Cork’s Seventeenth Century Townscape:

In the first decade of the seventeenth century, the town boundaries were changed. A charter granted by James I in 1608 officially extended the limits of municipal jurisdiction from within the town walls by a radius of approximately three miles beyond the settlement. This area became known as the “County of the City of Cork”. The subsequent increase in trade meant that a large new dock was needed. It was constructed on the edges of one of the marshes to the east of the town.

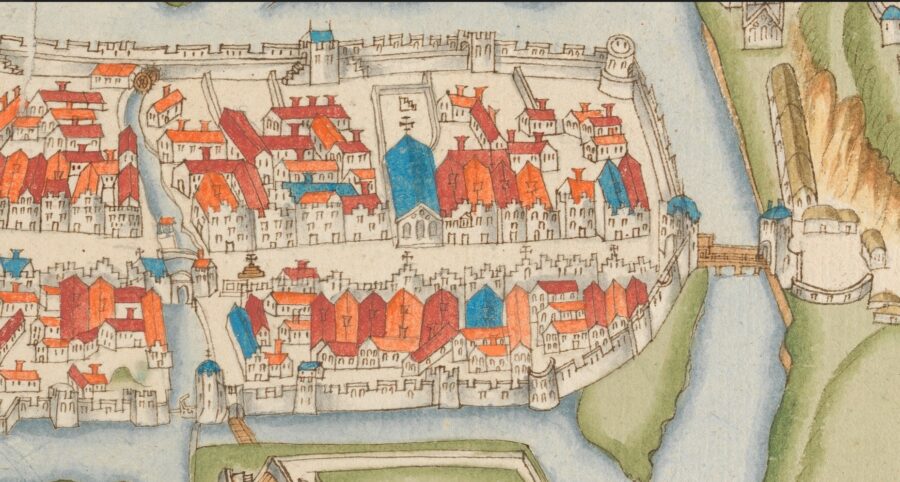

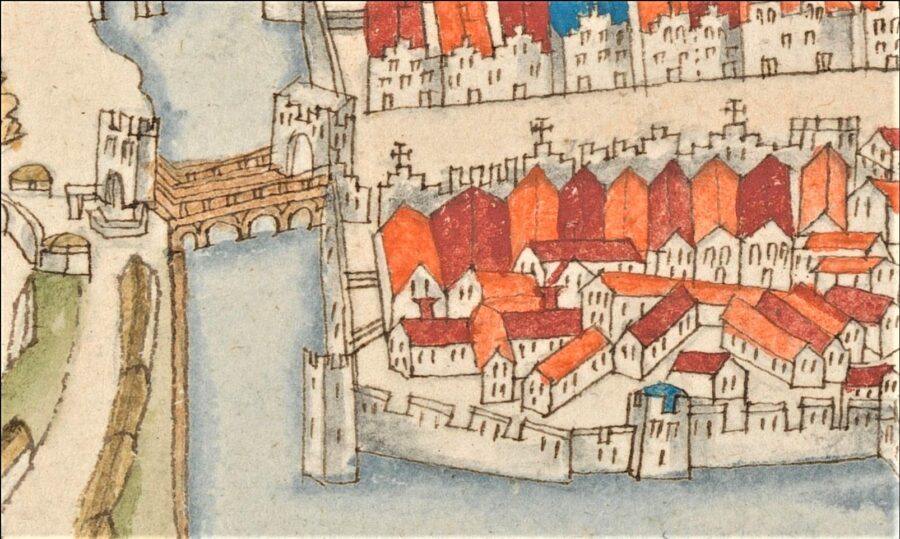

The dock can be seen in John Speed’s depiction of the walled town of Cork in 1610. The dock would have extended from Daunt’s Square, down the northwest side of St. Patrick Street as far as Academy Street, northwards as far as Lavitt’s Quay, westwards to Corn Market Street and then southwards to rejoin Daunt’s Square. The town’s custom house was moved from the centre of the walled town to this new dock. In these old depictions of the walled town the terms town and city are used interchangeably, making it difficult to ascertain when Cork officially became a city.

North and South Main Streets were typically fronted by three-storey buildings. Narrow laneways, twenty-nine in all, are shown extending at right angles from the main streets, eastwards and westwards. Add to this the fifteen routeways, and the total number of streets and laneways was forty-four. Additional buildings are shown, both dwellings and outhouses, and these were constructed well back from the main streets. They are located in the original plots of the Anglo-Norman houses and aligned in a north-south direction. A market cross is also shown, and the drawbridges are illustrated as timber structures.

The years leading up to the mid-seventeenth century witnessed significant changes in the townscape, primarily an increase in the number of streets, lanes and buildings. The Corporation of Cork and the town’s wealthier merchants were central to the creation and modification of the urban townscape. As a result, the 1641 Royal survey of Cork records that the number of streets and laneways in the town had increased to sixty-nine, while in the suburbs it had increased to twenty-four. Thus, the total number of streets and laneways in the urban area in 1641 was 93. The estimated number of domestic dwellings in 1602 in the town and suburbs was c.445, by 1641 the official number given was 1,266 dwellings.

There were also other improvements in the built fabric of the town. During the seventeenth century, the walls and entrances continued to be an integral element of the defences of the town. On 14 November 1639, the Corporation of Cork agreed to build North Gate Bridge with “good and sound timber” and to pave it with sand. They also decided to put similar pavement on the South Gate Bridge. New drawbridge towers were also to be built on the bridges and the river channels were to be cleaned of rubbish.

Challenges of English Colonisation:

The problems arising from English colonisation in the late sixteenth century continued into the early 1600s. Many Irish Catholics felt strong resentment towards the Crown. They refused to accept the new Protestant religion and as a result small, violent rebellions were common. It was at this time that Cork became known as the ‘rebel county’.

Two Irish Chiefs, Hugh O’Neil and Red Hugh O’Donnell were waging all-out war against Queen Elizabeth. In 1600, O’Neil marched to the south of the country, reaching Inniscarra, five miles west of Cork. Here, he met with southern chieftains Florence McCarthy, Lord of Carbery, and Donal O’Sullivan, Lord of Beara. A campaign against English forces was proposed. However, while O’Neil was in the south, 7,000 English foot soldiers and 800 horsemen invaded Ulster. O’Neil was forced to temporarily abandon his campaign in the south and returned north to a struggle of varying fortunes.

During the closing decade of the sixteenth century, O’Neil was in communication with Spain and received occasional aid in the form of arms and monies. However, requests made to Philip II for foot soldiers came to naught. Philip II died in 1598 and was succeeded by his son, Philip III. At the beginning of 1600, Philip III honoured his father’s promise and sent military experts to Ireland to negotiate with O’Neil regarding the sending of a Spanish force.

On 23 September 1601, during a meeting of the Queen Council in Kilkenny, a message was received that a Spanish fleet had arrived off Kinsale Harbour and had taken the town and its environs. Approximately 3,500 Spanish soldiers had landed at Kinsale, 700 at Baltimore. The English responded by sending 2,000 men, under the leadership of Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, to join the 7,000 already stationed in Cork, and the town became a crucial pawn in the attack on the Spanish invaders.

The Spanish leader, Don Juan Del Áquila, sent word for help to O’Neil and O’Donnell. O’Neil immediately left his northern territories and marched south with 4,000 men and 200 horses. Arriving at Kinsale, O’Neil’s army surrounded the town, but were flanked by English despatches and forced to retreat. The English prepared for a lengthy siege of the Spaniards’ positions at Kinsale, Baltimore, Castlehaven and Berehaven. In January 1602, Don Juan Del Áquila agreed to evacuate his troops and the joing Spanish-Irish campaign came to an end.

Advent of James I:

In April 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died and a new Protestant king, James I, was proclaimed. One Captain Morgan was responsible for bringing the news to all Irish towns. In Cork, the messenger was received by George Thornton, one of the Kings’ appointed commissioners for Munster, who relayed it to the mayor of Cork, Thomas Sasfield. The mayor and the citizens of any royal town had the choice of refusing to proclaim a new monarch on the English throne, but this rarely occurred due to the threat of military action. However, in this case, Sasfield was determined to refuse to proclaim the new monarch on the grounds of his religion. He knew he could not refuse outright, so instead he used political loopholes to buy time.

Sasfield used his prerogative to call together all Corporation officials at the town court house to decide on the matter. He knew that other towns had already proclaimed James, so time was short. Sasfield managed to keep Thornton waiting by declaring that the meeting had to be adjourned until the following day. Under the pressure of time, Sasfield and the citizens agreed to arm and forcibly prevent English forces from entering the town. The rebellion was quickly quashed and Thornton proclaimed James I as king. The mayor and several insurgents were executed.

Advent of Charles I:

James ruled until 1624, a time of prosperity for the walled town of Cork but also a time of uncertainty for the civil administration of the town. James was replaced by his son, Charles I. Fearing another Spanish-Irish attack, Charles attempted to win the support of Irish Catholic landlords. He rejected the Oath of Supremacy, to which Roman Catholics objected on religious grounds, in favour of an Oath of Allegiance, which the Catholic landlords swore in return for three annual subsidies of £40,000. Influential Protestant families, such as the Inchiquins and Broghills, publicly questioned Charles’s strategy. They launched a letter campaign to persuade the monarch to change his approach, but their pleas were ignored.

Over time, this situation had a detrimental effect on the financial and social position of the Protestant settlers in Cork. Many Protestant landlords deemed Charles’s support of Catholicism wrong and felt the work of conversion that had been completed in the preceding years was being unravelled.

By January 1649 the King’s own parliament had turned against him and his own MPS ordered his capture and execution. Britain thus became a republic. The Parliamentarians sent a force to Ireland to suppress any pro-Royal sympathy. The army was led by the new Lord Lieutenant in Ireland, Oliver Cromwell.

Advent of Oliver Cromwell:

Oliver Cromwell arrived in Ireland on 15 August 1649 and immediately took control the town of Drogheda after a bloody massacre He then proceeded to Wexford and Ross and sent out small contingents into the Munster countryside to take note of any Royalist military activity. The atrocities visited on the various towns by Cromwell was unprecedented. In October 1649, the Corporation of Cork surrendered before Cromwell even arrived in the area, such was the fear of slaughter. From 1649 to 1683, the Irish Catholic citizens of Cork lived under severe restrictions and were monitored in all aspects of their daily life.

James II Versus William of Orange:

In 1683 a new Catholic King ascended the throne, King James II. The English parliament objected to the new monarch and offered the throne to the Dutch prince, William of Orange. James was forced to flee to Ireland and in March 1688 he arrived at Cork and incited the people to rise up against the Protestant pretender. In the spring of 1689, William led a huge army to Ireland to restore power.

The first confrontation between the Jacobites and Williamites occurred in 1690 on the banks of the River Boyne, where the Jacobites were defeated. James fled south and sailed into exile. After the Battle of the Boyne, William turned his attention to the walled town of Limerick, which was also occupied by supporters of James II. After a summer of major setbacks, William failed to take Limerick and was forced to retreat. At the same time, rebellions against William’s Protestant side escalated in South Munster. However, the English forces were far better equipped and more numerous, easily able to deal with localized rebellions. It is recorded that the governor at Youghal, along with his rebel forces, were forced to surrender to a contingent of English soldiers.

In September 1690 a Jacobite army along with a number of Irish rebel factions combined forces to take control of Cork to provide a stronghold position against King William. The actual number of insurgents is not recorded, but it is likely that several hundred soldiers were involved in the takeover of the walled town. These forces were welcomed by the Catholics in the area. They manned the drawbridges and the town wall-walks, readied numerous buildings and waited for the attack they knew must surely come.

Read more and Explore more: 3c. Siege of Cork, 1690 | Cork Heritage