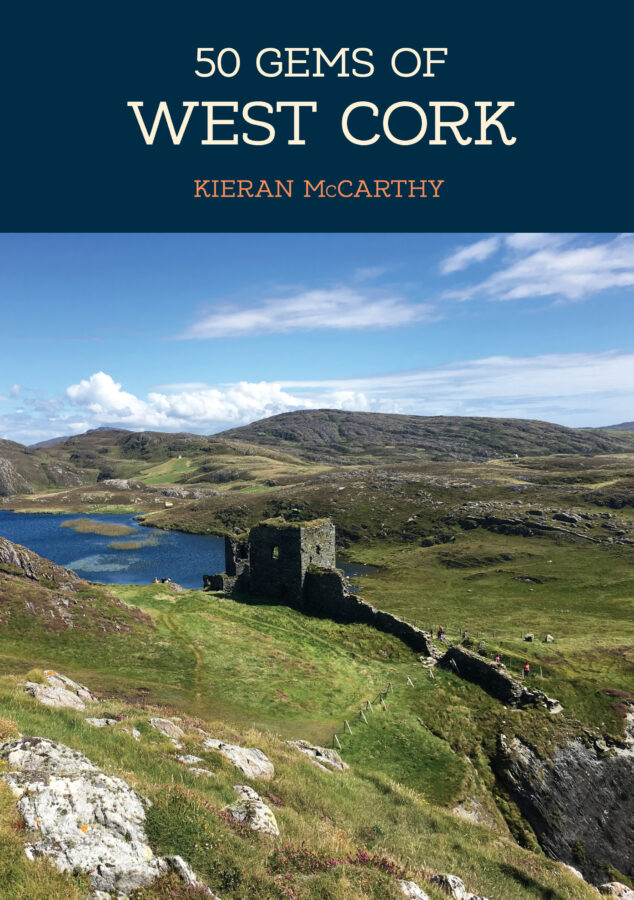

Abstract from 50 Gems of West Cork by Kieran McCarthy (2018, Amberley Publishing):

There were two words – raw and epic – which constantly came to mind as my 400cc scooter motorcycle traversed the roads and byways of West Cork whilst researching this new book in the past year. Both words came to mind as I felt almost swallowed up on my small bike disappearing on routeways, which duck and weave through hollowed out rock scarred by glaciation movements 20,000 years ago or parked up on coastal beaches where the folding of the rock can be seen from near the origins of the universe.

My book, 50 gems of West Cork, builds on a previous publication called West Cork Through Time (Amberley Publishing 2015), which explored the fascination by post card makers one hundred years ago of West Cork in its scenery, its culture and its people. This new book returns to some of those sites chosen and details new ones exploring how these key sites became the focus of attention and development – and how their stories, memories and the making of new narratives were articulated in an attempt to preserve an identity and/ or communities locally and nationally at sites or to create new identities and communities.

Several sites in this book came into being in the fledging years of the Irish Free State where tourism and story-telling about the nation’s history were highlighted or some sites were created from the burgeoning boom time of 1960s Ireland, where the focus was on developing industry and recreational amenities. For example, the promotion of areas such as Inchidoney Island for more tourism was driven by the Irish Free State’s Irish Tourist Association (ITA), which was established in 1925 to market the young Irish Free State as a tourist destination internationally. Small resorts along the West Cork coastline were developed simultaneously at sites such as Courtmacsherry, Glandore, Bantry Bay, Glengarriff and Berehaven.

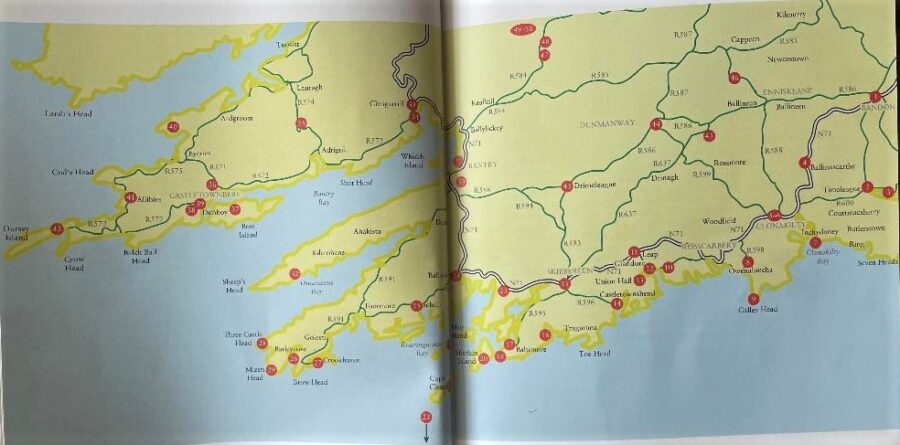

The title book explores 50 well-known gems of the West Cork region. It brings their stories together in an accessible manner. It is not meant to provide be a full history of a site but perhaps does try to provide new lenses on how heritage is looked at and the power of narrative construction and collective memory in West Cork. The book takes the reader from Bandon to Dursey Island, from Gougane Barra to the Healy Pass.

Researching West Cork, the visitor discovers that each parish has its own local historian, historical society, village council, sometimes a library, tidy towns group, community group and business community who have inspired the collection of stories, the creation of heritage trails and information panels, and the championing of a strong sense of place and identity. Relics from the past also haunt the landscape with prominent landmarks ranging from Bronze Age standing stones to ivy clad ruined houses and castles, churches and old big houses, to beacons, cable cars and lighthouses. All add to the narrative of the spectacle that is West Cork.

The origins of the beautiful towns of the West Cork can vary from medieval times to the early twentieth century. On walking around them what is particularly impressive is the nineteenth century fabric, which make for very photogenic spaces to capture. There are old and colourful shopfronts, old narrow laneways and streets, ornate water pumps, cobbled surfaces, historic market places, eye catching churches as well as two hundred year-old bridges and older bridges. These latter traits define the look of and layer with stories much of West Cork’s towns. For example, on a sunny day as the sun sets, the colourful shopfronts of Bandon’s Main Street with its stone-built fabric bridge are illuminated.

Where much is written down and attempts made at compiling local histories in West Cork, there is a need to compile the macro historical picture of West Cork. Certainly, the work of Fáilte Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way has been key in bringing many threads of stories together, kickstarting long forgotten traditions and empowering communities to present their story to the visitor. In particular, this book draws on the brilliant Irish Newspaper Archive where the past editions of the Cork Examiner and the Southern Star are digitised and provide much information at different points of a site’s evolution. With a building, statue or a view, looking closely at the human detail can reveal nuances about how places are seen and understood and ultimately can be championed going forward into the future.

In all, this book comprises a myriad of stories of different shapes, patterns and colours just like a painter’s palette of colours. Every site or gem presented is charged with that emotional sense of nostalgia – the past shaping and inspiring present thoughts, ideas and actions. However, this book only scratches the surface of what this region has to offer. West Cork in itself is a way of life where generations, individuals and communities, have etched out their lives. It is a place of discovery, of inspiration, a place of peace and contemplation, and a place to find oneself in the world. What’s the best way to see West Cork – travel through it, sense it and enjoy it!

Abstracts of Gems

Gem 2, The Lure of the Past – Timoleague Franciscan Abbey:

The lure of the ruinous Timoleague Abbey is too difficult to resist. Here one enters a maze of stone walled rooms and headstone emerging from the ground from all angles. The abbey is a remnant of the early phase of Old English colonisation and remains one of the most impressive ruins of an Abbey in the south of Ireland.

Following the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169 large parts of Ireland were colonised. Anglo-Norman families such as the Barry’s and the Hodnetts settled in this area and their surnames and placenames survive to the present day. In the thirteenth century, a great battle was fought at Timoleague between the Hodnetts and the Barrys. Lord Philip Hodnett, the leader of the Hodnetts, was killed, and Irishmen routed by the Barrys, under Lord Barrymore.: The latter and His descendants then became the owners of Barryroe and the district around Timoleague.A member of the Hodnetts became Gaelicised and began to use the Irish form “Seafraidh”. Their descendants became MacSeafraidh and from their court or castle, the name Cúirt Mhic Sheafraidh or anglicised Courtmacsherry came into being.

Local folklore and secondary historical account show a range of dates for the foundation of Timoleague Abbey, but it looks like it was at least founded between 1240 and 1316AD by either Donal Glas MacCarthy or William de Barry. St Mologa, after whom the abbey was called, was a native of Fermoy district in the seventh century AD.

View “Exploring Timoleague Abbey” by Kieran McCarthy

Gem 6, The Landscapes of a Statesman – Remembering Michael Collins

The first ever commemoration at Béal na Bláth took place 12 months after Michael Collins death. On 21 June 1923 Richard Mulcahy led Irish Free State troops in erecting a small wooden cross. Floral wreaths were laid, mass was delivered by an army chaplain and Mulcahy gave a short oration. A year later on 23 August 1924 another ceremony led by General Eoin O’Duffy and Chairman of the Free State government, W T Cosgrave unveiled a large limestone one to replace the wooden cross. As the years progressed this minor road of which the memorial stands was slowly widened complete with platform to accommodate an annual oration to the site of Irish history’s most infamous ambush.

In 1964 a site has been acquired at Sam’s Cross, Clonakilty, for the erection of a memorial to Michael Collins. A ten-ton granite stone from the Wicklow mountains formed the memorial. A bronze plaque showing a profile of Collins is set into the face of the slab. The plaque was designed by the Cork sculptor, Mr Seamus Murphy RHA who had already completed a bust of Michael. It was unveiled on Sunday 18 April 1965 by Tom Barry. Nearby the ruins of the foundations of the Collins family house can be visited. In October 1990, the Michael Collins Centre just off the Clonakilty-Timoleague was opened as a visitor centre.

In 2002 the first statue of Michael Collins was unveiled at the edge of Emmet Square in Clonakilty. The project was led by Tim and Dolores Crowley of the Michael Collins Centre and members of Clonakilty Historical Society. The sculptor Kevin Holland was commissioned to create a seven-foot bronze statue. More recently in 2016, the Michael Collins House opened in Clonakilty which is a new museum dedicated to the life and times of Michael.

Gem 10, A Compass in the Landscape – Drombeg Stone Circle:

Drombeg is one of Ireland’s most famous stone circles and is also part of suite of circles and standing stones in West Cork. It is also one of the most publicly accessible. On the winter solstice on 21 December each year, the sun sets over the recumbent stone on the stone circle. If you stand looking between the two portal stones, you will view the sun set in a notch in the opposite hill and over the recumbent stone which is diametrically across from the two portal stones.

Drombeg was one of the earliest ancient sites protected by National Monument Act, 1930. It was added to list of protected structures by the State in 1938. However, a glance through the Archaeological Inventory of West Cork reveals a myriad of ancient standing stones, stone circles and fulacht fia (ancient cooking sites) – all very much present in the heritage DNA of the region.

The Drombeg Stone Circle complex is located on natural rock terrace on the southern slope of a low hill. The circle was excavated 1957 and the nearby fulacht fiadh and hut site was excavated in 1958. The circle comprises seventeen stones; two missing and one fallen. Five pits were uncovered within the circle, sealed beneath compacted gravel floor; one pit contained deposit of cremated human bone, fragments of shale and numerous sherds of coarse fabric pot. Other finds from circle included seven pieces of flint and small convex scraper.

The excavator of the site and archaeologist Edward Fahy literally put Drombeg on the map as the findings drew much media attention and were published in the eminent Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society. It was one of Edward’s first excavations. Up to then he had been a student at the Cork School of Art. He worked with Michael J O’Kelly, the curator of Cork Public Museum in Fitzgerald’s Park especially in designing the cases for display when the museum officially opened on 4 April 1945. The building up of the Museum’s collections and displays was a continuing effort and while engaged in that work, he studied for and was awarded with distinction the Diploma of the Museums Association. This required the writing of a dissertation coupled with specialised courses and examinations in England.

Subsequently Edward Fahy pursued a BA degree, which he obtained with first class honours in Archaeology and Geography. He took part in many of Michael J O’Kelly’s excavations at this time and built up his experience in fieldwork and excavation techniques.

Gem 18, A Coastal Pillar, Baltimore Beacon:

Outside Baltimore atop a cliff face is the unique Baltimore Beacon, which offers scenic views over Baltimore Harbour and Sherkin Island. The impressive conical white painted Baltimore Beacon, sometimes called the ‘pillar of salt’ or ‘Lott’s wife’ is approximately fifty feet (15.2m) high and fifteen feet (4.6m) in diameter at the base. Towards the end of July 1847, Commander James Wolfe, Royal Navy, informed the Ballast Board that he had recently completed a survey of Baltimore Harbour and noticed the destruction of the warning of rocks beacon on the eastern point of the southern entrance to the harbour. Almost a year passed, when on 6 July 1848, the Board requested the secretary to seek permission from Lord Carbery for a piece of ground thirty feet in diameter, on which to build a new Beacon. The Cork Examiner on 16 September 1859 (p.3) records:

“The bay or harbour of Baltimore, through which the journey lies, is admirable as a station for ships, and is most attractive in its picturesque grandeur. It has almost uniformly deep water in the basin and debouches on the sea through an opening of less than the width of our Harbour’s Mouth, formed on the right side by Sherkin island, and on the left by the mainland. On either side rise precipitously stupendous cliffs, the highest of which on the left is crowned by a tall tower or beacon, which may be seen at immense distances seaward”.

In recent times, the hosting of an interactive map online was developed to facilitate easy access to the Wreck Inventory of Ireland Database compiled by the Department’s National Monuments Service. At the base of the Baltimore’s Beacon’s cliff lies a green buoy which marks a reef where a Man O’War Ship, called the HMS Looe, was grounded in 1697 (and which in time gave its name to the reef). Built only a year earlier in Plymouth in 1696, the 32-gun or ‘demi-batterie’ frigate was the flagship of the Irish Coast Fleet assigned to patrolling the waters around Ireland. The ship was one of only 34 such ships constructed at the time. On stopping at Baltimore for provisions, on leaving the harbour mouth, stormy weather grounded the ship on reef. The crew managed to escape the sinking vessels and to save much of its tackle and cargo.

In 2001 the Underwater Archaeology Unit (UAU) of the National Monuments Service executed a survey of the wreck site. No structural evidence was found but seven iron guns and numerous cannon balls were discovered at various depths on the reef and on the sea floor.

View Kieran’s “Exploring Baltimore Beacon”:

Gem 21, Snippets in Time – Cape Clear Museum:

Beyond the church ruins and St Ciarán’s Well, a pathway extends up Cape Clear Island’s steep hills. The community museum lies high up on the ridges of Cape Clear Island. The building was originally a national school for girls but now is filled with local history snippets, folklore, old pictures and artefacts from decades previously. Information inside the buildings relates that the old school building was abandoned in 1897 when a new school house was constructed elsewhere near the South Harbour.

In 1970 work commenced on the restoration of the old school building under the direction of an tÁth, Tomás Ó Murchú, the island curate at that time. With the help of Na Campaí Oibre (the work-camp movement) and islanders, the old ruin was for the most part rebuilt and reroofed. Groups of voluntary workers from Cork and elsewhere continued to help with the restoration. Roinn na Gaeltachta and AnCo / FÁS provided funding and training.

In 1979, the building was first used as a museum and exhibition centre under the direction of Éamon Lankford. In 1981, a Museum Society, Cumann Iarsmalann Chléire was formed to source, collect and exhibit artifacts of island interest and develop an archive which would comprehensively detail the history, culture, and heritage of the island. The centre is open daily during the months of June, July and August and can be visited at other times (Winter/Spring) by arrangement with the Information Bureau at Trá Chiaráin.

View “Exploring Cape Clear Island, Co. Cork” by Kieran McCarthy:

Gem 28, Upon the Ramparts of Ruins – Three Castle Head:

Located on a western headland above the Mizen Head is what is known as Three Castle Head. Spectacular in its location, Dun Locha or Dunlough or Fort of the Lake sits atop the brink of a 100-metre cliff face on the site of an ancient promontory fort. In its day it was an important strategic location with 360 degree views of the landscape. Historical information signs on the approach to the castle point to an annal record that it was constructed by Donagh O’Mahony in 1207. He is reputed be a scholar and traveller on pilgrimages to the Holy Land. Archaeologists have also noted that the extant ruins are more fifteenth century in date and possibly were added to an earlier structure.

According to the Archaeological Inventory of West Cork, the castle’s location is all about creating maximum defence. The three towers of this edifice are connected by a rampart wall of some 20 feet in height, one of the highest medieval walls still intact in Ireland. Walls extend from the edge of the cliff eastwards to the lake. Dry stone masonry was used in its construction. The geology of the area is metamorphic, which supplied relatively flat and regular stone. Quarried from nearby, the stones were not cut but utilised as they were.

Tower number one by the lake was three stories high, with a main arched entrance. Tower number two was of a similar height, also with a spiral staircase, and has an interior archway at ground level that led either to a separate room below or was the entrance to a souterrain leading to the sea, utilising the natural crevices in the rock. The third tower or the tallest tower, 10-15 metres in height, also had three stories. Within its space, the ground floor had several loophole windows. Above the second level are two arches, which support a stone ceiling. It had uppermost ramparts for observation and defence.

There are 40 acres behind the castle known as the Island to explore as well. On foot it is rough terrain but the visitor is met with spectacular views of the Mizen Peninsula and the Beara Peninsula.

View Kieran’s “Exploring Dunlough Castle, Three Castle Head, Co. Cork:

Gem 30, A Chequered Past – Bantry House:

The elegant Bantry House defines the character of the adjacent local town. The house inspired the town’s development and the pier and vice-versa. The Archaeological Inventory of West Cork presents research excavations carried out in 2001 in an area directly west of the present house. Here the remains of a site were discovered of a deserted Gaelic medieval village and a seventeenth-century English settlement. Excavations revealed the foundations of the gable end of a mid-seventeenth-century house. This was in turn overlain by a more substantial and better-built rectangular structure, interpreted as a timber-built English administrative building. A palisade trench, dug late in the sixteenth or early in the eighteenth century, immediately pre-dated this building. According to the excavator, this had presumably created a stockade foundation around the early plantation settlement. Sixteenth-century cultivation ridges were also uncovered. These had cut into the foundations of a fifteenth/ sixteenth-century Gaelic domestic structure.

The area seems to have been abandoned in the middle of the seventeenth century and all available cartographic and documentary evidence indicated that no subsequent building or landscaping had taken place. The narrative of the old sites fell out of memory.

The earliest records for the next phase of the site date from circa 1690 and describe land deals between Richard White and the Earl of Anglesey, which established the basis of the Bantry House Estate. The records, which are in the archives of the library of University College Cork, include information about the ownership of land and property on the family’s Bantry, Glengarriff, Castletownbere and Macroom estates. The Whites built a detached five-bay two-storey country house over a basement, circa 1710.

In 1816, Richard White was created first Earl of Bantry. Prior to his marriage, he toured extensively on the continent, making sketches of landscapes, vistas, houses and furnishings, which he later used as inspiration in expanding and refurbishing Bantry House. The White family throughout the nineteenth century intermarried with other well-known landed families including the Herberts of Muckross House, Killarney, and the Guinness family of Dublin. Inspired by his travels and contacts, in 1820 Richard invested in the construction of new six bay two bow ended additions to the old country house as well as adding elaborate landscaped gardens complete with outbuildings, stables and gate lodges. In 1845 new bow-ended wings were also added.

William White, the 4th and last Earl of Bantry, died in 1891. Ownership of the estate then passed to his nephew, Edward Leigh, who assumed the additional name of White in 1897. His daughter, Clodagh, inherited Bantry House and estates on the death of her father in 1920, and in 1927, she married Geoffrey Shellswell, who assumed the additional name of White. Clodagh Shellswell-White died in 1978 and the ownership of the house and estate passed on to her son, Egerton Shellswell-White. Today the house and gardens still belong to the White Family and are open to the public to explore and engage with.

Gem 31, An Expedition into the Past – Stories from Bantry Bay:

Information panels on Bantry’s town square champion Ireland’s nationalist past and define the layout of the square and which history a visitor engages with first. The panels describe the collective memory of the campaign of Theobald Wolfe Tone in the interests of the United Irishmen and their quest for independence of this country. He journeyed to Paris at the beginning of the year 1796 to court the French to help with rebellion against the British in Ireland. There he met General Hoche, the brilliant French commander. On 16 December a fleet of 44 vessels and 15,000 men under General Hoche and Admiral Morard-de-Galles set sail from Brest.

The expedition was ill-fated from the start; for it was but a day at sea when the frigate Fraternite carrying Hoche and Morard-de-Galles, got separated from its companions and never reached the Irish shore. A dense fog arose, and Bouvet, the Admiral-in-Command, found he had only eighteen sailing ships in his company. Two days later, however, he had 33, and he steered direct for Cape Clear Island. Land was sighted on the 21 December, and though a rough easterly breeze was blowing, 16 vessels succeeded in reaching Bantry Bay. Twenty ships remained outside battling hopelessly against the gale and were eventually driven off the coast. A landing was impossible and Wolfe Tone, aboard the gunship Indompitable spent his cold Christmas on the Bay. On the night of 25 December an order came from Bouvet to quit the assault and put to sea. It was decided to land in the Shannon Estuary, but rough weather was increasing. The squadron put to sea and returned to France. It was the 27 December and the end of the Bantry Bay Expedition. Of the 48 ships that left Brest on 16 December 1796, only 36 returned to France. The rest were either captured by the English Navy or wrecked.

The ship La Surveillante was considered unseaworthy for the return journey and was scuttled by its crew in Bantry Bay. Its crew and all 600 cavalry and troops on board were transferred safely to other French ships in the fleet. According to the National Wreck Inventory, the three masted La Surveillante was built in Lorient in 1778 and carried 32 guns. The vessel had successful naval engagements with British warships during the period of the American War of Independence (1775–82). The wreck of La Surveillante was discovered in 1981 during seabed clearance operations following the Betelgeuse oil tanker disaster. One of La Surveillante’s anchors was trawled up by fishermen and put on display in Bantry. In 1987 two 12-pound cannons were raised from the wreck, and in 1997 the ship’s bell was lifted, which is now currently on display in Bantry Armada Centre, at Bantry House.

Gem 35, The Border of Counties – The Healy Pass:

Almost immediately after crossing the bridge spanning the Adrigole River at Adrigole, the coast road merges with one sweeping down from the north-west, which seems to delve into the very core of the tremendous mountains whose peaks soar above one another. The road weaves out “S” hooks and scissors and horse-shoe bends as it climbs ever upwards to the Healy Pass, which marks the Cork-Kerry border.

The Pass was also the route by which live-stock were conveyed, particularly cattle to and from the Kenmare fair. For a long period, it was a mere track beaten out by those following the line of least resistance, and thus, invariably, was identical with the course of mountain torrents, as water always manages to percolate through the easy passages. From time immemorial it was the way used by the local people. Through it the dead were carried on their last journey to the home of their birth. The place where the coffins were rested after the arduous climb while those engaged prepared for the even more perilous descent.

In the closing years of 1890s decade and the early decade of the twentieth century, Mr Tim Healy who was then one of the Irish representatives in the English Parliament at Westminster, fought to have something done to render the pass more passable for the inhabitants on this side of the peninsula. He was, however, thwarted at every turn by powerful vested interests, keen on the preservation of the amenities of certain residential estates on the Cork-Kerry border, which, it was believed, would be impaired if the right of way were put into more frequent use.

Under the Irish Free State he did not forget his pet project, and eventually he succeeded in getting the then Minister for Local Government and Public Health, General Richard Mulcahy, to put the long-deferred project into execution. A sum of £7,000 was advanced for the purpose and work began in 1931. Making every allowance for the advance in engineering knowledge and skill and the up-to-date equipment, it was nevertheless a herculean task. A makeshift roadway existed as far as the point where the rise began, but from that onwards it was practically virgin country. In 1932 the feat was accomplished. Operations were continued down the other side for a distance of a mile and a half into County Kerry until contact was established with an existing road there.

Before leaving Healy’s Pass mention must be made of the magnificent wayside Calvary which was unveiled in early June 1935. Made of marble, it is sheltered in a niche within a few yards the highest point of the roadway. It was the gift of a Cork City donor, who wished to remain anonymous it is of marble and fittingly occupies a most commanding position.

View Kieran’s “Exploring The Healy Pass”:

Gem 40, The Shaper of the Land – The Hag of Beara:

Indented by an exposed coastline and defined by the Slieve Mikish and Caha Mountains, the Beara Peninsula is some 45 kilometres long and 15 kilometres wide at its widest point. The principal point in the Caha Range, Hungry Hill stands 2,251 feet and is well known to tourists not only for its mountain lakes and lofty waterfall, but also for the superb view which it affords.

Prehistoric settlers were attracted to the area as evidenced by standing stones, stone circles, and wedge tombs. Rich folklore embedded into the local landscape survives of giants, Spanish princesses and witch-like creatures. The geomorphology of Coulagh Bay is attributed to a pair of fighting giants called the formorians According to folklore the name Beara is that of a Spanish princess, the wife of Eoghan Mór (the mythical second century BC King of Munster). Later Christian tradition pitches the presence of a Celtic Goddess of Harvest, Shaper and Protectoress of the Land – An Chaileach Bhearra or translated the Hag of Beara. In truth, she represents many cultural meanings such as mother and fertility Goddess and Divine Hag. She was deemed a goddess of sovereignty, who gave the kings the right to rule their lands

According to the local information sign, the Hag of Beara is associated with Kilcatherine in the northern part of the Peninsula, north of Eyeries, overlooking Coulagh Bay. According to myth, The Hag lived for seven periods of youth one after another – so that every man who co-habited with her came to die of old age. Her grandsons and great grandsons were so many that they were made up of entire tribes and races – hence her legend is woven into folklore across several parts of Ireland and across the west coast of Scotland.

The advent of the arrival of Saint Caitiarin and Christianity was deemed a threat to her powers. Local folklore has it that one day after collecting seawood along the shore of Whiddy Island, the Hag on her return encountered the priest asleep on a local hillock. She drew near to him and quietly took his prayer book and ran off. A cripple who lived nearby on seeing what happened shouted at the saint who awoke startled and the saw the hag running off. The saint caught up with her, re-acquired the prayer book and turned her into a grey pillar stone with her back to the hill and her face to the sea.

Visiting the pillar stone today, the visitor can see offerings of coins and pebbles. The first extant written mention of the hag is in the twelfth century Vision of Mac Conglinne, in which she is named as the “White Nun of Beare”.

The myth of the Hag is harnessed as a construct in forging a national and cultural identity in the early twentieth century. She is mentioned in work by Irish academic, scholar of the Irish language, politician and Douglas Hyde in 1901 and in verse by writer, republican political activist and revolutionary Pádraig Pearse “Mise Éire Siné mé ná an Cailleach Béara”. In most recent years, the myth of the Hag has been spotlighted again by well-known Irish poet Leanne O’Sullivan.

View Kieran’s “Exploring The Hag of Beara”:

Gem 45, A Personalised Past – Ballinacarriga Castle:

There are also Instruments of the Passion, and figures which may represent St John, Blessed Virgin and St Paul as well as decorative panels. On the first floor, there are carvings of a figure and five rosettes said to represent Catherine O’Cullane and her children. On the third floor are carvings, which include the inscription “1585 R.M.C.C.” (Randal Muirhily [Hurley] and his wife Catherine O Cullane).

On the external face of the eastern wall of the castle is inserted a carved stone, bearing a representation of a grotesque stone carved figure known as a Sheela-na gig. Sheela na gigs are figurative carvings of naked women exhibiting an embellished vulva. They are architectural grotesques found all over Europe on castles, cathedrals, and other buildings. The highest concentrations can be found in Ireland, Great Britain, France and Spain, sometimes together with male figures. Ireland has the greatest number of surviving Sheela-na-gig carvings. There are circa 165 recorded extant examples in Ireland. The carvings could have been utilised to protect against demons, death and evil. They are often positioned over doors or windows, presumably to protect these openings.

The Ballabuidhe Horse Fair dates back to 1615, when a Charter for it was granted by King James 1 to Randal Óg Hurley of the castle. The fair is steeped in history, tradition and antiquity. It is still one of Ireland’s greatest annual horse fairs, to be held on the streets, and where buyers come from all over Ireland and Cross-Channel too.

Gem 46, Of Saints and Scholars – Kinneigh Round Tower:

The town land of Kinneigh is situated three miles north-west of Enniskeane and just south of Coppeen. The area is blessed with strong historical societies and local historians, whose writings have survived going back over 100 years and have covered many historical gems. One such ancient site, which as a topic has been pursued at length is the local ancient monastery of Kinneigh. According to the Annals of Cork a See was founded here in 611AD by St Colman, and the Four Masters record the death of Abbot Forbasach in 850AD. The monastery was beautifully situated on the gentle slope of a hill, being sheltered from the north and east winds. The meaning of the word Kinneigh is uncertain. Some writers in the past record Ceann Eich as meaning horse’s head and may connect to the resemblance of the hill to the head of that animal. There is now no hill or rock in the district to support this derivation,

In the tenth century, the old monastery at Kinneigh was abandoned. It appears that the monks, for strategic reasons, selected Sleenoge half-a-mile to the east, as the place for their new home. There is no reference to buildings which they erected here except to the round tower, which was constructed in 1014.

There is a remarkable similarity in the size of round towers. Most of them, have a circumference at the base of about 1,5 metres while the wall is a metre thick. The position and scale of the doors, windows and storeys also follow broadly similar patterns.

The tower is one of only two round towers in County Cork (the other in Cloyne in East Cork) and is one of 73 structures in Ireland. Many round towers were described as ecclesiastical bell towers and storage spaces.

Built in 1856, St Bartholomew’s Church of Ireland is built on the site of an ancient monastery of which the imposing round tower is the only upstanding remains. The church is the third church on the site. The extant one was built in the Romanesque style and displays finely crafted window and door surrounds. The community used the round tower as a bell tower.

View Kieran’s “Exploring Kinneigh Round Tower”:

BUY 50 Gems of West Cork here, https://www.amberley-books.com/50-gems-of-west-cork.html

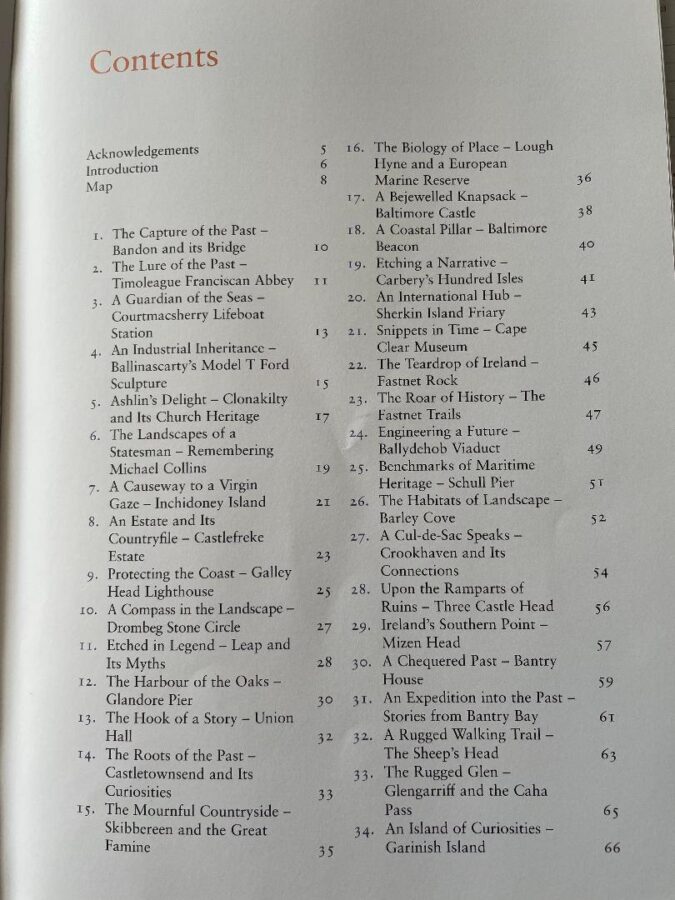

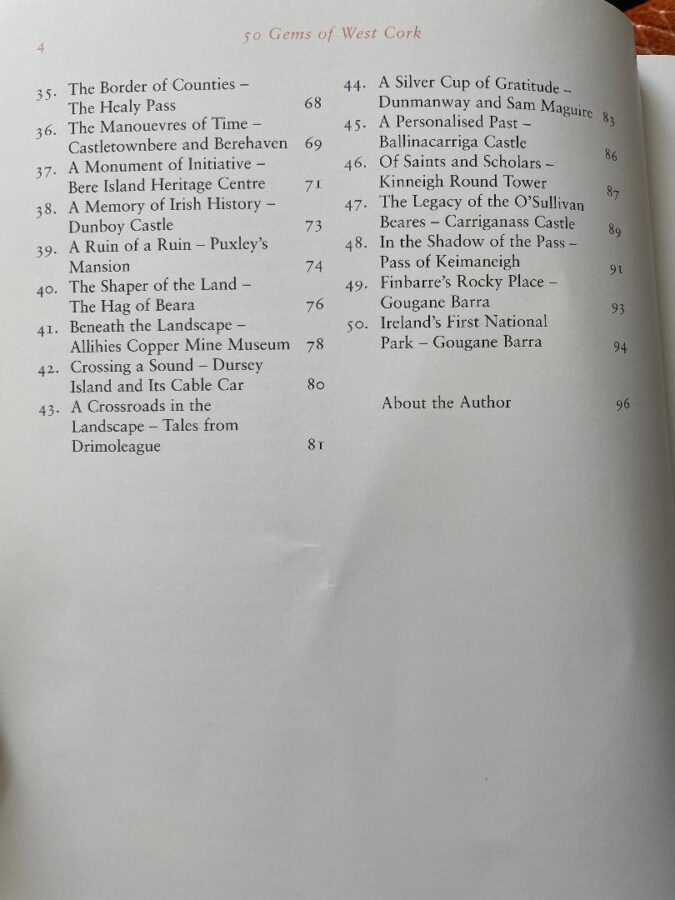

50 Gems of West Cork Contents Pages: