Abstracted Text

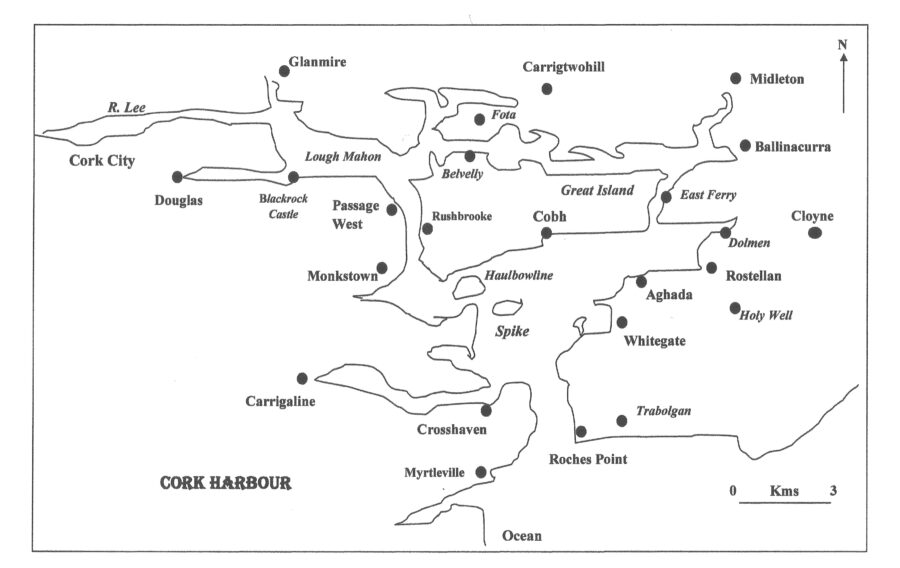

Cork Harbour is a beautiful region of southern Ireland. It possesses a rich complexity of natural and cultural heritage.

My book The Little book of Cork Harbour is published by The History Press (2019). This is a little book about the myriad of stories within the second largest natural harbour in the world. It follows on from a series of my publications on the River Lee Valley, Cork City and complements the Little Book of Cork (History Press, Ireland, 2015). It is not meant to be a full history of the harbour region but does attempt to bring some of the multitudes of historical threads under one publication. However, each thread is connected to other narratives and each thread is recorded to perhaps bring about future research on a site, person or the heritage of the wider harbour.

The book is based on many hours of fieldwork and also draws on the emerging digitised archive of newspapers from the Irish Newspaper Archive and from the digitalised Archaeological Survey of Ireland’s National Monument’s Service. Both the latter digitised sources more than ever have made reams and reams of unrecorded local history data accessible to the general public.

In Cork Harbour colourful villages provide different textures and cultural landscapes in a sort of cul-de-sac environment, with roads ending at harbours and car parks near coastal cliff faces and quaysides. The villages are scattered around the edges of the harbour, each with their own unique history, all connecting in some way to the greatness of this harbour. Walking along several junctures of fields, one can get the feeling you are at the ‘edge of memory’. There are the ruins of old structures that the tide erodes away. One gets the sense that a memory is about to get swept away by the sea, or that by walking in the footsteps trodden by writers, artists and photographers 100 years ago, one could get carried away by their curiosity.

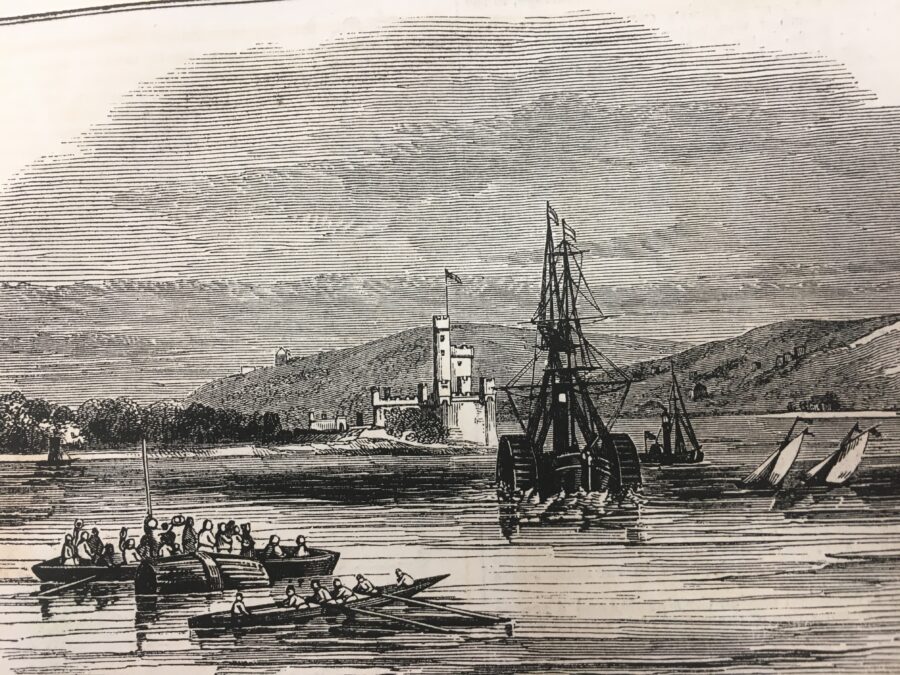

On any good weather day, there are parts of the region where one can almost drive across its sun kissed mudflats. From the Cork-Midleton dual carriage way you get to appreciate farmer’s attempts of reclamation through the ages and the broad mudflats which serve as a home for international bird habitats. There are sections of the harbour to be viewed from the road, which seem almost forgotten. I am a big fan of the Smith Barry tower house folly, which belonged to Fota House estate and which exists on the edge of the Fota golf course.

For centuries, people have lived, worked, travelled and buried their dead around Cork’s coastal landscapes. The sea has been used a source of food, raw materials, as a means of travel and communications and as a place to build communities. Despite this, the harbour has very distinct localities and communities. Some are connected to each through recreational amenities such as rowing or boating and some exist in their own footprint with a strong sense of pride. Some areas such as Cobh and the military fortifications have been written about frequently by scholars and local historians whilst some prominent sites have no words of history or just a few sentences accorded to their development.

Book Contents

In the book the section, Archaeology, Antiquities and Ancient Towers explores the myriad of archaeological finds and structures, which survive from the Stone Age to post medieval times. Five thousand years ago, people made their home on the edge of cliffs and beaches surrounding the harbour. In medieval times, they strategically built castles on the ridges overlooking the harbour.

The section, Forts and Fortifications, explores the development of an impressive set of late eighteenth-century forts and nineteenth century coastal defences. All were constructed to protect the interests of merchants and the British Navy in this large and sheltered harbour.

The section, Journeys Through Coastal Villages, takes the reader on an excursion across the harbour through some of the region’s colourful towns. All occupy important positions and embody histories such as native industries, old dockyards, boat construction, market spaces, whiskey making and food granary hubs. Each add their own unique identity in making the DNA of the harbour region.

The sections, Houses, Gentry and Estates and People, Place and Curiosities, respectively are at the heart of the book and highlight some of the myriad of people and personalities who have added to the cultural landscape of the harbour.

The section, Connecting a Harbour, describes the ways the harbour was connected up through the ages, whether that be through roads, bridges, steamships, ferries, or winch driven barges.

The eighth section, Tales of Shipping, attempts to showcase just a cross-section of centuries of shipping, which frequented the harbour; some were mundane acts of mooring and loading up goods and emigrants but some were eventful with stories ranging from convict ships and mutiny to shipwrecks and races against time and the tide.

The section entitled Industrial Harbour details from old brickworks, ship buildings to the Whitegate Oil refinery. Every corner of the harbour has been affected by nineteenth century and twentieth century industries.

The last section Recreation and Tourism notes that despite the industrialisation, there are many corners of the harbour where GAA and rowing can be viewed as well as older cultural nuggets such as old ballrooms and fair grounds. This for me is the appropriate section to end upon. Cork Harbour is a playground of ideas about how we approach our cultural heritage, how were remember and forget it, but most of all how much heritage there is to recover and celebrate.

Prehistoric Cork Harbour

The Mesolithic Harbour:

About ten thousand years ago, the first human settlers, hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic or Late Stone Age era came to Cork Harbour. Just over 25 shell midden sites are marked on maps created by the archaeological inventory of Cork Harbour – some of these have not survived; some survive just in local folklore. Some have been excavated throughout the twentieth century. There have also been unrecorded sites eroded away by the tide or by cliff collapse. Shell midden sites consist of refuse mounds or spreads of discarded sea-shells and are normally found along the shoreline. Shellfish were exploited as a food source and sometimes as bait or to make dye. In Ireland shell middens survive from as early as the Late Mesolithic but many of the Cork Harbour oyster middens have also been dated to medieval times while some have produced post-medieval pottery dates.

Over a quarter of all identified middens in the Cork Harbour area are to be found at eight locations in Carrigtwohill parish. When surveyed by the archaeologist Reverend Professor Power in 1930 a midden on Brick lsland (in the estuary to the north of Great Island, joined to mainland by narrow neck of land) measured five or six feet thick at the terraced shore edge and extended along the foreshore for over one hundred and eighty yards and inland for seventy or eighty feet. It contained nearly pure oyster shells with occasional cockle, mussel, whelk and other marine shells. Thin layers of charcoal were visible in many places and stone pounders or shell openers visible in many places.

In 2001, archaeological monitoring of a 15-hectare greenfield site at Carrigrenan, Little Island, was carried out prior to the construction of a waste water treatment plant by Cork Corporation. Two shell spreads along the western seashore perimeter of the site were noted. A polished stone axe was recovered during topsoil monitoring and has been given a possible late Mesolithic date. All other finds were random pottery, eighteenth to twentieth century in date.

Smaller middens for example at Curraghbinny, Currabally and Rathcoursey reflect shorter periods of use. At the western end of Carrigtwohill in 1955, archaeologist M J O’Kelly prior to the construction of a new school excavated oyster shells, few animal bones and fragments of glazed pottery dating to late thirteenth century /early fourteenth century.

The Mystery of the Rostellan Dolmen:

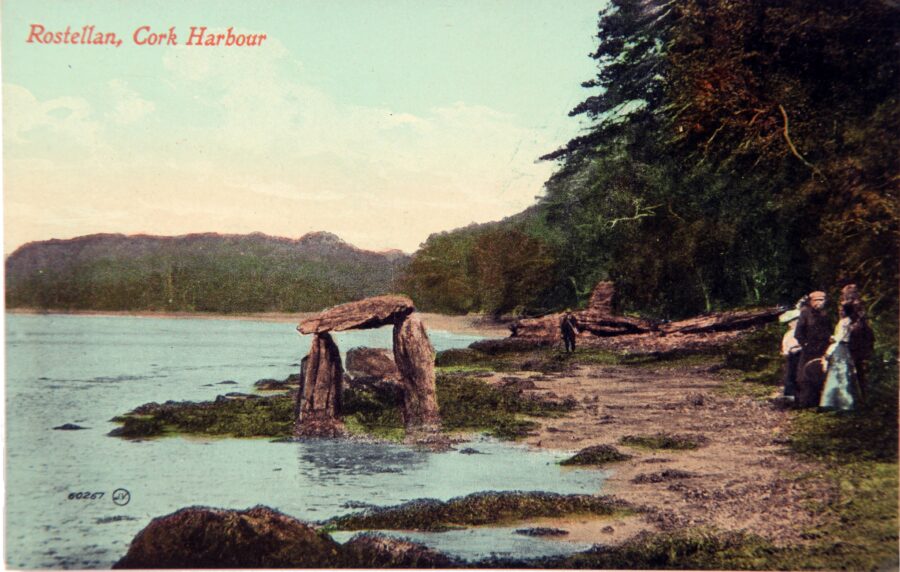

Described as enigmatic by Cork archaeologists, the dolmen in Rostellan in eastern Cork Harbour is similar to portal tombs but here cannot be confidently identified as such. The monument has three upright stones and a capstone, which at one time fell down but was later re-positioned. The site gets flooded at high tides and is difficult to get to across the local mudflats. It is easier to get to it with a guide through the adjacent Rostellan wood. The wood was created as part of the former estate of Rostellan House. The house was built by William O’Brien (1694-1777) the 4th Earl of Inchiquin in 1721. The Dolmen could be a folly on the estate. There is a folly in the shape of a castle tower, named Siddons Tower, after the Welsh-born actress Sarah Siddons, nearby.

The Giant’s Circle:

The name Curraghbinny in Irish is “Corra Binne”, which is reputedly named after the legendary giant called Binne. Legends tells that his cairn (called a “Corra” in Irish) is located in a burial chamber atop the now wooded hill. The cairn is not marked in the first edition Ordnance Survey map, but its existence was noted during the original survey in the Name Books compiled at that time. John Windle, the well-known Cork writer and antiquarian of the early nineteenth century, mentions the site in his publications. There is no record though in his printed works or in his manuscripts preserved in the Royal Irish Academy Library of any digging having taken place at the cairn.

In 1932 archaeologist Seán P Ó Riordáin and his team excavated the 70 feet in diameter cairn (with its greatest height being 7 ½ feet). On one flat stone forming part of the inner arc they found a group of about one hundred pebbles, water-rolled, and such as would come from a brook, while a second group of about sixty pebbles was found just north of the western end of the arc. At the centre of the mound they came upon a peculiar structure of stones and clay. The clay was raised to a height of about 4 inches above the surrounding surface, and the stones were embedded in it.

The most interesting discovery was made on the south side of the cairn. In a space between two stones of the kerb and a third lying just inside the team found, mixed with a thick layer of charcoal, some burnt bone fragments. Examination proved these to be human. The charcoal deposit with which the bones were found mixed did not extend under the neighbouring large stones. This showed that the fire was lit after the boulders had been placed in position. The cremated human bone found nearby was carbon dated roughly to be 4,000 years old. A small bronze ring, about five-eighths of an inch in diameter, was found outside the kerb on the south-east side.

The Lights in the Dark

Roches Point Lighthouse:

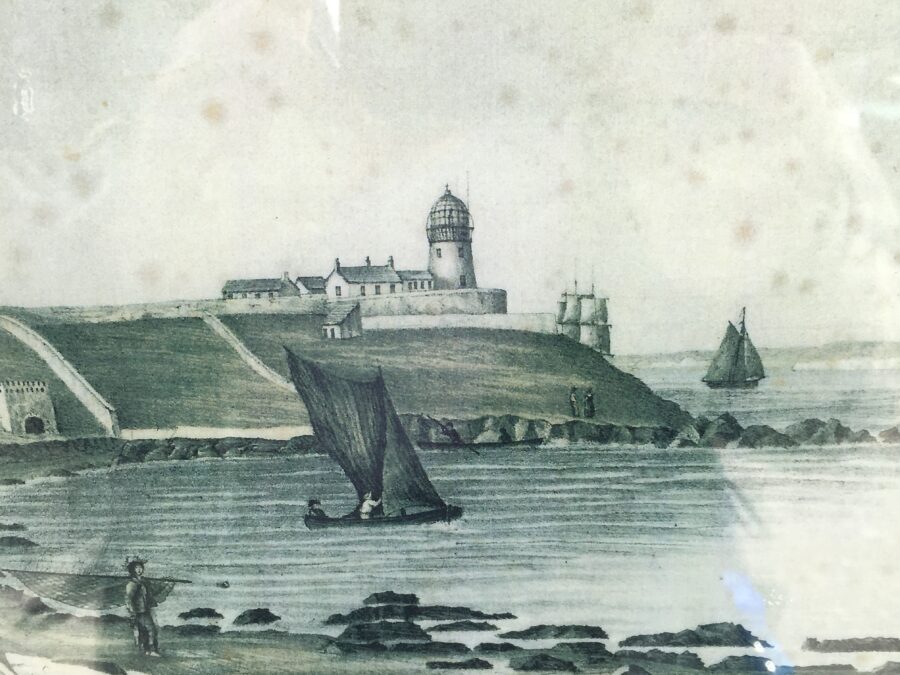

Around 1640-1650 AD, the Roche family purchased the Fitzgerald estate (approx 1500 acres) from Edmund Fitzgerald of Ballymaloe and lived for many centuries at Trabolgan. Roches Point at the mouth of Cork Harbour is named after this family. In post medieval times a tower existed on the estate called Roches Tower. In 1759, this tower was taken down.

A letter dated 28th August 1813 from Vice Admiral Thornborough of Trent, Cork Harbour, was read to the Ballast Board on 2 September 1813. In this letter he pointed out the danger of which vessels were put in frequenting Cork Harbour for want of a light house at the entrance to the harbour. This small lighthouse was working by June 1817 but its tower was not conducive to a major harbour of refuge and port, in 1835 it was replaced by the present larger tower.

The year 1864 coincided with further additions to the lighthouse. In September 1864, it was decided by the Ballast Office is Dublin that the lantern at Roche’s Point lighthouse be changed to a red revolving light, showing its “greatest brilliancy oncein every minute”. It came into effect on 1 December 1864. On the evening of 1 October 1864, a fixed white light was exhibited from the base of the lighthouse (a second light to the red one). This light was to shine towards seaward, between the bearings of S W by W and S W ½ S or between Robert’s Head and a distance of half a mile to the Eastward of Daunt’s Rock. Mariners were cautioned when approaching Cork Harbour by night to keep to the eastward of the limitations of the white light, until they had passed Daunt’s Rock. A fog bell was also erected which was to be sounded eight times in a minute during thick or foggy weather.

On 1 September 1876 two further improvements were made. The red revolving light in the lantern of Roche’s Point lighthouse was changed to an intermittent white light, showing bright for 16 seconds, and suddenly eclipsed for five seconds. This gave a brighter and more easily distinguishable light. The other improvement was the substitution of a larger fog bell hung from a belfry and sounded twice in a minute, for that which had hitherto bung at the basement of the light house, was sounded eight times per minute. The previous bell was of very little practical use as it could not be heard until a ship had got within the headlands. The new bell on the other hand, could be heard sooner, at a greater distance, and more distinctly.

In March 1888, new tenants were sought for the valuable plot of ground immediately adjacent the lighthouse complete with signal tower and four dwelling-houses, to be held for a long term at the yearly rent of £30. The houses had been availed of by the late owner as a commanding position offering means of communication with passing vessels.

By the early twentieth century, Roches Point had a fixed light 60 feet above high water with a visibility of 13 miles. It also has a recurring light, 98 feet, above high water, which can be seen fifteen miles away in clear weather.

By July 1970, Roches Point Lighthouse was all electric with a mandley generator to take over in case of ESB power failure. Formerly the light functioned by use of vaporised oil through a special type regenerative burner. The power of the light was also increased to being white 46,000 candelas and red 9,000 candelas.

By 30 March 1995 the presence of somebody physically watching out for mariners disappeared forever, at 11am when the three lighthouse keepers left the facility for good. The workings of the equipment became automated and were to be monitored from a lighthouse depot in Dun Laoghaire, Dublin. As to the foghorn the Commissioners for Irish Lighthouses decided that with modern shipping equipped with GPS navigation systems the foghorn, had become costly to maintain or replace, so it was no longer required.

Daunt’s Rock Light Ship:

Daunt’s Rock is between four and five miles south west of Roche’s Point and was named after a Captain Daunt whose British man-of-war ship hit the rocks and sank in the earlier part of the nineteenth century.

Up to 1865 it was beyond the limit assigned to the Harbour of Cork by the British Navy. It was not marked on the Admiralty Chart of Cork Harbour. In April 1864 following the smashing of the ship City of Cork upon the Rock, the Board of Trade strongly urged to remove the rock as soon as possible. They proposed that until its removal was implemented, to protect it by a lightship. Engineer Sir John Benson was requested to make an accurate survey of the rock.

By June 1865 a bell boat beacon was placed to mark the position of Daunt’s Rock. It was shaped like a boat and was surmounted by a triangular superstructure of angle iron and lattice work, which was coloured black, with the words “Daunt’s Rock” marked in white letters on it. The ball on the top of superstructure was 24 feet above the sea, and the beacon was moored within 120 fathoms SSW of the Rock and in 12 fathoms at low water spring tides.

In June 1974, The Irish Lights commissioners announced that they intended to withdraw the Daunt’s Rock lightvessel outside Cork Harbour and replace it with a high focal plane flashing buoy painted black and white. When the lightvessel was taken away in August 1974, radio beacons were established on the Old Head of Kinsale and at Ballycotton. The withdrawal followed the general pattern of Irish Lights policy. In the 1970s four lightships on the east coast of Ireland were replaced by flashing buoys.

Stories from Cork Docklands

The Cork Horns:

The earliest prehistoric artefact from Cork Docklands was discovered in reclamation deposits near the south jetties in the Victoria Road area of Cork city in 1909. When the excavations for a large tank had gone below river level and while the workmen were working in water, one of them brought up on his shovel a very slender metal cone. Later in the day two other similar cones, attached by metal to each other, were dug up at the same place. From a study of several of the old maps of Cork City, it is clear that in early times this particular area was a tidal salt marsh if not an actual mud flat. Some mud inside the horns resembled the grey mud of slobland along the river. Two of the cones were joined by metal to each other. It appears that the horns were in fact helmet ornaments and perhaps date from the Iron Age. The horns are now on public display in Cork Public Museum.

A Harbour of Shipwrecks:

There are over 400 shipwrecks in Cork Harbour ranging from seventeenth century galleons to twentieth century submarines. The locations of the majority of the 400 though are unrecorded. Ireland’s Underwater Archaeology Unit (UAU) was established within the National Monuments Service to manage and protect Ireland’s underwater cultural heritage. The Unit is engaged in the compilation of an inventory of shipwrecks recorded in Irish waters.

A Modern Port City:

The modern river port of Cork City began to take shape about the middle of the eighteenth century. Consolidation of the marshy islands provided building space and the covering over of the river channels and canals made wide streets possible. Quay walls were built at low water level and could not accommodate ships of moderately heavy burthen, which had to lighten cargo down the harbour for road transport to the city.

Cork Harbour Commissioners:

The formation of the Cork Harbour Commissioners in 1813 concentrated responsibility for the improvement and maintenance of the shipping channels and city’s quays into one organisation. During the following decades the Commissioners instigated an extensive programme of repairing and re-building the quays in limestone ashlar construction and this included the insertion of 8,000 timber toe-piles driven to depths of 21 feet in order to facilitate dredging close to the quays. The Commissioners spent a total of £34,389, raised from harbour fees, between 1827 and 1834 on the improvement of the city quays.

Once the quays were in a stable condition the river channels were extensively dredged and the extracted material was used to reclaim areas of slob-land, including the City Park area behind the Navigation Wall. Timber wharfs began to be constructed along a number of the quays in the second half of the nineteenth century, including Albert, Union, Victoria, St Patrick’s and Penrose Quays. In 1874 timber wharves were added to the south jetties. There were seven jetties constructed, each 43 ½ feet wide and initially separated by 120 feet of clear space which were subsequently filled in.

Early Twentieth Century:

During and up to the early years of the twentieth century berths were deepened at low water to keep all shipping afloat at lowest tides. Wharves and deep water quays were built and berths were deepened. In 1919 the Cork Harbour Commissioners acquired from the Board of Trade 153 acres of slobland at Tivoli for the purpose of pumping dredged material ashore, thus creating new land for industrial purposes. This happened over several decades. In the early 1950s oil storage depots were developed on the site. A further ten acres were made available for development circa 1960.

From 1960, modern Cork Harbour began to emerge, with the construction of oil terminals, steel mills, shipyards, deep water ferry port and industrial base. The entire concept of transporting general cargo underwent radical changes with the introduction of containerisation. That brought about revolutionary changes in ports. Whereas previously the only requirements of general cargo services were quays and adjoining transit sheds, the ports now had to provide quays with high load-bearing qualities and wide aprons, specialised container cranes, large marshalling areas for containers and further specialised handling machinery within the container compounds.

At Tivoli Industrial and Dock Estate new facilities included new container, roll-on roll-off and conventional berths, a 30-ton gantry-type container crane, a modern transit shed, a passenger terminal and office block and an extensive paved area for the marshalling of containers and commercial vehicles. Thirty-seven acres were allocated for general cargo purposes.

Cork was the first port in Ireland to set up a planning and development department. By 1972 this produced the Cork Harbour Development Plan in which a blueprint was designed for a future which would include sites such as that at Ringaskiddy, Little Island, and Cobh areas. By the middle of the present decade, employment in these industries is likely to exceed 5,000 people and the port’s frequent shipping services are an important factor in attracting new industries.

A Sociable Harbour

Royal Cork Yacht Club:

The Royal Cork Yacht Club (RCYC) traces its origins back to 1720. It began with the establishment, by six worthies of the time, of the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork, headquartered in the castle of Haulbowline Island. Membership was limited to twenty-five, and strict protocol governed all the club’s activities, both afloat and ashore. One rule, for example, ordered ‘that no boat presume to sail ahead of the Admiral, or depart the fleet without his orders, but may carry what sail he please to keep company’. Another forbade the Admiral to bring more than ‘two dozen (bottles of) wine to his treat’. The rules were applied with some rigour by the founding six members, who formed the club’s committee in 1720. One of the six was 24-year-old William, the 4th Earl of Inchiquin, and probably the first Admiral of the club.

The Victorious Goalers:

The Victorious Goalers of Carrigaline and Kilmoney is a rare Cork Harbour ballad, which tells of hurling games played long before the GAA came into being. On 17 December 1828, a local team from Carrigaline and Kilmoney defeated a team from the neighbouring parish of Shanbally-Ringaskiddy. Such matches were not infrequently organised by local landlords and in this case the team from Shanbally was led by William Connor, a naval officer of Ballybricken House (now demolished). The venue was Cope’s Field, a large field north-east of Carrigaline Castle. The ‘goal’, as the contest was termed (in Irish, baire), was conducted according to rules similar to the present GAA ones. There were eighteen to twenty players a side, the sliotar covered with stitched leather, an agreed referee, marked endlines and a change of sides at half time.

Royal Victoria Baths, Glenbrook:

The Royal Victoria Baths were opened in 1838. The Baths were tremendously popular with the people of Cork. The hot salt water was believed to be invigorating and a valuable treatment for rheumatism, lumbago and similar complaints. During the nineteenth century, the Baths were probably Cork’s most popular seaside resort. Towards the end of the century, other destinations further down the Harbour became increasingly accessible by river steamer and the Baths began to lose their popularity. They closed around the turn of the century and were derelict by 1929.

Bowling at Castlemary:

The sport of road bowling has a long connection with County Cork. A painting by Daniel McDonald from 1842 is entitled Bowling Match at Castlemary, Cloyne. It is the possession of the Crawford Municipal Art Gallery, Cork. It shows a mid-nineteenth century bowling match. The bowlers depicted are reputed to be Abraham Morris, a leading Cork businessman and Orangeman, and Montiford Longfield, likewise an Orangeman. This narrative is unusual as the participation of such establishment figures in bowling in the nineteenth century is a strange one. Local police viewed the game as dangerous on public roads and bowl players regularly found themselves in trouble with the law.

Queenstown, the Health Resort:

In the nineteenth century, Queenstown (now Cobh) was promoted as a health resort on account of its climate and location and was on par with Bournemouth in the south of England and Ventnor on the Isle of Wight. The promenade on the water’s edge was and still is a favourite place for locals and visitors to relax. The bandstand was originally built for the visit of Queen Victoria in August 1849. During the summer months regular band recitals take place there. The two cannons in the promenade were returned from the Boer and Crimean Wars in 1899 and 1854, respectively. Later in time, the promenade was named after US President John F Kennedy.

Ford Boxes and Holiday Homes:

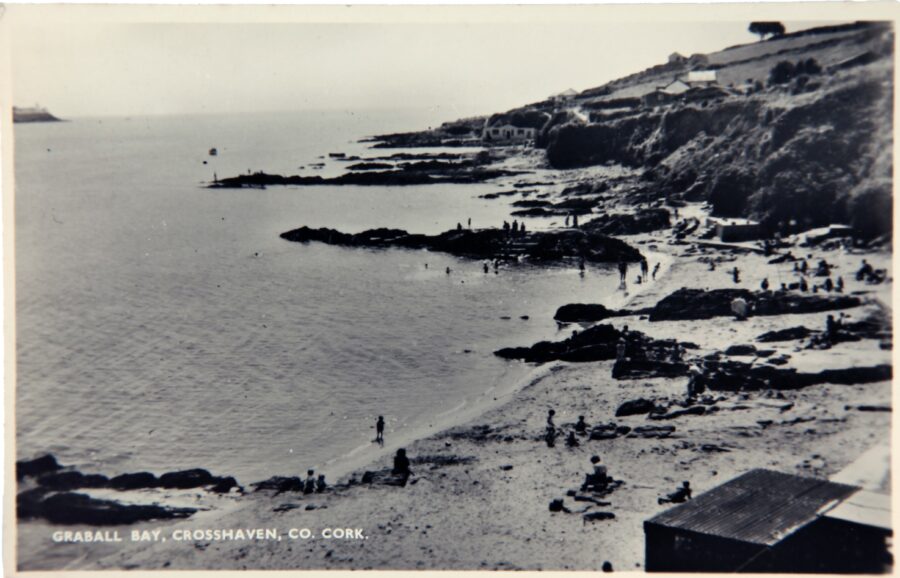

In the late 1800s, Crosshaven flourished from a quiet backwater into a tourism resort. The numerous bays like Graball Bay were unrivalled for bathing accommodation – even bathing dresses and towels could be attained. One media story records a local lady who erected two comfortable tents which could dine at least fifty people, and which were in constant demand. By the 1930s, the area had witnessed many light wooden holiday bungalows constructed by Cork’s citizens. Many were constructed from disused Ford delivery crates for cars in the mid twentieth century. Ford Boxes were salvaged from the Ford factory on The Marina and sold en mass after they had been used to ship motor parts over from Dagenham. Hard and enduring, the boxes became a marvel around Cork and were used as dog kennels, fowl houses, pigeon lofts, piggeries, flooring for trailers, boxes for storing grain, and even dancing platforms.

The Majorca Ballroom:

The big news of Thursday 30 May 1963 was the opening of a lavish new ballroom in Crosshaven. It was built on the most modern lines and was the brainchild of brothers Jer and Murt Lucey, who also owned the Redbarn Ballroom in Youghal, with a number of chalets and a fully equipped caravan park. There was to be dancing space for over 2,000 and the soft, subdued lighting and lush decor took quite a lot of thought and planning. One of the features of the ballroom was its revolving stage. The first to take the stage were Clipper Carlton and Michael O’Callaghan. The building and site of the Majorca ballroom was bought in July 1995. The building was dismantled and the site taken into enlarging the adjacent boat yard.

Buy The Little Book of Cork Harbour here: here: https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/publication/the-little-book-of-cork-harbour/9780750988056/