Some Figures:

- The biggest conflagration in Cork in 300 years.

- Nearly 100 businesses and homes were destroyed or badly damaged by fire and looting.

- A huge photographic record of the destruction survives in local newspapers such as the Cork Examiner plus in international news – many records survive in our Library, Museum and Archive, plus told in St Peter’s Church, heritage centre.

- Familiar landmark buildings were gone forever- whole buildings had collapsed or a solitary wall had survived.

- City Hall and Carnegie Library destroyed.

- Five acres of property had been destroyed, over 2,000 people had lost their jobs, and an estimated 3 million pounds of damage – or circa e100m in today’s world.

- Streets ran with sooty water, strewn with broken glass, strong sense of burning.

– Listen to Kieran’s December 2020 Interview with The Business, RTE Radio 1,

RTÉ Radio Player (rte.ie)

– Watch original footage of the Burning of Cork Film: Irelands Agony – IFI Player – footage produced by Topical Film Company (1920)

– Watch Burning of Cork Centenary commemoration, Friday 11 December 2020:

It Starts at Dillion’s Cross, 7.30pm:

It was a night like no other in Cork’s War of Independence. The Cork Examiner records that about 7.30pm on Saturday night, 11 December 1920 auxiliary police were ambushed near Dillion’s Cross on the way to Cork Barracks. Bombs were thrown at the lorry and several of the occupants were injured, some badly. Reprisals began in the locality of the ambush, and during the night several houses in the district were burned. Buttimer’s Shop and Brian Dillion house were targeted. The latter House, which had a tablet on it dedicated to Irish Fenian Brian Dillion, was completely gutted. Rifle shots rang out and the crackling burning of timber was heard.

Gunfire in St Luke’s Area, 8pm-10pm:

Between 8pm and 10pm volleys of revenge gunfire from auxiliary police and Black and Tans reverberated through the flat of the city and created considerable alarm as people stampeded away in various directions. Many people elected to stay in hotels and others sought the hospitable shelter of friend’s houses in the neighbourhood in which they happened at the time. The people sought their homes, extinguished all lights, and then passed through many hours of fear.

Passengers on the last tram to St Luke’s Cross, which left the Statue at 9pm had an eventful journey. The car had got about 60 to 70 yards beyond Empress Place Police Station on Summerhill North when a number of armed men in police uniform carrying carbines, and accompanied by auxiliaries, held it up. They ordered all the passengers off at the point with revolvers. Male passengers were ordered to line up for searching. Some tried to run and a voice rang out, “I’ll shoot anyone who runs”. Shots were fired in the air while the searches were being conducted.

The tram car was smashed up and was brought back by the conductor to the Fr Mathew Statue, who at that point was ordered off. It was set on fire and completely destroyed.

Gunfire on St Patrick’s Street, 10pm:

It was hoped that when curfew hour was reached there would be cessation of the firing and explosions, but such hopes were not realised: in fact as the night advanced the situation became more terrifying, and the people especially women and children were rendered helpless amidst fire and shots by Black and Tans stalking the streets with rifles and revolvers. About 10pm, following explosions, Messrs Grants’ Emporium, in St Patrick’s Street, was found to be ablaze.

Grants Emporium Set on Fire, 10.30pm:

The Superintendent of the City of Cork Fire Brigade, Alfred Hutson, received a call at 10.30pm to extinguish the fire at Grants. He found that the fire had gained considerable headway and the flames were coming through the roof. He got three lines of hose to work—one in Mutton Lane and two in Market Lane, intersecting passages on either side of these premises. With a good supply of water they were successful in confining the fire to Grant’s and prevented its spread to that portion running to the Grand Parade from Mutton Lane, while they saved, except with slight damage, the adjacent premises of Messrs Hackett (jeweller) and Haynes (jeweller).

The Market – a building mostly of timber – to the rear of Grants was found to be in great danger. Except for only a few minor outbreaks in the roof the fire brigade was successful in saving the Market and other valuable premises in Mutton Lane. The splendid building of Grant’s though with its stock was reduced to ruins.

Munster Arcade Set on Fire, 11.30pm:

During the fire-fighting at Grants Alfred Hutson received word from the Town Clerk that the Munster Arcade was on fire, just some doors from where he was. This was about 11.30pm. He sent some of his men and appliances available to contend with it. Shortly after he got word that the Cash’s premises were on fire. He shortened down hoses at Mutton Lane and sent all available stand-pipes, hoses and men to contend with this fire as well.

Hutson’s men found both the Munster Arcade and Cash’s well alight from end to end, with no prospect of saving either, and the fire spreading rapidly to adjoining properties. All the hydrants and mains that they could possibly use were brought to bear upon the flames and points were selected where the fire may be possibly checked and their efforts concentrated there.

The Spreading of the Fires, 12-6am:

The flames ranged with great intensity, and within an hour, buildings were reduced to ruins. Owing to the inflammatory nature of the materials in these premises, or as the result of petrol having been sprinkled within the buildings, the conflagrations became most fierce and the blocks of buildings running between St Patrick’s Street and Oliver Plunkett Street on one side and Cook Street and Merchant street on the other side became involved. It was impossible to subdue such outbreaks.

The Shooting of the Delaney Brothers, 2.50am:

In the early hours of Sunday morning at 2.50am in the upper end of Dublin Hill in Blackpool the Black and Tans encroached on the houses of the Delaney family. IRA members Joseph Delaney, aged about 24, was shot dead and his brother, 30-year old Cornelius and his 50 year old uncle, William Dunlea, were wounded, the former very dangerously. All were shot at point blank range by uniformed soldiers. The two wounded men were removed to the Mercy Hospital where Cornelius succumbed to his wounds.

City Hall and Cork Carnegie Library on Fire, 4am:

It was approaching 4am when it was discovered that the work of destruction continued. At that time the City Hall and Carnegie Library became ablaze. Both of these buildings were gutted, only the walls left standing. The upper portion of City Hall including the clock tower fell in. Such was the intensity of the fires the firemen were driven out of the buildings.

A Devastating Sunday Morning, 8am:

As dawn broke on Sunday morning, 12 December, residents of Cork were then able to see the picture of Saturday night’s work of devastation. Fine buildings, with highly valuable stock, had been wiped out, and thousands of people were to become unemployed.

In one twenty-four period, over four acres of Cork City’s Centre had been reduced to ruins – 2,000 people had lost their jobs, and an estimated three million pounds of damage had been inflicted on Cork’s City Centre building stock. Nearly one hundred businesses and homes had been destroyed or badly damaged by fire and looting.

Streets of Destruction:

Throughout Sunday 12 December 1920, many willing helpers rendered assistance to the firemen in their challenging duties as fires smouldered after the Burning of Cork the previous night. Streets ran with sooty water, strewn with broken glass, and strong smell of burning. Dublin Fire Brigade with the assistance of firemen from Limerick and Waterford helped Cork Brigade.

A Recovery Operation Starts:

On Monday morning, 13 December, the work of clearing away the debris in the widely devastated area was commenced. To keep the public back, rope chains were placed around many streets and their ruined and wrecked buildings. Considerable progress was made as immense quantities of debris were cleared. Representatives from numerous builders’ firms were busily engaged inspecting the ruined premises in the flat of the city and with difficulty trying to save important books and documents from safes. At the gutted City Hall and at the Carnegie Library, it was possible to recover some documents, which were kept in strong safes within the buildings.

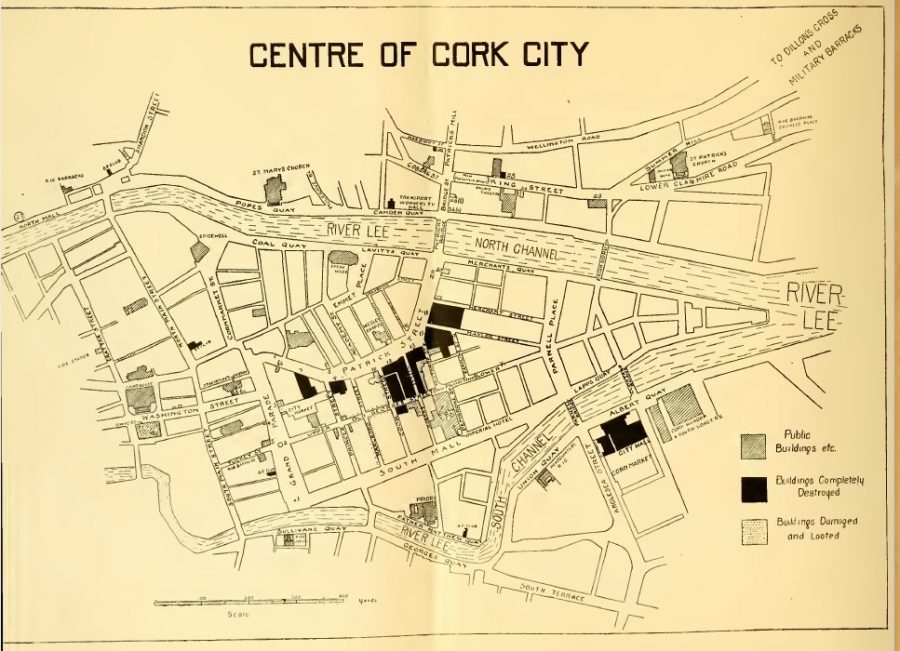

The Surveys of the City Engineer:

On being interviewed by the Cork Examiner, Cork Corporation Engineer Mr Joseph F Delany had already completed a hurried survey. Five acres of property had been destroyed. The St Patrick’s Street business premises from Merchant Street to Cook Street were all gone; the eastern side of the northern section of Cook Street had been demolished, while establishments in Oliver Plunkett Street, Winthrop Street, Morgan Street, Merchant Street, Maylor Street, and Caroline Street were wiped out – in addition to the extensive drapery establishment of Messrs Grant and Company situated between Princes Street and the corner of Grand Parade in St Patrick’s Street.

Debate in the House of Commons:

On Monday 13 December debate ensued in the House of Commons in Westminster, Independent MP and former member of the Irish Parliamentary Party Mr T P O’Connor asked for the particulars of the fires in Cork – “the number of buildings and the value of the property destroyed, the number of persons, if any, killed and wounded, whether the government had the discovered the authors of this series of crimes; whether any of them had been arrested, and whether the government would undertake to bring them to trial at the earliest moment”.

Sir Hamar Greenwood, Chief Secretary for Ireland, replied that he had not received a full or even a written report regarding the occurrences. To opposition jeering, he denied knowing who started the fires and rejected the suggestion that the fires were started by the forces of the Crown and that such claims were being used to undermine Government policy in Ireland.

Greenwood argued that “every available policeman and soldier in Cork was turned out to assist and without their assistance the fire brigade could not have got through the crowds and did the work they tried to do”. His contention was that the forces of the Crown had saved Cork from absolute destruction and that the whole event was orchestrated by Sinn Féin. He further related that there were “no incendiary bombs in the possession of the forces of the Crown in Ireland and there are incendiary bombs in the possession of the Sinn Féiners and we are seizing them every week”.

Rejection by Cork Corporation:

Back in Cork political reaction to Greenwood’s side stepping of responsibility saw full scale anger. The Lord Mayor of Cork, Donal Óg O’Callaghan and Corporation members sent a message to leading MPs rejecting Greenwood’s suggestion that Cork City was burned by any section of the citizen’s and demanding an impartial inquiry.

The Strickland Report:

The immediate follow up at Westminster was the creation of the Court of Enquiry, which was organised between 16-21 December 1920, by Major-General Sir E P Strickland, Commander of the British Sixth Division at Cork. Testimony was taken from 38 witnesses, including thirteen military, eleven police, and nine civilians. A number of Irish civil leaders declined to take part in the enquiry.

The Court stated there was circumstantial proof that K Company of the auxiliary division of the RIC and three members of the RIC were involved in the fire, which later broke out at the Cork City Hall. The remainder of the arson was credited to the fire having disseminated from the original outbreaks, and especially to the incompetence of the local fire brigade. The Enquiry failed to note that firemen had been prevented from controlling the burning by British forces who cut the hoses with bayonets and turned off the water at the hydrants.

While praising the military for its efficiency and discipline and, the Court recognised the outrageous activity of the police to the fact that a higher authority had sent to Ireland ill-disciplined and inexperienced men. The resulting report of the Court of Enquiry was widely referred to as The Strickland Report, though never officially published.

While the burning was admitted in report, for weeks afterwards Sir Hamar Greenwood, minimized it in Cabinet discussions. On 14 February 1921 the Cabinet decided to withhold the Strickland Report and not to establish any tribunal. The Cabinet did conclude that 50 men in K Company were seriously guilty of indiscipline, though they could not be individually identified. The Ministers also decided that the company should be broken up, and its commander suspended.

IRA Who Burnt Cork City Report:

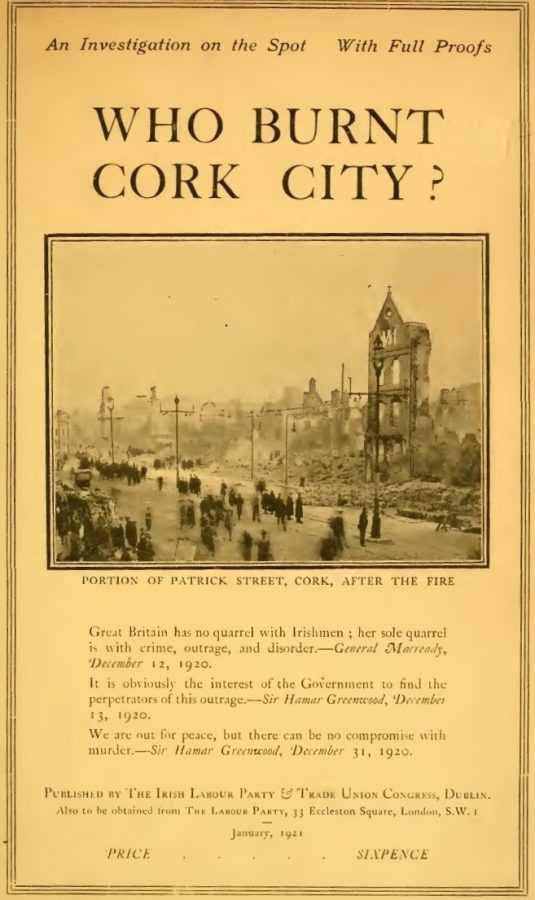

Meanwhile in Cork, in the absence of an immediate official report, Seamus Fitzgerald, Cork IRA Brigade No.1 penned Who Burnt Cork City. In Seamus’s witness statement in Bureau of Military History (WS1737),he notes that the great majority of the depositions contained in the pamphlet “Who Burnt Cork City” were obtained by him while Cork was still burning.

Seamus conferred at length in the preparation of the pamphlet with its editor, Professor and Sinn Féin Cllr Alfred O’Rahilly, who wrote the foreword to same. Every witness statement had to be sworn, and in no case did any witness refuse, despite the danger attached to same. The pamphlet had to be prepared quickly and published before Hamar Greenwood would make his promised speech in the British House of Commons absolving the British Forces. It was felt that the pamphlet would obviously suffer if published under the aegis of Dáil Éireann or Sinn Féin. It was arranged, therefore, to publish it under the name of the Irish Labour Party with a connection to the English Labour Party.

Title Page of Who Burnt Cork City, 1921, (source: Cork City Library)

Inside Title Page of Who Burnt Cork City, 1921, (source: Cork City Library)

Read more and Explore more, 9a. Cork’s Early Twentieth Century Story & Suburban Expansion | Cork Heritage