cathedral, and the Diocesan College at Farranferris.

Watch a documentary on Jewish Cork History here:

Shalom Park’s Evening Echo Lighting Installation:

Evening Echo is sited on old gasometer land gifted by Cork Gas Company to Cork City Council in the late 1980s, and subsequently dedicated as Shalom Park in 1989. The park sits in the centre of an old Cork neighbourhood known locally as ‘Jewtown.’ This neighbourhood is also home to the National Sculpture Factory. Not a specific commission, nor working to a curatorial brief, Evening Echo is a project generated as an artist’s response to the particularities of a place and has quietly gathered support from Cork Hebrew Congregation, Cork City Council, Bord Gáis and a local Cork newspaper, the Evening Echo.

References to the slow subsidence of the Jewish community in Cork have been present for years, but there is now a palpable sense of disappearance. Within the Cork Hebrew Congregation there are practical preparations underway for this, as yet unknown, future moment of cessation. Evening Echo moves through a series of thoughts and questions about what it might mean to be at this kind of cusp, both for the Jewish community and for other communities in Cork.

Evening Echo is manifested in a sequence of custom-built lamps, remote timing systems operated from Paris, a highly controlled sense of duration, a list of future dates, an annual announcement in Cork’s Evening Echo newspaper and a promissory agreement. Fleetingly activated on an annual cycle, and intended to exist in perpetuity, the project maintains a delicate position between optimism for its future existence and the possibility of its own discontinuance.

Maddie Leach’s work is largely project-based, site responsive and conceptually driven and addresses new thinking on art, sociality and place-based practices. She seeks viable ways of making artworks in order to interpret and respond to unique place-determined content and she is recognised for innovatively investigating ideas of audience spectatorship, expectation and participation in relation to art works. Leach’s projects include commissions for Iteration: Again (Tasmania, 2011), Close Encounters (Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, 2010), One Day Sculpture (2008), the New Zealand publication Speculation for the Venice Biennale 2007 and Trans Versa (The South Project, Chile, 2006).

Read more on Maddie Leach here: Maddie Leach | Evening Echo

Cork Gas Works:

By 1823, numerous towns and cities throughout Britain were lit by gas. Gaslight cost up to 75% less than oil lamps or candles, which helped to accelerate its development and deployment. By 1859, gas lighting was to be found all over Britain and about a thousand gas works had sprung up to meet the demand for the new fuel. The brighter lighting which gas provided allowed people to read more easily and for longer.

In 1825 the Cork Wide Street Commissioners, a municipal planning agency of sorts, entered into an arrangement with the United Gas Company of London to provide Cork City with gas lighting between the hours of sunset and sunrise, with each gas lamp to provide light equivalent to that of twelve mould tallow candles. The United Gas Company’s network served the city between 1826 and 1859.

By the mid-1850s local interest groups began to mount a strong and ultimately successful challenge to the monopoly exercised by the United General Gas Co. of London. John Francis Maguire (1815-72), proprietor of the Cork Examiner and a staunch advocate of economic nationalism curbed the influence and monopoly and incorporated a rival gas company – the Cork Gas Consumers’ Company, acquired a three-acre site for its own proposed gasworks adjacent to the London one. Work began in January 1857. 36 miles of service pipes laid and 43 miles of mains. The site today is now occupied by the national offices of Bord Gais.

Cork’s Electric Trams:

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, the Corporation of Cork planned to establish a large electricity generating plant. The plant would provide public lighting and operate an electric tramcar extending from the city centre to all of the popular suburbs. The site of the new plant was on Monarea Marshes (now the National Sculpture Factory) near the Hibernian Buildings.

The Electric Tramways and Lighting Company Ltd. was registered in Cannon Street, London and had a close working relationship with eminent electrical contractors, the British Thomson-Houston Company. This latter English company were appointed the principal contractors.

The street track was completed by William Martin Murphy, who was a Berehaven man, but with a company in Dublin. William was the first chairman of the Cork Company.

Leading Cork housing contractor, Edward Fitzgerald, soon to become Lord Mayor of Cork, completed the building of the plant. To provide proper foundations for the large plant, extensive quantities of pitch pine were sunk under the concrete.

Mr. Charles H. Merz, one of British Thomson-Houston’s up and coming engineers, supervised the electric tramcar system. He became the secretary and head engineer for the Cork operation. Charles was a native of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and arrived in Cork during the laying of track and near completion of the plant.

Eighteen tramcars arrived in 1898 for the opening, which occurred on 22 December. Cork was to become the eleventh city in Britain and Ireland to have operating electric trams. Four of the six suburban routes were complete for the line’s commencement. The eventual termini included Sunday’s Well, Blackpool, St. Luke’s Cross, Tivoli, Blackrock and Douglas.

By 1900, 35 electric tram cars operated throughout the city and suburbs. They were manufactured in Loughborough, U.K. and all were double deck in nature, open upstairs with a single-truck design. Most tram cars could hold at least 25 people upstairs and 20 downstairs. However, a key rule on the tram was that nobody could sit or stand on the driver’s front platform!

Take a tram ride from King Street to St Patrick’s Bridge, Cork (1902), filmed by Mitchell & Kenyon

Municipal Electricity Supply:

The supply of electricity to the City was in the hands of the Cork Electric Tramways and Lighting Company, Ltd, who started operations in 1898. The Power House was situated near the River Lee at Albert Road, and also housed the trams at night. A maintenance crew were present if repairs needed to be carried out.

The business of providing electric power grew significantly from 1.8 million units in the year 1900 to 4.9 million units in the year 1916. The connections to the company’s mains for lighting purposes at the end of 1916 were equivalent to 102,000 eight candle power lamps. There was a considerable demand for current for heating and cooking. The electricity supply was ‘direct’ in nature and generated 500 volts to operate the trams that ran through the city’s streets.

In about 1925, the name of the company was changed to The Cork Electric Supply Co. Ltd. The closure of the tramways in 1931 and the coming of the E.S.B. had a huge impact on the Albert Road depot. The company made great strides to replace the city’s gas lamps, all of which did not completely disappear until 1936. However, advancing the tramway network or saving it were not key agendas for the early twentieth century proprietors.

On 30 September 1931, the final abandonment of the trams occurred. Fireworks, cheering and souvenir collecting were all aspects of general public’s final goodbye. Many of the ex-tram staff were taken and employed by the Irish Omnibus Company whilst others went to work in the E.S.B.

As an electricity generating station and tram-house, the building has an important connection with the industrial history of the city. It is of continuing cultural significance through its present use as the National Sculpture Factory.

The Factory was set up in 1989 by four local artists as a response to a need from artists for a large scale well equipped studio space where they could work. The National Sculpture Factory is a national organization, dedicated to artists, which advances the creation and understanding of contemporary art.

Watch creative work at National Sculpture Factory:

The Elysian Tower:

Archiseek records that The Elysian is a mixed-use complex of a number of connected 6-8 storey buildings, with a landmark 17-storey tower on the southwest corner of the site. Designed by Frank O’Mahony Architects, the tower is 71 metres (233 ft) to the top floor, making it the tallest storeyed building in the south of Ireland, surpassing the 67-metre County Hall, also in Cork.

On 8 December 2006, the final section of the lift shaft of the 72-metre high Elysian apartment tower in Cork city centre was put into place.

Two teams of 31 workers worked around the clock to pour 4,500 tonnes of reinforced concrete to a height of 72 metres at the O’Flynn Construction tower, which is being built by PJ Hegarty & Co.

A Polish work crew did the painstaking, 12-hour, concrete-shovelling shifts by day and a similar-sized Portuguese crew worked through the night for 18 days of continuous pour to usurp Cork’s County Hall (68 metres) as the country’s tallest building. The 18-storey tower’s core offers dramatic bird’s-eye views of the city.

A decorative pinnacle gives The Elysian’s tower an overall height of 81 metres. At a cost of €150 million, The Elysian was officially opened in 2008.

One Albert Quay:

Another significant South Docks site is One Albert Quay. During the winter of 2015, a former warehouse building on the corner of Albert Quay and Albert Street was completely demolished to make way for the eight-storey building. Developed by John Cleary Developments the building attracted multinational companies interested in setting up business in the city centre.